Research Article

Special Section: Circa Missiones. Jesuit Understandings of Mission through the Centuries

Joseph-Pierre de Bonnécamps: A Jesuit Scientist Living in Turbulent Times

Cunningham, John D., S.J. “Joseph-Pierre de Bonnécamps: A Jesuit Scientist Living in Turbulent Times.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., 1, no. 2 (2025): 273–93. https://doi.org/10.51238/38Z7fp6.

Joseph-Pierre de Bonnécamps, S.J. (1707–90), was a Jesuit scientist, educator, and hydrographer whose career intersected with key events in 18th-century French colonial history. Trained in mathematics and hydrography, he taught at the Jesuit College in Quebec (1744–59) and participated in the 1749 Céloron expedition, documenting geographic, botanical, and cultural observations in his journal. His meticulous measurements and maps contributed to French strategic efforts in North America. Following the fall of Quebec in 1759 and the suppression of the Jesuits in France, Bonnécamps returned to pastoral work, including a controversial assignment in Saint-Pierre. Ultimately, he spent his later years as a tutor and scientific observer in Brittany. His life offers insight into the roles Jesuits played as educators, scientists, and intermediaries between military, political, and Indigenous communities. This study reexamines Bonnécamps’s contributions, situating him within the broader scientific and geopolitical transformations of his time.

Keywords:

Jesuit science; hydrography, cartography, Quebec, Joseph-Pierre de Bonnécamps

Preface

On May 28, 1790, Joseph-Pierre de Bonnécamps died at the chateau of Tronjoly. His death announcement reads:

May 29, 1790, the interment in the church of Our Lady (of Gourin) of the Venerable Mister Joseph-Pierre de Bonnécamps, priest, previously a member of the Society of Jesus, originally from Vannes, died in Chateau de Tronjoly at the age of eighty-four [sic].[1]

Simple and concise, this succinct death notice does not reflect the rich experiences and complexity of a fascinating Jesuit priest and scientist living in the turbulent historical era of the eighteenth century.

Joseph-Pierre de Bonnécamps was born in 1707 in Vannes, France. He died there in 1790 at the age of eighty-two. A Jesuit for sixty-two of those eighty-two years, Bonnécamps’s lasting legacy was the journal he kept during his over five-month journey around the eastern Great Lakes, North America, in the summer and fall of 1749. Submitted on October 17, 1750 to Commandant General Roland-Michel Barrin de la Galissonière, the governor of Quebec, the document, readily accessible in English, has been extensively studied.

After the exploration, there are four other far less examined letters written by Bonnécamps that were presented at the end of the nineteenth century by a Canadian researcher: Auguste Gosselin. There are also various letters and documents written by others in the eighteenth century that refer to Bonnécamps and his life.

Bonnécamps was a Jesuit living through three major historical events: the French colonization of New France (Canada and the United States), the French and Indian War (1754–63)—a war between France and England to decide who would govern and control vast regions of the United States and Canada—and the suppression of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). All three of these events profoundly affected Bonnécamps’s life.

Jesuit Influence in the Colonization of New France

One of the major events to affect Bonnécamps’s life was the French colonization of North America. Although begun a century before Bonnécamps’s birth, the parameters of its existence would become a major part of his life.[2]

The first Jesuits to arrive in this region of North America did so in 1611, attempting to establish a mission in Acadia (present-day Nova Scotia and Maine). The mission failed due to English raiders, and the Jesuits would depart from there two years later. In 1625, the Jesuits would arrive on the banks of the St. Lawrence River. Once again the victims of English raiders, they would depart from there four years later. In 1632, the French reasserted their control of Quebec, with the Jesuits following shortly thereafter. The Jesuit College of Quebec was founded in 1635.[3] Battles with the English for control of this region would continue throughout the eighteenth century.

Not all Jesuits who left France bound for New France planned to be missionaries among the Indigenous peoples. Some of the Jesuits would remain permanently in cities, such as Quebec, to teach in colleges or preach in Jesuit churches. These Jesuits were sent to New France to assist in the spiritual formation of the French residents working there. Bonnécamps was missioned to New France to be a professor of hydrography at the College of Quebec in 1744.

Instruction in hydrography began in Quebec in 1651 at the expense of the French government. One such student at the Jesuit College in Quebec was Louis Joliet (Jolliet), who explored the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers with another Jesuit, Jacques Marquette, in 1673. Marquette drew up a map of North American rivers, A Map of the Discovery of the Mississippi, preceding Bonnécamps by over a century. From 1697 to 1700, Jolliet actually held the chair of hydrography in Quebec. After Jolliet’s death, another French layman, Jean-Baptiste Franquelin, was appointed as the new teacher of hydrography. Although he received the salary for the post, Franquelin never ventured from France to Canada to assume his responsibilities. At this point, the Jesuits, already present at the College of Quebec, were offered the position, accepting it and its stipend in 1709.

Hydrographic studies, during an era where voyages of discovery were a constant topic of discussion, were very popular among students. The precise surveying of a whole continent was essential for strategic defense. In response to both these interests, the French government in Quebec strongly supported youth in learning astronomy and mathematics, topics central to the accurate mapping of rivers and other water bodies. Bonnécamps is often given the title of the “last teacher of hydrography” at the Quebec College due to the fall of Quebec to the English in 1759.

Bonnécamps’s scientific research and teaching while residing in Quebec covered four major subjects: mathematics, astronomy, meteorology, and hydrography. The first three are intimately connected to the science of hydrography. Astronomy and meteorology were essential for recording accurate latitude and longitude readings, numbers necessary to produce a map; mathematics was important to interpret these measurements accurately.

The Jesuit Formation of Joseph-Pierre de Bonnécamps

Bonnécamps was born on September 5, 1707 to Nicolas de Bonnécamps and Anne Muerel. Nothing is recorded of his parents or childhood. He entered the novitiate of the Society of Jesus in Paris on November 3, 1727.[4] He was a little over twenty years old at that time. After two years of novitiate, Bonnécamps studied philosophy at the Jesuit College of La Fléche for three years (1729–32). After these studies, Bonnécamps spent his regency teaching grammar at Caen (1732–36) and then humanities and rhetoric to more senior students at Vannes (1736–39).

