Research Article

Special Section: Circa Missiones. Jesuit Understandings of Mission through the Centuries

Questioning the Strategies Used to Create the Chữ Quốc Ngữ Romanized Script (1615–59)

Đặng, Kim-Bảo. “Questioning the Strategies Used to Create the Chữ Quốc Ngữ Romanized Script (1615–59).” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., 1, no. 2 (2025): 313–33. https://doi.org/10.51238/9x7ys9Z.

In the seventeenth century, Jesuit missionaries in Vietnam played a pivotal role in developing Chữ Quốc Ngữ, the Romanized Vietnamese script. Initially devised as a linguistic aid for evangelization, Chữ Quốc Ngữ evolved into a systematic orthography, ultimately becoming Vietnam’s official script. This study examines how Jesuits, particularly Portuguese and French missionaries like Alexandre de Rhodes, adapted their linguistic strategies from Chinese and Japanese missions to transcribe Vietnamese into Latin script. It explores their role in education, translation, and cultural accommodation, highlighting debates over terminology and orthographic standardization. By tracing the script’s formation through Jesuit dictionaries, catechisms, and educational materials, this study situates Chữ Quốc Ngữ within broader global Jesuit linguistic and pedagogical innovations.

Keywords:

missionary linguistics, Jesuit lexicography, Chữ Quốc Ngữ development, Romanization of Vietnamese

Vietnamese people may be surprised that when we spell out our name, for example Đ-ặ-n-g, most native Portuguese speakers can pronounce the name correctly without any prior instruction. The reason for this is the small yet significant historical connection between the Portuguese and the Vietnamese. In the seventeenth century, the Portuguese came to the kingdom of Annam (today’s Vietnam) as traders and missionaries. What they left behind was a new system of writing, changing the Annamese script from square ideographic characters to an alphabet (A, B, C). The Portuguese can thus read Vietnamese words.

This paper delves into the period from 1615 to 1659, during which the Romanized script, Chữ Quốc Ngữ, initially used as a source of transcription, was refined and synthesized into a systematic orthography.

Historical Context

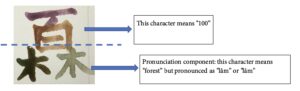

Soon after stepping foot on Cochinchina in 1615, the Jesuits learned that the Cochinchinese used Chinese for bureaucracy and as the language of the court. Chinese was the equivalent of Latin to them, and the men in the country spent years mastering the language in order to become a member of the literati who worked for the emperor. Chinese was called chữ Hán, “Chinese from the Han dynasty,” or chữ Nho, “the language of the Confucian literati.” However, the language of the common people was not Chinese. This modo de falar, or spoken language, had its own script, chữ Nôm, which was created by borrowing Chinese characters. At first, two Chinese characters were borrowed as two components of one new Nôm character. One component indicates the meaning, and the other suggests how the word sounds. Figure 1 provides an example—the Nôm word for trăm, meaning one hundred, in a Nôm character.

Figure 1. Nôm character for trăm.

Chữ Hán and chữ Nôm look alike but are not the same.[1] They were used in two different realms of literature. While Nôm, the spoken language, had its own literature, it remained the vulgar language of the people. It was akin to using Google Translate for the Chinese classics. Nôm was also used to compose poetry about daily life. When not preparing royal proclamations and edicts, Emperor Lê THánh Tông (1442–97) would use Nôm to describe nature and his feelings toward it, while Annamese women learned Nôm to compose poems about their everyday struggles. Therefore, while Hán, or Chinese, was used in legislation and to make the elites sound elegant, Nôm was used to express ordinary Annamese people’s everyday feelings. Hán thus had a similar status to Latin for the Europeans, while Nôm was akin to pre-modern European languages, such as Italian, Spanish, or Portuguese.

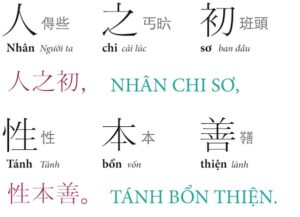

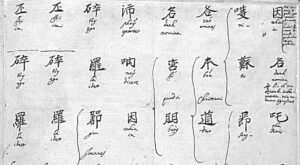

Nevertheless, Hán and Nôm were almost twins because of “Sino-Vietnamese,” which can be two things: Sino-Vietnamese sounds or Sino-Vietnamese words.[2] During this period, a native Annamese might see a Chinese character and read it in a Cochinchinese or Tongkinese dialect, which would make a Sino-Vietnamese sound. On the other hand, Chinese words conveniently made their way into the Vietnamese vocabulary and became Sino-Vietnamese words. These words had Chinese origins but followed the grammatical rules of Vietnamese. We can see this in classic books with Nôm explanations, which borrowed several Chinese characters in their entirety. For example, 本—which in Sino-Vietnamese should be bổn or bản, as in the name of Japan: Nhật Bản 日本—would be “vốn” in Nôm, meaning “original/originally” or “the capital money.” Below is an example of the first sentence in Tam Tự Kinh (三字經 in Chinese), the “Three Character Classic,” which was also taught in traditional Confucian schools in Vietnam (see fig. 2). The smaller characters are Nôm and served as a “Google translation” for the Hán entry. We can see that 本 is used in both the Hán and Nôm entries.

Figure 2. First sentence of the Three Character Classic.

Now We Can Get onto the Battle Plan . . .

We could imagine the dismay a Jesuit priest who was assigned to the Vietnamese mission felt upon learning that, in this kingdom, there were not only two commonly used languages but that these languages were essentially twins. What would their battle plan be to accommodate this kingdom’s culture and bring more souls to the Kingdom of Heaven? Unsurprisingly, the Jesuits enthusiastically tried many strategies for translating Christian texts to the Hán and Nôm languages.

