Research Article

Special Section: Circa Missiones. Jesuit Understandings of Mission through the Centuries

‘Mission’ in (Con)text: A Philological Examination of Its Shifting Role in Jesuit Educational Discourse

Guterres, A. Taiga. “‘Mission’ in (Con)text: A Philological Examination of Its Shifting Role in Jesuit Educational Discourse.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., 1, no. 2 (2025): 255–72. https://doi.org/10.51238/Tv5vs7H.

The first series of the Jesuit Educational Quarterly (JEQ), published from 1938 to 1970, served as the official bulletin of the Jesuit Educational Association in the United States, offering a crucial lens into the evolving discourse of mission within Jesuit education. This study examines the shifting meanings and applications of mission—from apostolic identity to institutional purpose—through a philological and historical analysis of JEQ articles. By tracing occurrences of mission within the journal, the study reconstructs its semantic development across a transformative period in Jesuit education. Through a qualitative and quantitative review, it highlights the evolving relationship between mission and education, the integration of American Jesuit schools into broader missionary networks, and the eventual emergence of the institutional mission statement. By situating these developments within broader ecclesiastical and societal contexts, this article explores how mission became central to Jesuit educational identity and discourse.

Keywords:

mission, mission statement, Jesuit Educational Quarterly, Jesuit Educational Association

Preface

In the history of Jesuit educational discourse, the term mission has been pivotal, embodying a spectrum of interpretations and applications deeply rooted in the Society of Jesus’s foundational goals and principles. In the United States, it is not uncommon today for there to be an Office of Mission and Ministry at a Jesuit university, an Officer of Mission and Identity at a Jesuit school, or some dedicated position or department that employs the term mission. While the current term of a mission in educational settings is used in various, and sometimes polyphonic ways, it is often linked to the institution’s formal mission statement, signifying a sense of purpose or institutional identity.

The centrality of the relation of mission and mission statements in Jesuit education in the United States is demonstrated by an article written by Charles L. Currie, S.J. (1930–2019; president 1997–2011), former president of the Association of Jesuit Colleges and Universities (AJCU), who wrote:

Mission statements and promotional materials . . . celebrate what is distinctive about a particular tradition. Most importantly, however, the tradition is being shared with trustees, administrators, faculty, staff, and students through orientation and ongoing educational and experiential programs. The challenge is to show how the sponsoring identity creates a special educational experience by influencing both the curriculum and the entire campus culture.[1]

Currie’s analysis underscores how mission statements function as a rhetorical and organizational tool to articulate institutional identity within Jesuit education. His comparative study of the twenty-eight Jesuit colleges and universities of the AJCU at the time—alongside a sample of other Catholic institutions—sought to illuminate the distinctive Jesuit character embedded within these statements. This emphasis on mission as an orienting framework remains central in contemporary Jesuit higher education. One of the most recent guiding documents of the AJCU, Characteristics of Jesuit Higher Education: A Guide for Mission Reflection, outlines the ‘Mission Priority Examen’ (MPE), a self-study process for Jesuit colleges and universities to reflect on their Jesuit and Catholic identity.[2]

The historical development of mission in Jesuit education, however, is not merely a question of contemporary institutional practice. [3] It is a term deeply embedded in the history and intellectual formation of Jesuit pedagogy, its meaning shifting across time, contexts, and rhetorical uses.[4] To understand how mission has been articulated within Jesuit education, it may be helpful to turn to one a significant source documenting internal discourse among Jesuit educators in twentieth century-United States—the Jesuit Educational Quarterly (JEQ).

Situating the Jesuit Educational Quarterly in History

The first series of the JEQ served as the official bulletin of the Jesuit Educational Association (JEA) of the American Assistancy and was published from 1938 to 1970.[5] As such, it provides a particularly rich resource for analyzing the ways in which mission was articulated within Jesuit education. Spanning the generalities of Wlodimir Ledóchowski (g. 1915–42), Jean-Baptiste Janssens (g. 1946–64), and Pedro Arrupe (g. 1965–83), the periodical reflects the influence of changing leadership on Jesuit educational priorities. The period covered by the first series of JEQ is an era marked by internal institutional reforms, external pressures from accreditation bodies, and broader shifts in American higher education.