That he spent an unusually high number of years in regency (seven) raises the possibility that he was also studying science during this period, although this is not definitively clear from the sources. After his period of teaching humanities in France, it was noted that “his tastes and talents applied more toward mathematics; and since a teacher was needed to teach this science at the college of Quebec, it was decided that he would be sent there.”[5] But nothing is specifically mentioned of when these scientific studies occurred. As typical for Jesuits after regency, Bonnécamps then studied theology at the Collège Louis-le-Grand (1739–43).[6]

There is no record of the date of Bonnécamps’s ordination to the priesthood. Surprisingly, the French Jesuit catalogs, yearly listings of Jesuit manpower, their assignments, and locations, do not list this date. Some sources do list Bonnécamps’s ordination year as 1742 or 1743. Either of these years is a possibility since they were the concluding years of Bonnécamps’s theological studies. Until recently, many Jesuits had their priestly ordination at the end of the third year of theological studies. For Bonnécamps, this would have been 1742.

His scientific studies may have occurred during his theological studies since he apparently was ready to teach hydrography when he was sent to Quebec in 1744. As Bonnécamps arrived in Quebec in 1744, it is most likely that the undocumented year of 1743–44 was spent in France doing his tertianship, the third probation for a Jesuit.

Since the court of France provided for the teaching of hydrography in Canada, no surveyor was appointed in the colony unless he had a certificate as professor of hydrography. Bonnécamps would have needed this certificate if he were to teach in Quebec.

There is a discrepancy of just when Bonnécamps was sent to Quebec. One source states that “Father de Bonnécamps arrived in Quebec in the summer of 1741 and started immediately to teach the science of mathematics and hydrography for which he was sent to Canada.”[7] This assertion implies that Bonnécamps had already studied theology and had been ordained, but this contradicts the record of his theological studies in France (1739–43). Most documents point to 1744, and there is also no record of any activity by Bonnécamps in Quebec before 1744.

There is one major record of an event in the Jesuit formation of Bonnécamps: his final vows. It is recorded that he made final vows, including the fourth vow to be sent by the pope to the foreign missions, in the church of the Jesuits in Quebec on December 8, 1746. With these solemn vows, Bonnécamps would have been a “solemnly professed” Jesuit, a member of the order from which higher positions of authority, such as provincial, novice master, and rector, would have been chosen.

Bonnécamps’s Life in Quebec

The Jesuit mission to New France had various residences and missions. There were two residences, one each in Quebec and Montreal, serving the French residents in both cities. The Native American missions included the Huron mission of Detroit and the nearby Iroquois mission of Sault-St. Louis. Throughout the Great Lakes region were missions ministering to the Abenakis, Montagnais, and the Outaouais Indigenous peoples. There was also the distant mission of New Orleans, mainly serving the French residents there.

When Bonnécamps arrived at the College of Quebec in 1744, he would have joined a community of about twenty Jesuits, a figure similar to that recorded in the Jesuit catalog for the year 1749, the year of Bonnécamps’s hydrographic expedition.[8]

The most insightful piece of information about the lifestyle of these twenty Jesuits was offered by a visitor to the college on August 10, 1749,[9] when an “illustrious and learned Swedish” man, Peter Kalm, a scientist and diarist, recorded his interactions with the Jesuits resident in Bonnécamps’s house in Quebec:

The Jesuits are usually very educated and given to study, and at the same time polite and nice company. There is something pleasant in their entire demeanor, and it is not surprising that they captivate the mind of the people. They speak rarely of religious questions, but when they speak of them, they are very careful to avoid disagreement.[10]

Kalm continues with glowing praise for the Jesuits before eventually arriving at an intriguing conclusion, one that may foreshadow the suppression of the Jesuits in France: “They are considered as individuals of choice among many others because of their superior talents and their qualities. They are seen as very skillful people, always succeeding in their understanding and outperforming all others in sensitivity and perceptivities. . . . I notice that they have enemies in Canada.”[11]

Bonnécamps’s Research and Writing

One noteworthy aspect of Bonnécamps’s style of scientific research was his emphasis on precise measurements and the proper tools to obtain such measurements. Throughout most of his writings, including the journal of 1749, he bemoans the lack of precise tools and his hassles in attempting to procure them. One of his first tasks upon arrival at the Quebec College, and obviously after an inspection of the equipment present there, was to write to the intendant—an intermediary between the people and higher government officials—of Quebec, Gilles Hocquart, requesting a second pendulum, a magnet, and a telescope to be eventually mounted on the college roof as an observatory.[12]

After estimating the cost of these items to be between one thousand to twelve hundred francs, Hocquart made certain to receive permission from his superior before procurement. In this request dated October 29, 1744, Hocquart speaks highly of Bonnécamps and offers us a glimpse of his plan for science education in Quebec:

Mister Bonecan [sic], professor of hydrography, has let me know that he had been unable so far, to make any astronomical observation, from lack of necessary instruments: he would need a pendulum making seconds and a lens mounted on a quarter of a circle. He asked me to request from you, monsignor, these instruments.