First, they took advantage of the Sino-Vietnamese elements to introduce terms that had already been coined by the Jesuits in China. For example, the name of God in Chinese, Tientichu, which survived stringent debates between Jesuits in China and Japan, was deemed appropriate for use in Vietnam. In a letter dated 1631 from Visitor André Palmeiro to the superior of Tongkin, Gaspar do Amaral, Palmeiro accepted the use of Tientichu but not Shamty or Shangdi when referring to the Christian God. Tientichu became Thiên Địa Chủ, using the same Chinese Hán characters but now sporting Vietnamese pronunciation. Terms such as heaven, angels, and spirits were thus rendered as thiên đàng, thiên thần, and linh hồn. In fact, a report on the form of baptism in the Annamese language in 1645 revealed that linh hồn (alma spiritual) was introduced by the Jesuits to replace an existing term in order to remove the connotations of superstitious belief in ba hồn bải vía (translated by Portuguese Jesuits in the seventeenth century as “tres folegos e sete spiritos vitais,” or “three souls and seven spirits”).

However, in the same report of 1645,[3] there was a dispute over whether the term in nomine should be “nhân danh.” Here, “nhân danh” could be Sino-Vietnamese, yet Father Alexandre de Rhodes disagreed. “Nhân danh” could not be the Vietnamese translation for in nomine in “Ego Baptizo te in nomine Patris et Fily et Spirito Santo” (I baptize you in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit). Rhodes genuinely believed that “nhân danh” were two Chinese characters, which were transcribed into Romanization as “nhân danh,” using the Tongkinese dialect. However, this did not entirely follow Vietnamese grammatical rules. The term “nhân danh” was coined by the Jesuits from the Chinese mission. Rhodes also pointed out that “danh” (supposedly nomine) would become plural (nominibus), which would incorrectly represent the single embodiment of the Holy Trinity. He asserted that “danh” should be singular, so that Father, Son, and Holy Spirit were all equally one and important, rather than making nomine plural, which would mean that the rest would also have to be plural.

Rhodes also wanted the term for in nomine to be in the vernacular, or proprio modo de falar da terra[4] (i.e., the spoken language, Nôm), because then it would accord with the rest of the baptism form, which was also in Nôm. “Nhân danh,” in short, was borrowed from Chinese and created ambiguity in the meaning of the Holy Trinity. Rhodes thus proposed an alternative: “Tau lấy tên.” This was the propio modo de falar da terra, which he created by referring to the vernacular Nôm language to choose a more appropriate, approachable name for the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

The other Jesuits, five of which were peritus lingoa, or language masters, disagreed with Rhodes. They asserted that “nhân danh” could remain Chinese (or Hán) and be exempt from Chinese and Annamese grammatical rules. The baptism form would be a mixture of Chinese Hán and Vietnamese Nôm, in which Chinese Hán was as elegant and formal as Latin and Nôm as vernacular as Italian or Portuguese. And even though “nhân danh” was not Nôm, “nhân danh” would be introduced in the same way as they replaced “ba hồn bải vía” for “linh hồn.” We can see here how seriously the Jesuits took language translation—even though they could copy from the Chinese mission, they refused to do so entirely.

If the Jesuits involved in the form of baptism chose Nôm as the main language for Christian translation and discussed the terms that might be Sino-Vietnamese, Father Geronimo Maiorica took Nôm to another level. He decided to cooperate with the Annamese natives to compose an impressive collection of Christian stories in Nôm, both in language and script. Rhodes had some knowledge of the Nôm ideographic characters but chose to make translating his doctrine easier by Romanizing the Nôm language. Thus his “Phép giảng tám ngày” (Eight-day catechism)[5] was only printed in the Romanized Nôm script. Likewise, his fellow Jesuits Amaral and Antonio Barbosa must also have created dictionaries of Vietnamese and Portuguese using the Romanized script. Although these original manuscripts are lost, Rhodes credited these works as the sources for his Vietnamese–Portuguese–Latin dictionary. Nôm had a new script, appearing in the Latin alphabet thanks to the Jesuits. Nôm was also preserved in its original, ideographic form thanks to Maiorica and his Vietnamese assistants.

The Birth of Chữ Quốc Ngữ: From A to B

As he was alone in this journey, continuing with the Nôm script must have posed some challenges to Maiorica. Other Jesuits like Rhodes had used the Latin alphabet for Vietnamese words, in their personal correspondence, and in some translated Christian projects to make them more palatable to a European audience. The Annamese later chose this Romanized transcription over the Nômscript and named it Chữ Quốc Ngữ, meaning the national (and official) script.

However, Chữ Quốc Ngữ needed a lot of time to marinate as part of a process in which several transcription styles were combined, eventually merging into one synthesized orthography. And the birth of the national script culminated in the orthography being used to record philosophy, poetry, and ideology.