The 1934 Instructio pro Assistentia Americae de ordinandis universitatibus, collegiis ac scholis altis et de praeparandis eorundem magistris [Instruction for the American Assistancy on the Organization of Universities, Colleges, and High Schools and on the Preparation of their Teachers] was a foundational document for Jesuit education in the United States and played a crucial role in this transformation.[6] Emerging from a broader push for coherence in Jesuit educational efforts, the Instructio articulated a structured approach to Jesuit institutional identity, setting the stage for subsequent decades of discourse. The establishment of the JEA, as outlined in the Instructio, marked a formalized commitment to collective educational efforts, reflecting a shift from individual institutional autonomy toward a more unified network of Jesuit colleges and universities. From this document, the JEA was created and subsequently, the JEQ was established.[7]

As a platform reflecting internal discussions, institutional priorities, and pedagogical frameworks, the JEQ captures how Jesuit educators engaged with the concept of mission across decades. It functioned as an intellectual space where administrators, faculty, and provincial leaders debated challenges, documented policies, and reflected on the evolving identity of Jesuit educational institutions. Given its role as the primary organ of the JEA, the JEQ allows for a reconstruction of institutional self-understanding and the rhetorical frameworks that shaped Jesuit higher education in the twentieth century.

‘Mission’: A Philological Inquiry in (Con)Text

There are many ways through which the semantics of concepts can be examined in historical inquiry. The evolution of language, the shifting contexts in which terms are deployed, and the various institutional and cultural forces shaping their meaning offer multiple paths of exploration. In the case of mission, its historical trajectory within Jesuit education can be approached through a philological lens, tracing its occurrences within a significant textual corpus to better understand its rhetorical and conceptual shifts over time.

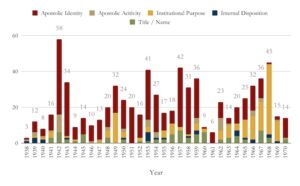

A systematic review of JEQ articles allows for the reconstruction of the evolving meanings of mission, grouping instances into broad semantic fields: (1) mission as an apostolic identity, (2) mission as an apostolic activity, (3) mission as an institutional purpose, (4) mission as an internal disposition, and (5) mission within titles and names. These categories emerged through an iterative process, where initial clusters of meaning were tested and refined against the broader textual corpus.

JEQ will be treated as a source, with occurrences analyzed based on pre-hypothetical clusters of meaning, tested, and then re-grouped to form more convincing semantic areas. This methodological approach, while not the only possible avenue for understanding mission in Jesuit education, offers some understanding in examining how meaning is formed, reinterpreted, and institutionalized over time. It reveals how mission evolved from a primarily apostolic role to one that also structured institutional identity, governance, and pedagogy. While early references in the JEQ primarily emphasized the missionary identity of Jesuits, later decades saw an increasing use of mission to articulate the purpose of Jesuit universities, particularly in the 1960s. This shift aligns with broader changes, including Vatican II, shifts in university governance, and the integration of lay faculty and administrators into Jesuit institutions.

By situating mission within this semantic-historical framework, the analysis brings to light the ways in which language itself shapes and reflects institutional transformations. In doing so, it provides insight into how Jesuit educators, particularly in the United States, historically conceptualized their work, how mission became a central term in institutional rhetoric, and how its evolution mirrors larger developments in the Society of Jesus and Catholic higher education.

Five Emergent Conceptual Categories of Mission

A systematic review of 1,299 articles from the JEQ between 1938 and 1970 reveals that the term mission was employed a total of 737 times in five primary ways, each reflecting distinct yet overlapping conceptualizations of the term:

1. mission as an apostolic identity;

2. mission as an apostolic activity;

3. mission as an institutional purpose;

4. mission as an internal disposition; and

5. mission within titles or names.

Each category reflects a different facet of Jesuit educational thought and its relationship to the broader apostolic goals of the Society. Quantitatively, the distribution of mission usage demonstrates clear trends over time. The apostolic identity category dominates, comprising 58.07% of all occurrences, while institutional purpose accounts for 21.85%, reflecting the increasing shift in discourse toward education as a formalized institutional mission. The remaining categories—apostolic activity (6.11%), internal disposition (3.53%), and title/name-related usage (10.45%)—highlight more specialized applications of the term. The analysis of these trends over time reveals distinct historical patterns that align with broader developments in Jesuit education.