One can construct at the College of Quebec a site on the roof to make observations. Since Father de Bonecan has been in Canada, he has very much improved [his students’] knowledge of mathematics, and he intends to make himself more and more useful to the promotion of the higher sciences.[13]

Having not received the requested equipment some years later, Bonnécamps once again requested these instruments from the new intendant, François Bigot, who wrote another letter to the Ministry of the Marine on October 9, 1748, stating that

Father Bonnecan [sic], Jesuit, professor of mathematics, has let me know that he needed the equipment for the teaching of young people that devote themselves to navigation: a pendulum marking seconds, a telescope, a quarter circle of three feet radius mounted with a lens instead of pinules, and a magnet stone, since the one he has is weak.[14]

Bonnécamps clearly wanted to promote the cutting-edge instruction of science through proper equipment. (It should be noted that he never received these items before his famous journey nine months later.)[15]

The first extant publication of Bonnécamps’s research in Quebec dates to 1747. The Jesuits of France published a journal, Mémoires de Trévoux,[16] named for the small town and capital of the principality of Dombes, where it was printed. The administration of the publication was centered in Paris at the College of Louis-le-Grand. Bonnécamps used this publication to transmit his scientific research to Europe. Unfortunately, only one of his publications in this journal has survived, an account of an intriguing meteorological observation recorded on June 12, 1746 in Quebec. This account, published in the journal in March 1747, is described by Bonnécamps as a “luminous arc” that appeared in the sky. The northern tip of this arc seemed as “a source of light where strong rays jutted out to spread a sort of daylight on the objects.”[17] Bonnécamps describes the light as somewhat different than northern lights, an astronomical and meteorological event that was extremely unlikely during the summer: “We could not see bursts of fire from these sparkling columns or flaming garlands that one can see in the ordinary northern lights.”[18] The phenomenon lasted for about an hour without any change and in the end completely vanished.[19]

In 1750, Bonnécamps would submit his most famous scientific writings, “An Account of the Voyage of the Beautiful River [Belle-Rivière] Made in 1749, under the Direction of Monsieur de Céloron.”[20] The account is written to General La Galissonière, governor-general of Canada, who commissioned the journey. Hearing reports that the English had begun to cross the Allegheny River and then infiltrate the Ohio Valley, the governor wanted Céloron’s group to take back possession of these lands in the name of France.

A total of six metal plates would be positioned along the root of the journey in the Belle-Rivière. The first lead plate was buried on July 29, 1749 near present-day Warren, Pennsylvania, at the supposed beginning of the Belle-Rivière. Each plate differing in some minor particulars from the others, much pomp and circumstance were associated with the commissioning of each plate. For purposes of motivation and importance, I list what this first plate verbosely stated:

In the year 1749, of the reign of Louis XV, King of France, we Céloron, commander of the detachment sent by the Mr. the Marquis de la Galissonière, general commander of New France to re-establish tranquility in some villages of these counties, have buried that plaque at the confluence of the Ohio and Kananouangon [a Native village], on July 29, as a monument to the renewed possession that we took of the said Ohio River and of all of those who flow into it, and of all the land on both sides up to source of said rivers, the way that the preceding kings of France enjoyed or must have enjoyed, and which they maintained by arms and treaties, and especially by those of Ryswich [sic: Ryswick], Utrecht, and Aix-la-Chapelle. Have also displayed at the same place on a tree the King’s coat of arms. In witness thereof, having prepared and signed the existing statement, done at the entrance of the Belle-Rivière on July 29, 1749. All the officers have signed.[21]

The last of the six plates was buried along the Miami River in present-day Cincinnati, Ohio, on August 31, 1749.

Bonnécamps’s adventure left from Lachine, Quebec, near Montreal, on June 15, 1749 and would involve many perils. One protective characteristic of this expedition was the sheer number of men involved. Under the lead of Pierre-Joseph Céloron de Blainville and his second commandant, Pierre-Claude de Contrecouer, the detachment included nearly 250 men, including eight subordinate officers, six cadets, 180 Canadians, and around thirty Native Americans.[22]

Although political concerns were central to La Galissonière, he also had a strong interest in science, especially botany and zoology. Bonnécamps’s understanding of La Galissonière’s passions for these subjects is seen throughout his journal. Although never identified as a biologist or botanist or one who has much interest in these fields, Bonnécamps gives detailed observations of the flora and fauna he encounters throughout his journey.

In some sense, Bonnécamps may have been intermittently humoring La Galissonière, because between these interesting accounts of plants and animals were some very serious observations with regard to English encroachment. If not equally numerous to observations of flora and fauna, he gives several accounts of encounters with the English in almost every region. Peaceful for the most part, these encounters had the English submissively, and most likely, superficially, vacating the area where they were discovered. But this insidious situation would eventually prove detrimental to the French colonization of North America.

What is most surprising about this journal is the complete lack of any mention of anything religious. Although labeled as “chaplain” by Céloron and as a “missionary” by many commentaries on this journal, Bonnécamps almost never makes any mention of religious feast days or observances. On July 31, Saint Ignatius of Loyola Day, an important day for all Jesuits, the holy day of their founder, his journal is silent. On August 6, the Roman Catholic Feast of the Transfiguration, nothing is recorded. The supposition is that Bonnécamps was celebrating Mass nearly every day of the journey, and that this journal was for secular purposes.

From Bonnécamps’s writings, this expedition was clearly not a religious pilgrimage, nor was it a “missionary journey,” especially when one reflects on his recorded attitude toward Native Americans. Here, I discovered one of Bonnécamps’s “shadows.” On June 30, he comments that Native Americans are people “who are naturally lazy.”[23] On July 13, he reports that the journey was somewhat delayed since everyone had “to await our savages, who were amusing themselves with drinking rum at the portage.”[24](It should be noted that it was the French who introduced rum to the Native Americans.) Toward the end of the expedition on October 8, Bonnécamps has become very frustrated with his Native American traveling companions. The expedition once again spent a day waiting for them, a “class of men” Bonnécamps describes as having been “created in order to exercise the patience of those who have the misfortune to travel with them.”[25]

Yet the Native Americans were an essential part of the expedition. At about ten percent of the total expedition of 250 men, this group of Iroquois and Abenakis, although small, had a very important role, as they were needed to communicate and negotiate with the Native Americans they encountered along the journey. Throughout his journal, Bonnécamps records how Natives in the group would scout ahead for Native American villages and would often soothe tensions and conflicts should they arise. Bonnécamps records in mid-August that the lives of two officers on the expedition were spared by the intervention of an Iroquois that was not even a part of their group, “perhaps [the Natives who captured the officers] would have executed this threat if an Iroquois, who was by chance present, had not appeased the furious savages by assuring them that we had no evil designs.”[26]

Throughout this journal, it is difficult to understand how or whether Bonnécamps got along well with the other members of the expedition. Other than a handful of complaints about Native Americans, Bonnécamps says little negative or positive about anyone else on the expedition, though it does appear he got along well with the officers. On October 6, he reports that “Monsieur de Céloron had the goodness to permit me to go the fort [Detroit] with some officers.”[27] The last two paragraphs of the 1750 journal are loaded with praise for the officers and subalterns, and especially for Céloron, “a man attentive, clear-sighted, and active; firm, but pliant when necessary; fertile in resources, and full of resolution—a man, in fine, made to command.”[28] Whether as their past teacher or friend, Bonnécamps had close friendships with military people, particularly naval officers, who would support and protect him later in life.