The process began with the Jesuits needing to mention the names of local people and places in their annual reports and letters. In early reports, we can already identify some Romanized transcriptions of Annamese words for the warlord “Chúa,” the emperor “bua,” and the mandarin “ou nghè” (the modern transcription has changed slightly to “ông Nghè”), or places such as “Thinh Hoa” (nowadays Thanh Hoá province) and “Nghean” (Nghệ An province). At the same time, the Jesuits were also translating Christian terms and simple sentences into the local languages. From Cristoforo Borri’s Relatione of Cochinchina,[6] we learn that the first sentence the Jesuits used to ask people seeking to convert to Christianity was “Con gnoo muon bau tlom laom Hoalaom[7] chiam” (“Con nhỏ muốn vào trong lòng Hoa Lang chăng?”[8] in modern spelling). However, at some point Father Francesco Buzomi (1576–1639), the superior of the mission, saw a comical play performed by the locals. In the play, the actor playing Buzomi would repeat the sentence “Con gnoo muon bau tlom laom Hoalaom chiam?” to children. If the children said “yes,” then they would pretend to jump into Buzomi’s belly and be reborn as Portuguese. It turns out that “Con gnoo muon bau tlom laom Hoalaom chiam” means “Do you want to reborn as a Portuguese?” Buzomi realized his error and quickly adapted, using a new sentence, “Muon bau dau christiam chiam” (“Muốn vào đạo Chritian chăng”), which translates literally as “Do you want to join Christianity?”

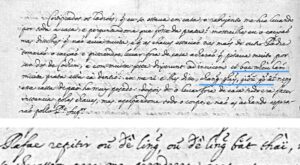

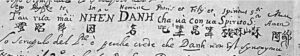

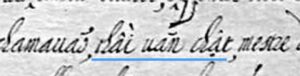

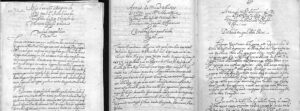

Soon thereafter, the Jesuit Francisco de Pina (1585–1625) became the first Portuguese Jesuit to achieve fluency in an Annamese tongue. In a letter dated around 1622–23, he revealed he had translated a treatise of classical Vietnamese literature for the purpose of learning the language.[9] Some scholars believe that this treatise must have been written in the Romanized script. Pina later taught Annamese to Rhodes, António de Fontes, and Amaral. Any teacher would have used textbooks, so he must have passed on his Romanized orthographical style to his students. Therefore, the Romanized orthography of these Jesuits was more or less identical save for the similarities indicating that it must have come from the same source, that is, Father Pina. This orthography can be called the Portuguese orthography for the Annamese language since it bears much of the Portuguese influence. Along the way, the Jesuits might also have needed to retell exactly what they had heard from local people, as we can see in a letter from Father Bernadino Reggio in 1632[10] recalling his capture by mandarins. He recounted that, while being arrested by the mandarin’s soldiers, he heard his followers shouting out for help: “Ông Đề Lĩnh bắt thài!,” meaning “the mandarin Lĩnh has captured the Master!” Other sentences he recorded were “có bạc nhiều lắm” (there is so much silver) and “chẳng phải giống gỗ ấy” (it is not that wood). An extract from Reggio’s letter to Visitor Palmeiro can be seen in figure 3.

Figure 3. Letter of Father Reggio; source: ARSI Jap. Sin. 80, fol. 62v.

However, this was not the only orthography used in the mission. The famous sentence “Con gnoo muon bau tlom laom Hoalaom chiam,” from Borri’s Relatione, was based on a different orthography. In this transcription, an Italian influence is evident, with the use of “gn” instead of “nh” for quốc ngữ “nhỏ.” Similarly, the Italian language was also used as the main reference for the Romanized transcripts in an epistola for Pater Noster in 1632.[11] This manuscript, which Visitor Palmeiro ordered to be drafted, consists of Latin Christian terms translated into Japanese, Chinese, and then Annamese. While the Chinese entry consists of both Chinese characters and Romanized transcript, the Japanese and Annamese entries only have the Romanized transcripts based on the Italian reference.

Perhaps here Palmeiro wanted to synthesize and improve the effectiveness of the lexicons for any Jesuits who had access to this material and could refer to their knowledge of Italian for precise pronunciation. However, their efforts to achieve this goal bumped into some obstacles, as the Italian language could not cover all the sounds of languages like Chinese and Annamese. Thus, he had to note, the pronunciation should follow German or Belgian pronunciation rules for the “ph,” “kh,” and “th” transcribed morphemes. He also added that the tonal marks were inspired by Greek pronunciation. Here, we can see that the process of Romanizing Asian languages, such as Chinese, Vietnamese, and perhaps Japanese, could not be based solely on one European language, such as Italian or Portuguese.

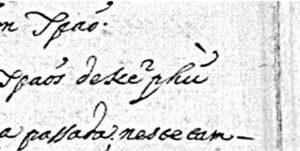

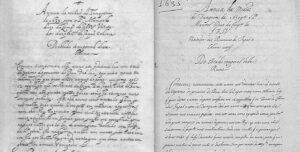

Borri’s Italian transcription and the one from the Pater Noster in 1632 did not evolve into a script, because to listen and then transcribe sounds is one thing, and to think and to write down one’s thoughts is another.[12] It was only in 1651, when Rhodes wrote his catechism completely in the Portuguese-based orthography, that the Romanized Vietnamese script was born. Or perhaps it can be considered to have been born later, in 1659, when the orthography was used by two native Annamese, Bento Thiện and Ignacio Văn Tín, to write a report[13] to Father Superior Filipo Marino.[14]