Figure 1. Instances of ‘mission’ in JEQ 1938–70, over time.

| Table 1: Instances of ‘mission’ in JEQ 1938–70, summary table. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Apostolic Identity | Apostolic Activity | Institutional Purpose | Internal Disposition | Title / Name | Total |

| 1938 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 1939 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 12 |

| 1940 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 8 |

| 1941 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 16 |

| 1942 | 42 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 58 |

| 1943 | 30 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 34 |

| 1944 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 9 |

| 1945 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 14 |

| 1946 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| 1947 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| 1948 | 11 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 20 |

| 1949 | 15 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 32 |

| 1950 | 16 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 24 |

| 1951 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| 1952 | 13 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 16 |

| 1953 | 28 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 41 |

| 1954 | 21 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 27 |

| 1955 | 10 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 17 |

| 1956 | 7 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 18 |

| 1957 | 33 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 42 |

| 1958 | 26 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 31 |

| 1959 | 22 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 36 |

| 1960 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 9 |

| 1961 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 1962 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 23 |

| 1963 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 14 |

| 1964 | 9 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 20 |

| 1965 | 12 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 25 |

| 1966 | 14 | 3 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 32 |

| 1967 | 11 | 2 | 16 | 0 | 7 | 36 |

| 1968 | 1 | 0 | 39 | 2 | 3 | 45 |

| 1969 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 15 |

| 1970 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 14 |

| Total | 428 | 45 | 161 | 26 | 77 | 737 |

| % | 58.07% | 6.11% | 21.85% | 3.53% | 10.45% | 100% |

Mission as an Apostolic Identity

The most prevalent category, mission as an apostolic identity, accounted for 428 instances (58.07%) of all uses recorded in the JEQ. In the early decades of the journal (1938–1950), this was overwhelmingly the dominant meaning of the term, reinforcing the traditional Jesuit understanding of mission as a geographical and apostolic assignment or identity. The term frequently referred to Jesuit assignments in overseas missions, such as the Philippine Mission, China, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Jamaica, Belize, Baghdad, and India. Domestic missions, though less frequent, also appeared, including Alaska, Louisiana, and Buffalo.[8]

This category saw its highest frequency in 1942, with 42 recorded instances, coinciding with World War II and increased attention to Jesuit activity abroad, as well as the preparation of young men who would be drafted to the war. During this period, American Jesuit missionaries in the “Far East, Near East, and Caribbean countries,” were engaged in wartime educational and pastoral work, which was reflected in reports within the JEQ.[9] It is also notable that many Jesuit high schools were discussed as holding fundraisers, ‘mission drives,’ and ‘mission collections,’ during the last 1940s and early 1950s.[10] However, by the 1960s, occurrences of mission in this category began to decline sharply, as Jesuit educational institutions increasingly adopted a more institutionalized, rather than personal or apostolic, framework for mission.

A notable distinction emerges in the way missionary identity was portrayed relative to education. While many Jesuits engaged in both teaching and missionary work, the JEQ often juxtaposed the missionary and the educator as distinct roles. This distinction was further reinforced by specialized terms such as “bush missionary,”[11] referring to those in remote regions, and “mission bands,”[12]groups of Jesuits who traveled across U.S. schools to promote awareness of the foreign missions and encourage vocations.

By the late 1960s, mission as an apostolic identity became far less central in the JEQ, though not completely gone by any means, signaling a broader institutional transition in Jesuit education, where the missionary was no longer the primary figure of Jesuit engagement, and the concept of mission itself was beginning to be reoriented toward educational institutions.

Mission as an Apostolic Activity

The second category, mission as a form of apostolic activity, accounted for 45 instances (6.11%) in the dataset. While significantly less common than mission as an identity, this category highlights how mission was framed as an action-oriented concept, particularly in reference to evangelization and apostolic outreach.

While the evangelistic dimension of the mission is often implied within its apostolic identity and geographical context, a significant number of instances in the JEQ use mission as a categorical label to denote a specific type of work—referred to as mission work or missionary work—that was not necessarily tied to a particular place or geographical frontier. Rather than referring to a Jesuit’s personal identity as a missionary or a specific location, this category reflects the ways in which mission functioned as a distinct mode of activity within Jesuit education and pastoral outreach.

One of the most notable uses of mission in this sense was the concept of “student missions,” which appeared in discussions of annual retreats for students at Jesuit schools.[13] These student missions were framed as transformative experiences intended to cultivate religious formation and deepen students’ spiritual engagement, aligning with the broader Jesuit goal of shaping individuals in faith and moral discernment. The terminology of mission in this context suggests that even within the highly structured environment of Jesuit education, evangelization was not solely the work of priests in foreign lands but also an integral part of student formation.