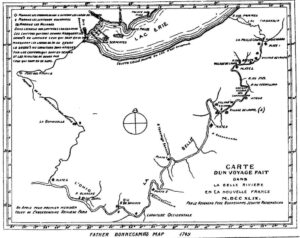

Bonnécamps’s central role in this expedition is noted nearly daily when he meticulously records the latitude and longitude of nearly every major stop and noteworthy place, such as forts and towns, to the nearest “minute” (one-sixtieth of a degree). The record of these numbers would be the map enclosed with the journal (see fig. 1).

Figure 1. Bonnécamps’s Map (1749).[29]

La Galissonière must have found Bonnécamps’s conclusion to the 1750 journal ominous because nearly every page chronicles the English infiltrating the area in greater and greater numbers while also deepening stronger bonds of commerce and trade with Indigenous peoples of various tribes. Four years after the journal was presented to La Galissonière, the French and Indian War would erupt.

The decade after the 1749 expedition (1749–59), with regard to Bonnécamps’s daily life, was fairly tranquil, but two major historical events continued to ferment before eventually erupting: the French and Indian War and the suppression of the Jesuits in France. What remains from this period are four letters. Three of these letters Bonnécamps wrote to a fellow scientist and friend in France, Joseph-Nicolas Delisle (1688–1768). In these letters, we come to understand what activities and thoughts kept Bonnécamps occupied during the decade after the famous journey down the Ohio River. The fourth letter, one of the most insightful into Bonnécamps’s personality, written to Pierre-Philippe Potier, the Jesuit superior of the Native American mission, further supports Bonnécamps’s activities during this period.

Delisle had something of a reputation in the world of eighteenth-century science. He was called to Saint Petersburg by Peter the Great (r.1682–1725) to found and administer a school of astronomy there. Arriving in 1726, after the tsar’s death, Delisle eventually became quite famous. He returned to Paris in 1747, building his own observatory in the palace of Cluny. Delisle’s brother, Guillame, was also a hydrographer, having published two major maps of North America: one of the Mississippi and one of the French regions of the Caribbean.

That Delisle and Bonnécamps became such close friends is not surprising given their common interests and backgrounds. As well as being an astronomer, Delisle was also a geographer in the French Navy. They were clearly close friends because Bonnécamps concludes each of these letters pretty much as he did the one dated October 30, 1757: “Allow me before ending this letter to ask for the continuity of our friendship. I assure you that no one is more attached and respectful of you than your humble, de Bonnécamps [signature].”[30] How each came into the acquaintance of the other is unclear. Most likely the reputations of both, particularly Bonnécamps’s fame after the 1749 journey, brought them together.

The first of three letters, sent from Quebec and dated October 30, 1754,[31] discusses three topics that are found in the other letters as well. The first common point of discussion is maps. Bonnécamps thanks Delisle for a copy of a map of Delisle’s “discoveries” of North America. Bonnécamps comments that the geography of North America is very poorly known and is only now beginning to be understood. It is not clear exactly what Delisle’s “discoveries” were, although they most certainly resulted from observations from maps rather than actual travels. The second point of discussion is the memoirs of Admiral de Fonte de Fuentes, a topic revisited in great detail in the next letter. Finally, Bonnécamps concludes this letter by promising to share his measurements with Delisle “as soon as they are publishable.”[32]

Strongly reminiscent of the October date of submission of his journal entry to La Galissonière, this letter written to Delisle, and the two others, are each dated in late October. This time of year was when summer research results had been tabulated. It would also have been when many ships were departing Quebec for France, as he mentions in his 1749 journal submission.

Other than to lament that the travels to obtain results were “long,” Bonnécamps’s letter to Delisle makes no explicit mention of when and where these measurements of this first letter were made. He does state in this letter that “I am coming from a long travel that has given me the opportunity to make several geographical measurements.”[33]

This journey is corroborated in a decree of François Bigot, intendant of Quebec, dated June 18, 1754.[34] The decree reports that another Jesuit, Pierre-René Floquet, has been asked to assume the position of hydrographer of the king in Bonnécamps’s absence that summer. Another such decree from the previous year, dated July 20, 1753, reported that Bonnécamps was to be sent to the “higher countries,” regions in the far north of New Canada, for measurements.[35] During this trip, he was replaced by another Jesuit, Pierre-Regis Billiard, as geographer of the king in Quebec. Billiard was a Jesuit scholastic teaching at the college in Quebec in 1749. He must have been studying hydrography in the subsequent years.

There is evidence that Bonnécamps made four successive trips, one for each summer of the years 1752–55. On June 25, 1752, he was at Fort Frontenac, present-day Kingston, Ontario, making some astronomical observations. This we know from a letter written to Potier, the superior of the Native American mission of Ile-aux-Bois-Blancs (sic: Île au Bois Blanc), a Huron mission near Quebec. Bonnécamps was not having a pleasant experience during this trip:

Reverend Father, I take liberty to write to you. You will perhaps be surprised of the date of my letter, since you believe me in Québec and I am not. But on the contrary I am a hundred leagues; no, thank God, not to stay, but passing to make astronomical observations with a quarter circle that the minister was kind enough to send on.[36]

It is comical to note that Bonnécamps finally received his quarter circle after having asked the intendant twice, the first time being eight years previous.