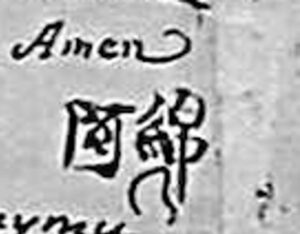

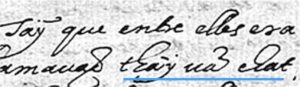

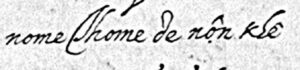

How, then, did the Jesuits create Chữ Quốc Ngữ, the Romanized script? We can assume that the Jesuits came to Cochinchina and Tongkin, listened to the language, and started transcribing it. However, the Jesuits also learned about the existence of Nôm script. Learning from the Jesuit experience in China and Japan, some of the peritus lingoa, language experts from the Society of Jesus, must have spent some time and effort to learn Nôm characters. Thus, Maiorica would not have been the only Nôm expert in the Society. In fact, in his letter to the superior general via the assistant of Italy, Marino documented the form of baptism in both the Romanized script and Nôm script. Interestingly, this letter has two copies[15]—one original and one assumed to be a duplicate—and in the Nômentries there are two variations of Nôm characters for “amen” (see fig. 4). The handwriting was also different, so Marino must have written one of the letters, and another Jesuit must have been asked to duplicate it for Marino. And since this Jesuit knew Nôm, he appears to have chosen different characters for “amen.” Similarly, in an anonymous letter responding to Father Sebastian de Amaya[16] on the form of baptism in Annamese, testimony from local Christians was included, and this testimony was written in the Nôm script. Thus, the presence of the Nôm script and the Jesuits who learned Nôm forces us to ask: Did the Jesuits also learn Nômcharacters and then rewrite them as Romanized words?

Figure 4. Extracts of Nôm characters for “amen” in a letter by Father Marino, from ARSI Jap. Sin. 80, fol. 86v (first) and ARSI Jap. Sin. 80, fol. 96 (second).

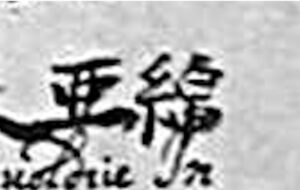

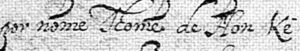

These two documents can help us better understand the influence of the Nôm script on the Romanized script. Sometimes, Nômcharacters were smaller, which indicates that it served as translation marginalia, like in a letter from Marino (see fig. 5). At other times, like in the testimony from Annamese people, the Romanized words look more like a side note (see fig. 6). The latter case seems more like the answer to our question: perhaps the Jesuit who knew Nôm wrote the Nôm entry and then later transcribed the text into romanization. Or perhaps a native Annamese documented the Nôm characters and one of the European Jesuits later transcribed it. This means the Romanized entry was created by someone reading the Nôm characters. In the first case, Marino might have referred to the Nôm characters to create his Romanized sentence. Regardless, in both cases Nôm characters could have been involved in the process of making Chữ Quốc Ngữ, the Romanized script. However, the creation of Chữ Quốc Ngữ can be attributed to the process of transcription over time through correspondence and the act of duplicating letters.

Figure 5. Extract from Father Marino’s letter; ARSI Jap. Sin. 80, fol. 86v.

Figure 6. Extract from “Circa forma baptismi Annamico idiomate prolatam” (1648); ARSI Jap. Sin. 80, fol. 79.

My Transcript Is Better than Yours

The Jesuits always made many duplicates of the same letter and sent them in different “via” and to different Jesuit residences. Since they are duplicates, they were supposed to be identical. However, I have found many duplicates of the same letter where the transcribed Vietnamese words are not exactly the same. In fact, what we witness here is an interaction between these duplicates, an interaction that improved the Romanization of the language.

Take the annual letter from Tongkin in 1632 as a case in point. The first duplicate is found in ARSI Jap. Sin. 85,[17] which Amaral seems to have reviewed, corrected with a side note, and finally signed. There is another duplicate of the 1632 annual letter in ARSI Jap. Sin. 88.[18] The handwriting looks different from the duplicate in ARSI 85 and seems closer to an annual letter from 1634,[19] which Amaral had been tasked with writing. Moreover, this duplicate does not have any corrections from a reviewer. This is more likely to be Amaral’s original annua of 1632.

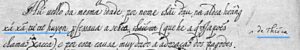

The first difference between these two duplicates is the use of “i” and “y” for the concluding morpheme. In the 1632 annual letter from ARSI 88, “y” was used. Similarly, in Rhodes’s dictionary, “y” is used mostly for the final sound. Nevertheless, in some letters written by Vietnamese lay brothers in 1659, “i” was used in place of “y.” So Amaral’s ARSI 88 (assuming this is his original letter) has “thay phu thuy” (fol. 126v), and the Vietnamese natives wrote thầi.[20] In modern spelling, “thầi” is not considered standard spelling, with the better one being “thầy.” Thus, Amaral’s spelling is closer to the modern spelling than the spelling of some the Vietnamese catechists, even though their letters were dated later than 1632. On the other hand, the other version of annua 1632 in ARSI 85 uses “i” for “thầi phù thủi” (fol. 139) and Kẻ đái (fol. 138). As Amaral uses “y” in annua 1634, this suggests that he did not duplicate the annua himself and had someone else do it. He sometimes had to review and correct the letter. If so, this letter in ARSI 8 should be a copy, and it followed the tendency of documenting the ending with “i” rather “y.” Extracts of ARSI Jap. Sin. 85 and ARSI Jap. Sin. 88, for the same name of a person, thầy văn chật, can be seen in figure 7.

Figure 7. Annua 1632; ARSI Jap. Sin. 85 (first); ARSI 88 (second).