Beyond the student context, the JEQ also references missionary work “at home and abroad”,[14] demonstrating that the category of mission was broad enough to encompass domestic apostolic efforts as well as foreign missions. This usage reinforces the idea that mission was not simply an inherited term from the Society’s early expansionist period but a continuously active and evolving category that could describe a range of religious activities. For example, missionary catechetical classes appear in the JEQ as a formalized initiative within Jesuit education, integrating religious instruction with the broader goals of evangelization.[15] Similarly, city-wide missions or urban missioners are discussed in relation to Jesuit outreach efforts in metropolitan areas, indicating that mission retained a strong evangelistic connotation even when applied in non-geographical contexts.[16]

This category also highlights an important semantic distinction within the JEQ: while all missionaries engaged in mission work, not all mission work was performed by missionaries in the traditional sense. The presence of mission in discussions of student retreats, catechetical instruction, and urban evangelization suggests that the concept was being used to define a type of apostolic labor that extended beyond the traditional mission territories of the Society. This underscores the flexibility of mission as a term within Jesuit discourse, demonstrating its ability to adapt to different educational and ministerial needs while retaining its core religious significance.

Mission as an Institutional Purpose

One of the most significant shifts in discourse is the increasing prevalence of mission as an institutional purpose, which comprises 161 instances (21.85%) of all occurrences. By the late 1960s, discussions of mission in the JEQ had undergone a noteworthy development, changing from an understanding of education as a subsidiary function of the Church’s apostolic mission to an articulation of Jesuit educational institutions as distinctive, though not independent, mission-driven entities. This transition, evident in a sharp rise in references to the educational mission of the university, was particularly evident in the writings of particular figures, most notably Patrick H. Ratterman, S.J. (1916–78) in 1967–68.[17] His contributions, which account for a significant portion of the recorded institutional references to mission during this period, reflect an intentional effort within the Society of Jesus to redefine the role of Jesuit higher education in an era of institutional and ecclesial change.

Earlier references in the JEQ (1940s–50s) primarily framed Jesuit education as an extension of the Church’s mission, emphasizing the role of schools in Catholic evangelization, doctrinal instruction, and moral formation. However, this perspective began to shift in the early 1960s, when mission was increasingly used to describe educational institutions as direct agents of apostolic work, rather than merely participating in a broader ecclesial effort. This shift was influenced by Vatican II’s renewed emphasis on Catholic higher education, which encouraged universities to engage with the modern world in ways that went beyond traditional theological instruction.

Ratterman’s writings in 1967 and 1968 represent the larger movement in Jesuit educational administration towards this conceptual transition. In his discussions, he explicitly argued for a reorientation of Jesuit universities around their educational mission, moving away from the older framework that had positioned them primarily as training grounds for religious and civic leadership. Instead, he pushed for an understanding of the university itself as an apostolic entity, one whose mission was not only to provide moral and intellectual formation but also to contribute directly to scholarship, cultural engagement, and social transformation. He emphasized the university’s ‘dual commitment’ to the ‘educational ideal of a true university,’ in addition to the ‘commitment to the Catholic faith.’[18] While this notion is not particularly new in the history of the Society, it is clear that there was an expressed need to reinvigorate this notion in the midst of larger historical changes.

This push for a more explicitly educationally driven mission was not occurring in isolation. Within the Society of Jesus, the 1960s were a period of significant reevaluation regarding the role of Jesuit education. General Congregation 31 (1965–66) had already formalized governance changes, including the recommendation that Jesuit universities establish governing boards with lay participation. This restructuring required a clearer articulation of institutional identity, which further necessitated the development of explicit mission language to ensure continuity between the Jesuit tradition and the increasingly complex realities of higher education.

Ratterman’s writings is symptomatic of the sentiment of the time, as he invokes the words of Michael P. Walsh, S.J. (1912–82), then president of Boston College, who stated, “The Catholic university should be, and must be in the future much more than it has been in the recent past, the place where the Church does its thinking.”[19] It is also evident in the sharp rise in institutional references to mission in 1968, when these discussions reached their highest recorded level in the JEQ. The phrase “the educational mission of the university” appeared frequently in this period, reflecting both the internal push within the Society and the external pressures of a rapidly evolving academic landscape. By emphasizing the university’s distinct mission, Ratterman and his contemporaries helped set the stage for the widespread adoption of mission statements in Jesuit universities in the following decades.