This letter of Bonnécamps is one of the most revealing about his personality. As mentioned earlier, the letter concludes with Bonnécamps’s request for tobacco, but within the letter are some cheeky comments about fellow priests. He refers to having visited a Jesuit he refers to as “prunes” who appeared to be in good health and a person who seems to like Quebec, “whatever he may say to the contrary.”[37] He also mentions that a priest, Pico di Miradola, from the Fort of the Presentation, had baptized 180 catechumens who received their catechetical knowledge from Pico, “who never knew how to jabber Iroquois.”[38] Bonnécamps goes on to report that this massive baptism ceremony cost 1,500 “pounds Tournois,” a sum certain to be “incredible” to Potier. Before his request for tobacco, Bonnécamps pens a cryptic conclusion about an unknown traveling companion: “My time is about up: my dear Granny says that it is time for me to go to bed and leave the lodging clear for the rest of the household.”[39]

In the second letter to Delisle, dated October 23, 1755,[40] Bonnécamps presents Delisle with various maps of the Great Lakes: Ontario, Huron, and Erie, as well as a corrected map of the Ohio River. He then goes on to describe his summer travels that year on Lake Erie and regions near the Bay of Sandusky (Ohio). In this letter, Bonnécamps complains about the grueling conditions of canoe travel, absent from the 1750 journal:

But when you are aware of the way one travels in this country, you will not have any difficulty to admit that obtaining [hydrographic measurements] is almost impossible. As a means of transportation, we have a canoe that can barely contain the things for survival. We leave at two or three in the morning, and we camp only long after the sunset. If we stop, it’s only because of bad weather. It is because of bad weather that we cannot make observations or even work.[41]

Bonnécamps then vents some frustration about how the agenda of the canoeing party adversely affects good measurements:

I was obliged on Lake Erie to leave my convoy to be able to reach the Bay of Sandusky [to make measurements] . . . In order to have precise results, it would be necessary that the geographer would be master of his own way and as I have been, obliged to follow the detachment of troops that march in the whimsical pattern of the officer who commands them.[42]

Bonnécamps’s respect for military officers seems to have waned a bit during the summer of 1755. As he concludes this tirade, he surprisingly reports that these conditions of travel did not completely destroy the accuracy of his measurements, most being nothing beyond two degrees.

Bonnécamps continues his ongoing indictment of poor equipment as the demon of good science when he comments in this second letter on the errors in the latitude of Quebec made by another Canadian cartographer, Jean Deshayes: “If you had the instrument that he used, your surprise would end soon. It is a piece of wood nearly eight inches of diameter covered with silver divided into 360 degrees. Such as instrument, an observer, no matter how skillful, will make a mistake of seven to eight minutes.”[43]

Bonnécamps then offers some “Jesuit insight” into some statements Delisle makes about a topic he is researching. Delisle was investigating the suspicious travels of Admiral Fonte de Fuentes, a Spanish or Portuguese sailor. Bonnécamps comments on page 22 of Delisle’s paper, where it was reported that “the Admiral Fonte de Fuentes and Captain Leonardo with two other Jesuits of whom one accompanied Captain Leonardo in his discovery. Both of whom went to advance to sixty-six degrees north in their mission and made very surprising observations.”[44]

Bonnécamps finds that statement incredulous since “no Jesuits of Canada have ever gone so far in North America,”[45] but he does offer the outside chance that these Jesuits could have been from Spain. His advice to Delisle is to simply write to the Jesuits of Spain and ask if they have any knowledge of the settlement in the far north Indian town of Conasset. Bonnécamps is not ready to completely dismiss the assertion, since there were Jesuits as far north as the fifty-fifth parallel in 1640. But his overall tone indicates strong doubts. Others would later prove that these travels and the associated stories were all fictitious.[46]

In retrospect, Bonnécamps’s life had not radically changed in the early years after his 1749 expedition. He was still teaching full time at the college while making summer expeditions to various bodies of water. A comparison of the province of France Jesuit catalog for New France in 1756 still lists “Pierre Jean de Bonnécamps” as a professor of hydrography, but he is now also listed as “confessor in the church, advisor.”[47] Just what an “advisor” did in a Jesuit community is unclear. Bonnécamps may have been a spiritual director or possibly a consulter to the rector of the community. From this listing, it is apparent that he now had more time for pastoral concerns. It is worth noting, as well, that Bonnécamps is one of only a handful of Jesuits, two priests and three brothers, who lived in the Quebec Jesuit residence in 1756 that were stationed there in 1749. The French Jesuits were possibly beginning to shift their manpower as the political tensions in the region increased.

Bonnécamps left Quebec for France in the autumn of 1757. This we know on two accounts. First, he is no longer listed in the Jesuit catalog of New France for 1757.[48] And second, a letter dated September 10, 1757 mentions that a non-Jesuit, Gabriel Pellegrin, had received a hydrographic commission in Bonnécamps’s absence.[49] This trip to France would be Bonnécamps’s first return to France in the thirteen years he had been assigned to the Quebec Jesuit residence as professor of hydrography.

Bonnécamps would later return in the spring of 1758, leaving Paris on March 25, 1758 and boarding a boat bound for Canada from La Rochelle. As mentioned previously, Bonnécamps always enjoyed warm relations with French naval officers, most likely due to his contacts and influence at the Quebec college while teaching hydrography. One prominent military officer, Louis-Antoine Comte de Bougainville, wrote a letter of recommendation on behalf of Bonnécamps to his friend and protector, Madame Hérault, before this trip to France.

Dated Quebec, November 8, 1757,[50] this letter indicates two pressing aspects of Bonnécamps’s life at this time—his increasing need for benefactors in France, and its related corollary: the growing suspicions about the Jesuits there. Within five years, these suspicions would result in the complete suppression of the Jesuits in France. As Bougainville writes in his letter of recommendation, “[Bonnécamps] is a Jesuit, but as a Jesuit, the only thing he has [in common with them] is his cassock.”[51]Clearly reflecting increasing hostility toward Jesuits and wanting to separate Bonnécamps from other “disreputable” Jesuits, he does point out one innocuously negative aspect of Bonnécamps: “The only thing you will find is that he speaks fast.”[52]

Bonnécamps’s several months in France had him visiting many people, including Madame Hérault. He took some time to visit his friend and correspondent, Delisle, as we learn in a third letter dated Quebec, October 30, 1758.[53]

At the beginning of this letter, Bonnécamps thanks Delisle “for the affection and friendship you showed me during my stay in Paris”[54] and apologizes for his lack of astronomical observations. But he then goes on to explain the reason: his busyness upon his arrival in Canada, where he was sent for “missionary duties” immediately after disembarking in Montreal.[55] Just what these “missionary duties” were is unknown. As we will discover, a later letter of Bonnécamps may provide a hint.