Both annua also documented some unsettling rules of spelling, such as spelling “/ʈ/” as “tl” or “tr.” We can see the Jesuits wrote “Đàng Trong” and “Đàng Trên” (which are the modern spellings) as “đàng tlaõ” (ARSI 85 fol. 125) and “đàng tlên” but then wrote “chúa triết” (ARSI 85 130) and “thịnh tràng” (ARSI 85 167) (which are exactly the same as the modern spellings). The examples also present the spelling for the ending sound “/ŋ/” as either ng (“đàng”) or õ (“tlaõ”). Moreover, “/ŋ/” can also be written as “ũ” as in “oũ tlui” (ARSI 85 fol. 125v) (“ông trui” in modern spelling). Interestingly, modern Portuguese spelling sometimes transcribes the sound of the Zen Buddhist bell “dong” as “dlão,”[21] which seems to follow the same logic as writing Đức Long (a Vietnamese emperor) back then as Đức Laõ. Fast-forward to the modern day, and the rules are now settled, as “/ʈ/” is written as “tr” and “/ŋ/” as “ng.” A critical question to ask here is whether these spellings were simply the variations of a sound that had been settled as one rule or existed back then as different sounds and hence different spellings. To try to answer this question, we could consult Rhodes’s dictionary Việt Bồ La (1651). For the entry on “trứng” (ovo-egg), Rhodes documented two spellings: “trấng” and “tlứng.” Thus it seems like “tl” and “tr” are just variations of the spelling for “/ʈ/.” For a final “/ŋ/” sound, Rhodes separately documented the entry for “oũ,” as in “oũ” (avo or senhor) or “đức oũ” (translated by the Jesuits from “excelentissimo senhor,” equivalent to “your highness” in English), and he also documented “dentro” in another entry, meaning inside, as either “trũ” or “tlão” (the modern spelling would be “trong”). Here, it is hard to tell if he means the ending “/ŋ/” sound can be spelled as either “ũ/õ” or “ng” or not.

Nevertheless, compared to the one from ARSI 88, the spelling from annua 1632 in ARSI 85 is a better spelling, with more diacritical marks (see again fig. 7). Take these entries below, for example. Figure 8 is from ARSI Jap. Sin. 85, annua 1632. As discussed earlier, there is the hallmark of using letter “i” for “thầi đạu,” while in figure 9 “y” was used. Then, the name of a location was documented. In ARSI Jap. Sin. 85, village (aldea) was written as “hoằng xá xã,” and two diacritical marks were used to indicate the different pronunciations for “á” and “ã.” Meanwhile, in ARSI Jap. Sin. 88, the same name was written, but with the simpler, or primitive, “xá xá” (see fig. 9). Let’s assume that Amaral wrote the Jap. Sin. 88 annua 1632 and revised Jap. Sin. 85 (because, as we can see, someone corrected the word “thícca Budha” on the side and the handwriting is similar to the one in Jap. Sin. 85). That means ARSI Jap. Sin. 88 was written first and Jap. Sin. 85 is a duplicate. Here, we can see that Amaral did not correct “xá xã” as “xá xá” to make them identical. He only corrected “Thíc ca.” It thus stands to reason that Amaral believed that “xá xã” makes sense or was more accurate, so he decided to leave it as it was. The same goes with “hoằng” in place of the original “hoang.” This juxtaposition here sparked an exchange between the author and the Jesuit who duplicated the letter. In other words, there was communication between these two transcribers to make the transcription of Vietnamese words more accurate.

This is how we can picture the scene: the person who duplicated the letter did not blindly copy the letter. In fact, he had some knowledge of the Vietnamese language and his own idea of how it should be transcribed, preferring to use “i” instead of “y.” He heard how people said the name of the village and must have thought: How about I use “á” and “ã” for “xá xã”? Same with “hoằng” and “tư tư.” However, he respected “uyen” for “huyện” and did not change the final character. Amaral then revised the letter and corrected it when necessary (“Thíc ca”).

That is one scenario, when there were two people, Amaral and the person who was assigned to copy annua 1632. Another scenario would be that Amaral wrote both letters but had a change of heart while rereading the first and decided to fix some of the transcriptions of Vietnamese words. This meant he first wrote the letter found in ARSI 88 and then made another copy, which was the letter in ARSI 85. This would be a more logical explanation for the evolution of the transcript, from “xá xá” to “xá xã.” However, what does not fit the logic here is Amaral’s constant side notes, correcting some details of the letter and even the transcribed Vietnamese words. Why did he not do the same with the letter in ARSI 88 and just this particular ARSI 85? Moreover, if the transcription was evolving here, does this mean there was a gap between Amaral writing the letters? If that were the case, it also shows that Amaral quickly changed his transcription within just a year, as an annua was supposed to be a report of a single year.

Figure 8. ARSI Jap. Sin. 85.

Figure 9. ARSI Jap. Sin. 88.

The annual report in 1632 and its duplicate are not the only outstanding case. In the annual report of 1635 from Father Fontes, we again see an interaction within the duplicate letters. Take a look at figures 10 and 11 for ARSI 85 (top) and ARSI 88 (bottom) for the same entry—“phũ.”

Figure 10. ARSI Jap. Sin. 85a1 fol. 9v.

Figure 11. ARSI Jap. Sin. 88 fol. 244v.

As can be seen, the transcriber from ARSI 88 has already adopted the “~” diacritical mark (called ngã in Vietnamese) for the word, whereas “phũ” in ARSI 85a has two marks, huyền and hỏi. These two marks cannot coexist in the modern spelling of Chữ Quốc Ngữ. However, interestingly enough, to teach foreigners to pronounce “ngã,” some teachers would tell them to think of the huyền and hỏi marks, then pronounce those two marks followingly. So, quickly saying “ù” then “ủ” would make it sound like “ũ.” Did the transcriber of ARSI 85a have the same idea? However, the “ngã” diacritical mark is still found in ARSI 85a in several entries such as “lĩnh” (“ou đề lĩnh,” fol. 11) and “bẫi” (fol. 12v). For the entry “bẫi,” ARSI 88 on the contrary has both huyền and hỏi. Perhaps the conclusion here is that two ways existed to mark the tone ngã back then, either with a two-mark huyền-hỏi or only with ngã.