By 1970, the transformation of mission as an institutional concept was largely complete. Jesuit universities were no longer framed simply as participants in the Church’s apostolic mission; they were now seen as distinctive mission-driven institutions, responsible for carrying out their own apostolic work through teaching, scholarship, and engagement with contemporary societal challenges. This shift ensured that mission would remain a central guiding principle for Jesuit higher education, shaping governance structures, academic priorities, and institutional identity well into the future.

Mission as an Internal Disposition

Although mission as an internal disposition was the rarest category in the dataset, appearing in 26 instances (3.53%), its distinctiveness lies in how it framed mission not as a geographic identity or assignment, an institutional purpose, or an activity, but as an inwardly cultivated disposition or spirituality. This use of mission emphasized the formation of a mission-oriented mentality, reinforcing that being a missionary was not only about where one was sent but how one internalized and embodied certain qualities associated with Jesuit life and apostolic work.

One of the most consistent themes in this category was the cultivation of a “sense of mission,” a phrase that appeared in discussions of both Jesuit formation and student development. This sense of mission was not limited to formal missionary assignments but was framed as a guiding principle for how Jesuits and students alike should approach their work and responsibilities. The JEQ often referenced the “missionary character”, associating it with traits such as adaptability, dedication, and seriousness, reinforcing the idea that a Jesuit’s mission was not only an external task but also an internalized vocation.[20]

Several instances in the JEQ used mission metaphorically, describing a mindset of purpose and commitment rather than a physical mission territory. The term “missionary adaptation” was occasionally used to refer to the ability to adjust to new circumstances, whether in an explicitly missionary setting or in the broader apostolate of education and pastoral work. Similarly, the “seriousness of a missionary” was invoked to highlight the disciplined and focused approach expected of Jesuits and students, reinforcing the idea that mission was as much about personal transformation as it was about external evangelization.

Though less frequently employed, this rhetorical use of mission served an important role in shaping Jesuit identity and student formation. It helped frame Jesuit education itself as a formative process, instilling in students a disposition toward service, adaptability, and a higher sense of calling. While institutional discussions of mission would later dominate Jesuit education, the continued use of mission as a personal mentality and ethos ensured that the concept remained deeply embedded in the self-understanding of Jesuits and the educational culture of their institutions.

Mission within Titles or Names

The final category, accounting for 77 instances (10.45%), pertains to the use of mission in academic discourse, institutional references, and the titles of publications and organizations. This category highlights the intellectual and organizational dimensions of mission within Jesuit education, demonstrating how the term extended beyond apostolic identity and institutional purpose to function as a central theme in scholarly research and institutional culture.

During the period from 1938 to 1970, there was a noticeable expansion of scholarship on missions, reflecting a broader emphasis on the intellectual apostolate within Jesuit education. This shift aligned with the increasing professionalization of academia, the “publish or perish” mentality in higher education, and the Society of Jesus’ commitment to self-study and intellectual engagement. References in the JEQ frequently cited periodicals such as Jesuit Missions, Catholic Missions, and the New Journal of Missiology, illustrating the crossover between missionary work and academic inquiry. The rise of missiology as a field of study, particularly in Jesuit scholarship, positioned mission as both an object of research and a subject of theological and educational reflection.

The importance of scholarly engagement with mission was further institutionalized with the creation of the JEA and the JEQitself. The fact that the JEQ was founded as part of the JEA’s constitutions signals the rising centrality of scholarship and reflection in Jesuit educational governance. This demonstrates that, from its inception, the systematic study of Jesuit education was intertwined with discussions of mission, reinforcing the role of intellectual inquiry in shaping Jesuit identity and pedagogical philosophy.

By the 1950s, the term mission also appeared in references to student organizations, particularly mission clubs, as well as discussions about ‘mission movies’ to promote vocations.[21] These references highlight how missions remained embedded in the social and institutional fabric of Jesuit education, even as the meaning of mission evolved over time. The presence of mission-focused student groups suggests that, for many Jesuit institutions, mission was not just a theological or administrative concept but also a lived reality that influenced extracurricular activities, social engagement, and philanthropic efforts. Fundraising for missions in Jesuit schools in the United States was a recurring theme, illustrating that missionary work—whether abroad or in local communities—remained part of student imagination and institutional priorities.