After happily reporting his safe crossing from France to Canada in a very short thirty-four days, Bonnécamps continues the letter with depressing details about the increasing losses the French were suffering against the English in New France. What I find fascinating about this part of the letter is Bonnécamps’s keen insight into military strategy. Certainly, his years of teaching and socializing with military officers had influenced him. We are once again reminded of Bonnécamps’s knowledge of fort construction. In his discussion of the surrender of Louisbourg (July 27, 1758), a strategic fort guarding the entrance to the Saint Lawrence Seaway and located in present-day Nova Scotia, he writes:

One mistake we made, according to me, in defending this place, was to not have used all of our forces to prevent them from coming down. The only means to keep this place, that has no other defense, was a trench. This could have prevented the enemy’s capture of the city. Add to the fact that the walls of that fortress were made with a mortar of salty sand. And it is obvious by experience that sea sand does not mix with that base mortar. It makes a very bad mortar. And those walls needed repairing every spring.[56]

Manpower was the deciding factor in many of these battles. As Bonnécamps presciently predicts: “In one word, to tell you things as they are happening now, we should not be surprised if Canada falls into the hands of the English. They have more than sixty thousand men, and we have only twelve thousand to oppose them.”[57]

Bonnécamps’s only hope for the French defeat of the English was that Holland and Spain would join France in the defense of Canada. But as he analyzes the proposal further, he concludes that Spain’s influence is also dying in North America: “The English openly say that as soon as the war with France ends, they will declare war with Spain.”[58]

Bonnécamps concludes this third and final letter to Delisle with one request—some maps for a third unnamed party:

Should I dare to take the freedom to beg of you to buy for me seven maps [sic: I count eight]: the four main parts of the world, one world map, one map of France, as it was drawn in the memoirs of the French Academy, the map of Canada, the map of Paris, and to send many copies. The person who is asking to buy these maps wants those that are beautiful and good. So I ask you not to spare anything to do that—do your best.[59]

In true Jesuit fashion, the funds for these maps will be supplied by a Jesuit brother, acting as minister or treasurer, “Brother Duval who remains in Louis the Great College will give you the money necessary for these maps.”[60]

Within a year of this last letter to Delisle, in the fall of 1759, the French would surrender Quebec to the English. Bonnécamps’s fifteen-year tenure as “professor of hydrography” at the Jesuit College of Quebec was rapidly coming to an end.

The French and Indian War

Much has been written about the French and Indian War, a war some consider the first “world war.”[61] From 1754 to 1763, in various places around the globe, England was battling France for colonized regions they “shared.” In North America, England’s goal was to force France out of the entire region of present-day Canada and the United States. There was never real peace along the disputed boundaries between these two countries in North America. But the growing immigration of English residents into these regions increased tensions with both the Native Americans and the “guest dwellers” among the Natives, the French.

The conquest of Quebec, Bonnécamps’s home in North America, was particularly brutal. On June 26, 1759, the English opened siege on Quebec, which officially surrendered two days later with over five hundred buildings in the city having been destroyed and even more having been damaged.

It is unclear whether Bonnécamps witnessed the destruction of Quebec firsthand or had already been in France at this time. His name is not listed in the 1759 catalog of Jesuit manpower for Quebec, although this does not necessary imply he was absent from Quebec that year.[62] The catalog is usually published after Jesuit assignments have been promulgated for that year, which is usually on August 15, the Feast of the Assumption. In any case, when the siege of Quebec began, the college would have been closed and the students forced to enlist in the military. If Bonnécamps had been teaching classes the spring semester of 1759, he would have been unable to sail back to France during that summer of violence.

It is unclear what the immediate fate would have been for the Jesuits remaining in Canada after the “conquest.” In an entry from November 13, 1759, an English historical journal of the period, Knox’s Historical Journal, states that “the Jesuits have received orders to depart town as soon as possible.”[63] That all the Jesuits did not leave Canada can been seen in the life of the Jesuit Pierre-René Floquet, the “substitute” hydrographer for Bonnécamps during the summer of 1753, who eventually died in Quebec on October 18, 1782.[64]

Heavily damaged, what remained of the Jesuit college in the fall of 1759 was used to lodge English troops. Built in 1666, the Jesuit church attached to the College of Quebec, the church where Bonnécamps took his final vows, was damaged and would eventually be destroyed in 1807.

In none of the existing documents does Bonnécamps mention his location during the siege of Quebec. He would definitely have returned to France by the fall of 1759, most likely returning to Caen, where he is found in 1761 once again teaching mathematics at the college.[65] Bonnécamps was probably teaching there when the decrees of the suppression of the Society of Jesus in France were promulgated in 1762.

Suppression of the Society of Jesus in France

Just like the French and Indian War, much has also been written about the suppression of the Society of Jesus in the eighteenth century. My goal here is to highlight the history of an event that would eventually strip Bonnécamps of a major component of his life: membership in the Society of Jesus. By the decrees of the suppression, Bonnécamps would also no longer have the right to teach in France and would have had to abandon his teaching post, as well as his career in teaching.

The years from 1762 to 1765 are something of a mystery with regard to Bonnécamps’s whereabouts. But surprisingly, we find him back in Canada around 1765 serving as a missionary priest along with another ex-Jesuit on the remaining French fishing islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon off the coast of present-day Newfoundland. The other Jesuit was François-Paul Ardilliers. We know Bonnécamps was in Canada around 1765–66 because of a letter he wrote to a French cleric, Pierre de LaRue, the abbé de L’Isle Dieu, justifying his ecclesiastical assignment and clerical faculties in these French fishing villages.