Moreover, both versions of Fontes’s annua of 1635 have side notes, corrections, and explanations in what appears to be a different hand. So, in total we can see that there are three different handwritings for annua 1635, and the side notes’ handwriting seems to match that of annua 1631, also signed by Fontes. Words are transcribed that bear no similarities and could be read as totally different information, but the reviewer—the one who made the corrections on the side—did not seem to mind.

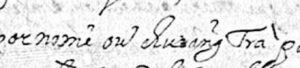

Figure 12. Extracts from two duplicates of the annual letter of 1635; ARSI Jap. Sin. 85a1, fol. 17v (first); ARSI Jap. Sin. 88, fol. 251 (second).

In the upper part of the extract in figure 12 (ARSI Jap. Sin. 85a1, fol. 17v), a person named Thome is described as being from Nộn Khê, but in the lower part (ARSI Jap. Sin. 88, fol. 251) he is described as being from Hon Ke. These transcripts do not render or bear the same sound. The consonant N does not sound the same as the consonant H.

Here is what is interesting: there are at least five versions of annua 1635 in ARSI Jap. Sin. They are in ARSI Jap. Sin. 88, ARSI Jap. Sin. 85a 1, Jap. Sin. 85a 1a, Jap. Sin. 85a 1b, and Jap. Sin. 85a 1c. A comparison of these five versions helps reveal why “Nộn Khê” became “Hỏn Kè” (or vice versa). However, before returning to this issue, we should consider the possible timeline of how these letters were duplicated. One might have been made first without necessarily being the original. Why? Because none of the five handwritings match with annua 1631, which was written by Fontes. For starters, the letter from ARSI Jap. Sin. 85a 1a has extra paragraphs in the side note,[22] which never made its way to the other four versions. However, at the beginning of the letter, the narrative introduces the year of 1635 as “the seventh year of Bua Đức Long reign, or what would be năm hợi, year of the pig.” The letter from ARSI Jap. Sin. 85a 1 is missing the word năm (year). In two of the letters, in ARSI 85a1a (which has the extra paragraphs mentioned earlier) and ARSI 88, năm was added later and appears in a small upper space. In ARSI 85a 1b and 1c, năm was simply written in line with the other words. Later on, at the beginning of the “Estado Geral” section, the word europeos is in ARSI Jap. Sin. 85a1, whereas it is struck out from the other four letters: “Cultivamos esta christandade tres padres europeos.” Three other letters, from ARSI 88, ARSI 85a1, and ARSI 85a1a, have some side notes that have become normal paragraphs (without the word europeos) in ARSI 85a1b and ARSI 85a1c. Therefore, it is safe to say that the letter that came first is either the letter from ARSI Jap. Sin. 85a1 (because the word năm has not been added, nor has the word europeos been struck out) or Jap. Sin. 85a1a (because it has more side notes). The order should therefore be Jap. Sin. 88 (because it still has side notes), followed later by Jap. Sin. 85a1b and 85a1c.

Thus, ARSI 85a1 and 85a1a came first with “Nộn Khê” (ARSI 85a1) and “Nôn Kê” (ARSI 85a1a and 85a1b). In ARSI Jap. 88 and ARSI Jap. Sin. 85a1c, “Nộn Khê/Nôn Kê” suddenly became “Hon Kè.” There thus appears to have been a transcription error while copying letters. Similarly, in ARSI Jap. Sin. 85a1, the entry “ông nghề quế” is “ou nghề quế” (fol. 15v), whereas in ARSI 85a1a it is “ou nghề koế” (fol. 16). “Quế” and “koế” look different but still indicate the same sound. Nevertheless, when “koế” became “kốc” (1b) and “koc” (88 and 1c), it would sound very different. Table 1 below summarizes some variations in the five duplicates of annua 1635.

Table 1. Some of the differences between the five duplicates of annua 1635

There thus seems to have been some form of interaction, or communication, between the person who wrote or duplicated ARSI Jap. Sin. 85a1 and Jap. Sin. 85a1a—whether or not they duplicated from the same original letter or copied each another—to improve the transcribed Vietnamese words. They each have their own sense of how Vietnamese words sound and present these words differently—“quế” versus “koế” and “Khê” versus “Kê.” In fact, both letters have more diacritical marks than the rest, especially subtle marks such as “ư” and “ơ” in “Bua đức lou” and (“năm”) Hợy. Moreover, the person who wrote ARSI Jap. Sin. 85a1 even used “ơ” for the diphthong “ươ,” which made its way into modern spelling. To write “argue,” the person from ARSI 85a1a used “ua” (and it seems as though he struck “ơ’” and replaced it with “a” instead). “Ua” also made its way to the spelling used in Rhodes’s dictionary in 1651 (see fig. 13):

Figure 13. Extracts from ARSI 85a1a (first) and ARSI 85a 1 (second) for the mention of a person called ông Chưởng Trà.

Unfortunately, I was unable to identify the same interaction or communication in the rest of the duplicated versions for “ôngChưởng Trà” and other transcribed words. It seems that whoever copied the original annua, or its duplicate, got it very wrong in ARSI 88, ARSI 85a1b and c, making it appear as though they had not heard of the location “Nộn Khê” nor the person “ông nghề quế,” and that they did not know how the Vietnamese language sounds. Moreover, unlike in the other version, the person who copied the annua from ARSI 85a1c did not bother adding any diacritical marks. Interestingly enough, the letter in ARSI 88 was sent first, as indicated by “1a via.” Annua 1635, in ARSI 88, has the clearest handwriting, and with some side notes when clarifications were needed.