The persistence of mission in academic and institutional titles reinforces its evolving but enduring role in Jesuit education. While earlier references in this category primarily focused on mission as an apostolic and scholarly subject, later instances indicate a more expansive view, integrating mission into the governance, student life, and intellectual output of Jesuit institutions. This category ultimately underscores how mission remained a multifaceted concept within Jesuit education, one that was continually interpreted, institutionalized, and engaged with across different domains.

The Shifting Landscape of Mission in Jesuit Educational Discourse

The analysis of mission in the JEQ from 1938 to 1970 reveals a changing discourse in Jesuit education, shifting from the idea of mission as an apostolic identity tied to geographical missions to an institutionalized concept embedded within Jesuit higher education. This transformation did not occur in isolation; rather, it reflects broader structural, theological, and educational changes within both the Society of Jesus and the global Catholic Church.

One of the most striking findings of this study is the decline of the traditional missionary identity in the JEQ, particularly after the mid-1960s. The concept of the missionary—once central to Jesuit self-conception—was increasingly replaced by a focus on Jesuit institutions as mission-driven entities. This reorientation aligns with key developments such as Vatican II’s emphasis on Catholic education, the expansion of Jesuit universities, and the shifting priorities of the Society of Jesus toward social justice and intellectual apostolates.

The quantitative data supports this transition. The apostolic identity category, which comprised the majority of occurrences before 1960, began to decline sharply in later years, while the category of institutional purpose saw a dramatic increase, peaking in 1968 with 39 recorded instances. This moment corresponds with a pivotal period in Jesuit education when university governance structures were changing, and mission was increasingly framed as a shared institutional responsibility rather than an individual calling.

This shift was not merely semantic. It reflected an ongoing tension within the Society of Jesus regarding its educational and apostolic priorities. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, discussions within the JEQ often reinforced a divide between the missionary and the educator, despite the fact that many Jesuits served in both capacities. The 1942 writings of Jesuit Calvert Alexander illustrate this tension, as he challenged the presumed distinction between missionaries and educators by pointing to American Jesuit missions in the Philippines and Baghdad, where nearly all Jesuits were engaged in teaching.[22] His argument, situated within the broader historical moment of World War II and post-war educational expansion, underscores the growing blurring of missionary and educational roles during this period.

By the early 1960s, however, this distinction was no longer the central debate. Instead, the focus shifted to Jesuit institutions as agents of mission, particularly as educational expansion required clearer institutional frameworks for governance, identity, and purpose. The language of mission in the JEQ increasingly emphasized universities as mission-oriented institutions, reflecting a broader trend in Catholic higher education where mission statements became tools of institutional coherence amid increasing lay participation and administrative formalization.

Furthermore, the integration of mission schools into the broader educational network of the American Assistancy in the 1940s and 1950s reinforced this trend. By bringing mission schools into dialogue with American Jesuit colleges and universities, the Society of Jesus facilitated a conceptual merging of the mission and the educational apostolate, which ultimately contributed to the rise of institutional mission language in later decades.

A parallel transformation occurred in how mission was understood in relation to intellectual life. The rise of publications on missiology and educational philosophy in the JEQ reflects a growing emphasis on the scholarly apostolate as an extension of the missionary enterprise. The Jesuit Paul Quay’s argument in the late 1960s—that the Jesuit scholar’s work is essentially the same as that of the Jesuit missionary—epitomizes this shift.[23] By equating intellectual labor with missionary work, Quay and his contemporaries effectively reframed mission as an academic vocation, reinforcing the idea that Jesuit universities themselves embodied the apostolic mission of the Society.

This institutionalization of mission discourse also coincided with structural changes in governance. The recommendation of governing boards for Jesuit universities during General Congregation 31 (1965–66) marked a significant departure from the older model in which educational governance rested primarily with Jesuit provincials and rectors. By transferring some degree of governance to lay administrators and faculty, Jesuit institutions were compelled to articulate their mission more explicitly, leading to a proliferation of mission statements in the second half of the twentieth century.

At the same time, the increasing use of mission statements in Jesuit higher education positioned these institutions within a larger cultural shift that extended beyond the Society of Jesus. By the 1970s and 1980s, the language of mission had been widely appropriated in corporate and managerial contexts, where mission statements became common tools for articulating organizational vision, values, and goals. Scholars such as Christopher D. McKenna have traced the corporate adoption of mission language to the rise of strategic management consulting, where institutions sought to codify their identity in competitive environments.[24] While Jesuit universities had already begun formalizing their own understanding of mission in response to internal governance changes, this corporate turn further shaped the way mission statements were deployed, often aligning with managerial frameworks for institutional planning.