The complex situation that Bonnécamps found himself in with LaRue had political roots. By the Treaty of Paris (February 10, 1763), promulgating the end of the French and Indian War, France ceded Louisiana to Spain and Canada and all its possessions in the Gulf of St. Lawrence to Great Britain. But there was one exception in this agreement. France retained the islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, whose commercial and strategic importance were out of proportion to their size. On the surface, France argued that these islands were important for fishermen to carry on their cod fishing, a labor from which vast regions of Canada benefited. But it was also known that fishermen were a source of skilled sailors who could quickly be put into naval service.

LaRue believed that these islands were never part of the diocese of Quebec. Therefore, the bishops of Quebec never had the chance to claim jurisdiction there. When Quebec was ceded to England, the bishops of Quebec became English subjects and then had no jurisdiction over these islands anyway. Not being able to communicate with these two islands, LaRue make the decision to put Saint-Pierre and Miquelon under the direct responsibility of the Vatican.

In a letter dated Island of Saint-Pierre, June 15, 1766, Bonnécamps attempts to justify the canonical jurisdiction of their ministry to this leading cleric.[66] It appears that Bonnécamps may have been the pastor of Saint-Pierre, while Ardilliers was at Miquelon. Although he commends LaRue for his “zeal which you inflamed for the glory of God and salvation of souls,” two strong Jesuit mottoes, Bonnécamps makes his assertion quite clear: “It appears that you have been poorly informed about what is going on with our island, in regard to religion and the administration of sacraments.”[67]

What I find most intriguing about this final letter is Bonnécamps’s writing style. No longer speaking of scientific observations and measurements, he is making a very persuasive, if not somewhat aggressive argument, about the validity of his and his companion’s legitimate reason for being on these islands.

On July 21, 1766, LaRue wrote a letter from Paris about this situation to the cardinal prefect of the Propaganda Fide.[68] This very detailed letter carefully refutes each of Bonnécamps’s arguments while also justifying his own understanding of the issue. LaRue begins the letter by referring to the clerical situation at Saint-Pierre and Miquelon as an “abuse.” Bonnécamps would be sent home to France some years after this letter.

Bonnécamps most likely left North America in 1768 and then became a chaplain at the convict prison in Brest, France, in 1770.[69] This location was probably an assignment presented to him by the “bishop of his birthplace,” in accordance with the mandates of the Jesuit suppression in France.

Although there is only circumstantial evidence in this regard, Bonnécamps may have been encouraged to work in Saint-Pierre and Miquelon by a naval acquaintance. We know that Admiral François-Jean-Baptiste L’Ollivier de Tronjoly, a native of Bonnécamps’s hometown of Vannes, had a special commission to protect the French fisheries, including these two islands.

After being expelled from the islands, Bonnécamps would eventually take up residence in the admiral’s chateau in Brittany, now as a tutor to the admiral’s children.[70] Back to his life of teaching, he also renewed his passion for scientific inquiry. At the time he lived there, the chateau had a tower where he pursued meteorological observations. It was also recorded that in his later years he would sit for hours by the s spacious windows enjoying the bucolic surroundings of the chateau with its trees and many small lakes.

On May 28, 1790, Joseph-Pierre de Bonnécamps died at the chateau of Tronjoly.

Notes:

[1] Auguste Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps (1707–1790),” Canadian Royal Society Proceedings, 2nd ser., 3, sec. 1 (1897): 93–117, here 116.

[2] Nicholas P. Cushner, Why Have You Come Here? The Jesuits and the First Evangelization of Native America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006).

[3] The remaining Jesuit college building in Quebec City, now called St. Charles Garnier College, has an embossed date above the main doorway: 1635–1935.

[4] Patricia M. Ranum, Beginning to Be a Jesuit: Instructions for the Paris Novitiate circa 1687 (St. Louis, MO: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 2011).

[5] Auguste Gosselin, “Les jesuites au Canada: Le P. Bonnécamps, dernier professeur d’hydrographie au college de Québec, avant la conquête (1741–1759),” Canadian Royal Society Proceedings, 2nd ser., 1, sec. 1 (1898): 25–61, here 34.

[6] “Bonnécamps, Joseph-Pierre de,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, accessed October 2, 2024, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bonnecamps_joseph_pierre_de_4E.html.

[7] Gosselin, “Les jesuites au Canada,” 36.

[8] Gosselin, “Les jésuites au Canada,” 37.

[9] Bonnécamps would have been away on his boating expedition, floating somewhere on the Scioto River in present-day Ohio, at the time of Kalm’s visit.

[10] Gosselin, “Les jésuites au Canada,” 38.

[11] Gosselin, “Les jésuites au Canada,” 38–39.

[12] Gosselin, “Les jésuites au Canada,” 27–28.

[13] Gosselin, “Les jésuites au Canada,” 27–28.

[14] Gosselin, “Les jésuites au Canada,” 28.

[15] As we shall discover in a later letter, he eventually received the requested items some years later.

[16] These Mémoires began to be published in 1701.

[17] Gosselin, “Les jésuites au Canada,” 40.

[18] Gosselin, “Les jésuites au Canada,” 41.

[19] This phenomenon sounds as if it were a meteor or comet breaking up and burning through the atmosphere.

[20] Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., “Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France (1610–1791),” Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents 69 (1900): 151–99.

[21] Andrew Gallop, The Céloron Expedition in the Ohio Country 1749: The Reports of Pierre-Joseph Céloron and Father Bonnecamps(Westminster, MD: Heritage, 2008).

[22] Gosselin, “Les jésuites au Canada,” 41.

[23] Thwaites, “Travels and Explorations,” 157.

[24] Thwaites, “Travels and Explorations,” 159.

[25] Thwaites, “Travels and Explorations,” 191.

[26] Thwaites, “Travels and Explorations,” 179.

[27] Thwaites, “Travels and Explorations,” 191.

[28] Thwaites, “Travels and Explorations,” 199.