What cannot be observed in the five duplicates of annua 1635 is the interaction between the person who copied the letter and the reviewer. At least it is not visible, as for example when “thíc ca” was corrected in annua 1632. The person who reviewed them must have agreed with both “ou nghề quế” and “ou nghề koế” and did not make any correction. However, the reviewer did not correct “kốc” or “koc” even though they are wrong. The same applies with the typo “Hon Ke” for “Nộn Khê.” Thus, as Fontes was known to be skilled at Vietnamese, it is doubtful that he reviewed the duplicates. In the case of annua 1632, Amaral seems to have reviewed the copy very carefully, leaving transcribed words that were different but perhaps made sense and corrected them when necessary. And consequently, he might have adopted some transcribing ideas from the 1632 annua and applied them to annua 1634 (in the case of the final “i” sound in “thầi” and “thầy”). However, we should not conclude that there was no interaction between the person who duplicated the letter and the person who reviewed it. It might simply be invisible. It is impossible to know for sure if the reviewer, or Father Fontes, was not aware of the different transcriptions. After all, the annual reports were sent to report on life in the mission rather than being entries in a long-distance spelling bee.

Finally, I want to end this paper by attempting to identify the Jesuit who duplicated the annual letter in 1632 for Father Amaral. Father Regio’s handwriting would match the duplication (see figs. 3, 4, and 5 for comparison). Regio[23] also demonstrated his progress in Romanizing Vietnamese sentences in a personal letter to Palmeiro. His Romanized “ông Đề Lĩnh bắt thầy,” “có bạc nhiều lắm,” and “chẳng phải giống gỗ ấy” all have very clear diacritical marks. The letter shows that his understanding of the Vietnamese language was very advanced (because he captured complete and complex Vietnamese sentences). Indeed, Amaral spoke highly of him and his efforts to advance in the language,[24] and in 1634 Fathers Amaral, Fontes, and Regio prepared manuscripts in the Vietnamese language using a huge range of vocabulary. Regio was also very enthusiastic about possessing books in Vietnamese as a language reference and taught some boys how to read and write, presumedly in Portuguese, which Father Amaral considered a great help. Thus, as Father Regio was with Father Amaral in 1632, he must have been assigned to duplicate the annua and interacted with Amaral within the letter about how he would Romanize words.

Figure 14. Duplicates of annua 1635. From left to right: ARSI Jap. Sin. 88; 85a1; 85a1a; 85a1b; 85a1c.

Table 2. Some variations of the Romanized styles from the five duplicates of annua 1635

Notes:

[1] My understanding of this topic is based on the work of Quang-Hồng Nguyễn and John D. Phan. For Quang-Hồng Nguyễn, see Khái Luận Văn tự học chữ Nôm [Introduction to Nôm study] (Hanoi: Nhà Xuất bản Giáo Dục, 2008); and for John D. Phan, see John D. Phan, “Rebooting the Vernacular in Seventeenth-Century Vietnam,” in Rethinking East Asian Languages, Vernaculars, and Literacies, 1000–1919, ed. Benjamin A. Elman (Leiden: Brill, 2014), 96–128.

[2] For an understanding of Sino-Vietnamese, see Xuân-Hạo Cao, Tiếng Việt Văn Việt Người Việt (Ho Chi Minh City: Nhà Xuất Bản Trẻ, 2017), and Ngọc Phan, Mẹo giải nghĩa từ Hán Việt và chữa lỗi chính tả (Hanoi: Nhà xuất bản Thanh niên, 2000).

[3] “Manuscritto em que se prova que a forma do baptism pronunciada em lingoa Annamica he verdadeira,” ARSI Jap. Sin. 80, fols. 35–38.

[4] “Manuscritto em que se prova que a forma do baptism pronunciada em lingoa Annamica he verdadeira,” ARSI Jap. Sin. 80, fol. 35.

[5] Alexandre de Rhodes, Cathechismvs Pro IJS, qui volunt suscipere baptismvm in octo dies diuisus: Phép giảng tám ngày, Congregationis de Propaganda Fide in Lucem Editus (Rome: Typis sacræ Congregationis de propaganda fide, 1651).

[6] Christoforo Borri, Relatione della nuova missione Delli P.P. della Compagnia di Giesù al regno della Cocincina (Rome: Francesco Corbelletti, 1631).

[7] The term Hoa Lang was used by Vietnamese locals to refer to early Portuguese missionaries, though its origin remains debated. A popular theory suggests that Hoa Lang referred to a type of sweet potato flower, which resembled patterns on the missionaries’ garments. Roland Jacques, however, traces the term to the Chinese rendering of “Franks” (from Latin Franci), which was pronounced Pha-lang in Cantonese and allegedly adapted into Vietnamese as Hoa Lang. Vietnamese linguist and journalist An Chi challenges this interpretation, arguing that the phonetic transformation from Pha-lang to Hoa Lang is implausible. See Roland Jacques, “Nguồn gốc và ý nghĩa các tên gọi ‘Hoa Lang’ và ‘Hoa Lang đạo’” [The origin and meaning of the terms ‘Hoa Lang’ and ‘Hoa Lang đạo’], Ngôn ngữ 8 (2000); and An Chi, “Về bài liên quan đến hai tiếng ‘Hoa Lang’ của Roland Jacques” [Regarding the article about the two words ‘Hoa Lang’ by Roland Jacques], Kiến Thức Ngày Nay, no. 365 (October 1, 2000).

[8] Borri, Relatione della nuova missione, 135.

[9] For a deeper understanding of this letter from Father Pina, see Roland Jacques, Portuguese Pioneers of Vietnamese Linguistics: Prior to 1650(Bangkok: Orchid Press, 2002).

[10] Bernadino Reggio, 1632, ARSI Jap. Sin. 80, fols. 62–66.

[11] André Plameiro, “Pater Noster” (1632), ARSI Jap. Sin. 194, fols. 5–11v.

[12] I concur with the assertion made by Quang-Hồng Nguyễn regarding this argument in Khái Luận Văn tự học chữ Nôm, 98.

[13] ARSI Jap. Sin. 81 fols. 246–47v.

[14] This is just an estimated year because that was when the letter was dated. There might be letters written by natives before 1659.

[15] ARSI Jap. Sin. 80, fols. 85v–87 and ARSI Jap. Sin. 80, fols. 96–96v.

[16] “Circam formam baptismi Annamico idiomate prolatam,” 1648, ARSI Jap. Sin. 80, fols. 75v–81v.

[17] “Annua de reino de Annam do anno de 1632 pera o Padre Andre Palmeiro da Companhia de JESU visitador das provincias de Japam e China,” ARSI Jap. Sin. 85, fols. 125–74.

[18] “Annua de reino de Annam do anno de 1632 pera o Padre Andre Palmeiro da Companhia de JESU visitador das provincias de Japam e China,” ARSI Jap. Sin. 88, fols. 117–58v.

[19] “Annua de 1634 de reyno de Annam para o Padre Andre Palmeyro visitador das provincias de Japão e China,” ARSI Jap. Sin. 88, fols. 170–219.

[20] ARSI 81, fol. 246.

[21] I spotted this spelling by chance in a movie on Netflix with a Portuguese subtitle.

[22] Fol. 3v.

[23] The following is some of Regio’s biography as written by Father Amaral:

Father Bernardino Regio entered the Society of Jesus on November 21, 1612. He spent two years studying rhetoric, three years studying philosophy, and four years studying theology. Consistently, for fourteen years straight, he requested to be sent on mission to India, until finally the Father General granted his wish, and he embarked for India in 1628. However, he spent an additional year in Portugal before heading to Macau. In Macau, with the intention of going to Japan, he decided to learn the language. Eventually, the Father Superior [Amaral does not mention who or from which residence or college] sent him to Tongkin in 1631. He spent two years and seven months in Tongkin.

[24] ARSI Jap. Sin. 88, fols. 172–72v.

Borri, Christoforo. Relatione della nuova missione Delli P.P. della Compagnia di Giesù al regno della Cocincina. Rome: Francesco Corbelletti, 1631.

Cao, Xuân-Hạo. Tiếng Việt Văn Việt Người Việt. Ho Chi Minh City: Nhà Xuất Bản Trẻ, 2017.

Jacques, Roland. Portuguese Pioneers of Vietnamese Linguistics: Prior to 1650. Bangkok: Orchid Press, 2002.

Nguyễn, Quang-Hồng. Khái Luận Văn tự học chữ Nôm [Introduction to Nôm study]. Hanoi: Nhà Xuất bản Giáo Dục, 2008.

Ngọc, Phan. Mẹo giải nghĩa từ Hán Việt và chữa lỗi chính tả. Hanoi: Nhà xuất bản Thanh niên, 2000.

Phan, John D. “Rebooting the Vernacular in Seventeenth-Century Vietnam.” In Rethinking East Asian Languages, Vernaculars, and Literacies, 1000–1919, edited by Benjamin A. Elman, 96–128. Leiden: Brill, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004279278_005.

Rhodes, Alexandre de. Cathechismvs Pro IJS, qui volunt suscipere baptismvm in octo dies diuisus: Phép giảng tám ngày, Congregationis de Propaganda Fide in Lucem Editus. Rome: Typis sacræ Congregationis de propaganda fide, 1651.

- Title: Questioning the Strategies Used to Create the Chữ Quốc Ngữ Romanized Script (1615–59)

- Author: Kim-Bảo Đặng

- Article Type: Research Article

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.51238/9x7ys9Z

Language: English - Pages: 313–333

- Keywords: missionary linguistics; Jesuit lexicography; Chữ Quốc Ngữ development; Romanization of Vietnamese

- In: Jesuit Educational Quarterly

- In: 2nd ser., Volume 1, Issue 2

- Received: 29 July 2024

- Accepted: 05 August 2024

- Publication Date: 28 April 2025

Last Updated: 28 April 2025 - Publisher: Institute of Jesuit Sources

- Print ISSN: 2688-3872

- E-ISSN: 2688-3880

APA

Đặng, K.-B. (2025). Questioning the strategies used to create the Chữ Quốc Ngữ romanized script (1615–59). Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 1(2), 313–333. https://doi.org/10.51238/9x7ys9Z

CMOS

Đặng, Kim-Bảo. 2025. “Questioning the Strategies Used to Create the Chữ Quốc Ngữ Romanized Script (1615–59).” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., 1, no. 2: 313–333. https://doi.org/10.51238/9x7ys9Z.

MLA

Đặng, Kim-Bảo. “Questioning the Strategies Used to Create the Chữ Quốc Ngữ Romanized Script (1615–59).” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., vol. 1, no. 2, 2025, pp. 313–333. https://doi.org/10.51238/9x7ys9Z.

Turabian

Đặng, Kim-Bảo. 2025. “Questioning the Strategies Used to Create the Chữ Quốc Ngữ Romanized Script (1615–59).” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., 1, no. 2: 313–333. https://doi.org/10.51238/9x7ys9Z.

© Institute of Jesuit Sources, Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, All Rights Reserved