[29] “On This Day in Pittsburgh History: August 7, 1749,” Pittsburgh History Journal, August 7, 2010, accessed October 2, 2024, https://thepittsburghhistoryjournal.com/post/917628968/map-by-father-bonnecamps-1749-via-on-this-day.

[30] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 103.

[31] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 96–97.

[32] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 97.

[33] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 96.

[34] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 96n3.

[35] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 96n3.

[36] I discovered a translated version of this letter at the Jesuit Archives, Montreal, Quebec, Canada in the folder “Bonnécamps. P. Joseph-Pierre,” no. 593.

[37] Jesuit Archives, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, “Bonnécamps. P. Joseph-Pierre,” no. 597.

[38] Jesuit Archives, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, “Bonnécamps. P. Joseph-Pierre,” no. 597.

[39] Jesuit Archives, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, “Bonnécamps. P. Joseph-Pierre,” no. 597.

[40] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 97–99.

[41] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 97.

[42] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 97–98.

[43] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 98.

[44] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 98.

[45] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 98.

[46] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 98.

[47] Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., “Catalogue of the Persons and Their Offices of the Province of France of the Society of Jesus at the End of the Year 1756: Missions of North America in New France,” Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents 70 (1901): 83.

[48] Gosselin, “Les jésuites au Canada,” 57.

[49] Gosselin, “Les jésuites au Canada,” 58n2.

[50] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 100.

[51] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 100.

[52] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 100.

[53] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 100–103.

[54] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 100–101.

[55] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 101.

[56] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 101–2.

[57] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 102.

[58] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 102.

[59] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 102.

[60] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 102.

[61] William M. Fowler Jr., Empires at War: The French and Indian War and the Struggle for North America, 1754–1763 (New York: Walker & Company, 2005).

[62] Gosselin, “Les jésuites au Canada,” 108.

[63] Gosselin, “Les jésuites au Canada,” 59n3.

[64] Gosselin, “Les jésuites au Canada,” 57n5.

[65] Gosselin, “Les jésuites au Canada,” 59.

[66] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 108–10.

[67] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 108.

[68] Gosselin, “Encore le P. Bonnécamps,” 110–13.

[69] “Bonnécamps, Joseph-Pierre de,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

[70] Auguste Gosselin, “Le château de Tronjoly, derrnière du P. de Bonnécamps,” Canadian Royal Society Proceedings, 2nd ser., 4, sec. 1 (1898): 33–34.

“Bonnécamps, Joseph-Pierre de.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bonnecamps_joseph_pierre_de_4E.html (accessed October 2, 2024).

Cushner, Nicholas P. Why Have You Come Here? The Jesuits and the First Evangelization of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Fowler, William M., Jr. Empires at War: The French and Indian War and the Struggle for North America, 1754–1763.New York: Walker & Company, 2005.

Gallop, Andrew. The Céloron Expedition in the Ohio Country 1749: The Reports of Pierre-Joseph Céloron and Father Bonnecamps. Westminster, MD: Heritage, 2008.

Gosselin, Auguste. “Encore le P. Bonnécamps (1707–1790).” Canadian Royal Society Proceedings, 2nd series, 3, sec. 1 (1897): 93–117.

Gosselin, Auguste. “Le château de Tronjoly, dernière du P. de Bonnécamps.” Canadian Royal Society Proceedings, 2nd series, 4, sec. 1 (1898): 33–34.

Gosselin, Auguste. “Les jésuites au Canada: Le P. Bonnécamps, dernier professeur d’hydrographie au collège de Québec, avant la conquête (1741–1759).” Canadian Royal Society Proceedings, 2nd series, 1, sec. 1 (1898): 25–61.

“On This Day in Pittsburgh History: August 7, 1749.” Pittsburgh History Journal, August 7, 2010. https://thepittsburghhistoryjournal.com/post/917628968/map-by-father-bonnecamps-1749-via-on-this-day (accessed October 2, 2024).

Ranum, Patricia M. Beginning to Be a Jesuit: Instructions for the Paris Novitiate circa 1687. St. Louis, MO: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 2011.

Thwaites, Reuben Gold, ed. “Catalogue of the Persons and Their Offices of the Province of France of the Society of Jesus at the End of the Year 1756: Missions of North America in New France.” Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents 70 (1901): 83.

Thwaites, Reuben Gold, ed. “Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France (1610–1791).” Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents 69 (1900): 151–99.

- Title: Joseph-Pierre de Bonnécamps: A Jesuit Scientist Living in Turbulent Times

- Author: John D. Cunningham, S.J.

- Article Type: Research Article

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.51238/38Z7fp6

Language: English - Pages: 273–293

- Keywords: Jesuit science; hydrography; cartography; Quebec; Joseph-Pierre de Bonnécamps

- In: Jesuit Educational Quarterly

- In: 2nd ser., Volume 1, Issue 2

- Received: 29 July 2024

- Accepted: 05 August 2024

- Publication Date: 28 April 2025

Last Updated: 28 April 2025 - Publisher: Institute of Jesuit Sources

- Print ISSN: 2688-3872

- E-ISSN: 2688-3880

APA

Cunningham, J. D., S.J. (2025). Joseph-Pierre de Bonnécamps: A Jesuit scientist living in turbulent times. Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 1(2), 273–293. https://doi.org/10.51238/38Z7fp6

CMOS

Cunningham, John D., S.J. 2025. “Joseph-Pierre de Bonnécamps: A Jesuit Scientist Living in Turbulent Times.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., 1, no. 2: 273–293. https://doi.org/10.51238/38Z7fp6.

MLA

Cunningham, John D., S.J. “Joseph-Pierre de Bonnécamps: A Jesuit Scientist Living in Turbulent Times.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., vol. 1, no. 2, 2025, pp. 273–293. https://doi.org/10.51238/38Z7fp6.

Turabian

Cunningham, John D., S.J. 2025. “Joseph-Pierre de Bonnécamps: A Jesuit Scientist Living in Turbulent Times.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., 1, no. 2: 273–293. https://doi.org/10.51238/38Z7fp6.

© Institute of Jesuit Sources, Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, All Rights Reserved