Though the corporate influence on mission statements is not the primary focus of this study, its resonance with the institutionalization of mission language in Jesuit higher education suggests that the Jesuit conceptual shift preceded, but later intersected with, broader cultural and managerial trends. This raises questions about the extent to which Jesuit mission discourse adapted to, resisted, or influenced these corporate appropriations—a topic worthy of further exploration.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the shifting language of mission in the JEQ reflects a broader transformation in Jesuit education itself—one in which the Society’s apostolic focus moved from geographically defined missionary frontiers to include institutionally embedded educational missions.

Mission as a Framework for Jesuit Education

The transformation of mission within the JEQ from 1938 to 1970 illustrates a discursive shift that paralleled broader structural and ideological changes within Jesuit education. While mission remained a core term in Jesuit discourse throughout this period, its meaning evolved significantly. By the late 1960s, Jesuit universities were not simply places where missionaries were trained—they were understood as mission-driven institutions in their own right, carrying out the apostolic work of the Society through education, scholarship, and social engagement.

This shift did not signify the disappearance of the traditional missionary identity but rather a broadening of its scope. Even after 1970, Jesuits continued to work in overseas missions, often in regions historically associated with the Society’s apostolic expansion, including Latin America, Africa, and Asia. However, as governance structures within Jesuit universities became more formalized and lay participation increased, the institutional mission of education required clearer articulation. This led to the widespread adoption of mission statements, not only in Jesuit institutions but also across Catholic and secular higher education.

Yet, despite this institutionalization, the apostolic understanding of mission has not disappeared. Jesuit education today continues to engage with its missionary roots, not only through global educational initiatives but also through direct apostolic work in underserved communities. Contemporary Jesuit universities frequently emphasize their commitment to justice, service, and engagement with marginalized populations, echoing earlier mission-oriented priorities. In some ways, the expansion of Jesuit social and justice-oriented apostolates in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries represents a continuation of the missionary identity, though now applied in new ways—whether in urban outreach, refugee education, or advocacy for global justice.

This exploration of mission within the JEQ demonstrates that language is not static; it evolves in response to institutional needs, ideological changes, and cultural shifts. The trajectory of mission from 1938 to 1970 reflects a moment of transition—one that laid the groundwork for later articulations of mission in Jesuit education.

What remains clear is that mission continues to be a defining element of Jesuit identity, whether in its traditional form as an apostolic endeavor or in its institutionalized role as a guiding principle for education. The tension between tradition and adaptation that shaped the discourse of mission in the mid-20th century remains alive today, as Jesuit institutions continue to navigate their role in a rapidly changing educational and social landscape. Far from being a relic of the past, the concept of mission remains dynamic, contested, and deeply embedded in the evolving story of Jesuit education.

Notes:

[1] Charles L. Currie, S.J., “Some Distinctive Features of Jesuit Higher Education Today,” Journal of Catholic Higher Education 29, no. 1 (2010): 113–29.

[2] Association of Jesuit Colleges and Universities, “Characteristics of Jesuit Higher Education: A Guide for Mission Reflection” (Washington, DC: AJCU, 2021).

[3] The term mission carries a complex genealogy that extends beyond its ecclesiastical origins. In military contexts, mission has long referred to a clearly defined operational objective assigned to individuals or units, emphasizing strategic purpose and execution. This usage became particularly salient in the mid-20th century as Jesuit universities in the United States navigated the pre-, during, and post-war educational landscape. Many educational institutions saw a significant restructuring of their curricula due to wartime demands, government funding through the GI Bill, and Cold War-era strategic imperatives that aligned education with national security and technological advancement. The emergence of formalized mission statements in Jesuit higher education during the late 20th century parallels the broader corporate appropriation of the concept, as businesses in the 1970s and 1980s sought to articulate strategic visions through concise, value-laden declarations. This corporate turn in institutional rhetoric, which influenced universities as they faced increasing market pressures, coincided with Jesuit institutions’ own efforts to articulate their educational identity amid shifting cultural and financial landscapes. For an analysis of the corporate adoption of mission statements, see Christopher D. McKenna, The World’s Newest Profession: Management Consulting in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511511622; and for the evolving role of Jesuit higher education, see William P. Leahy, S.J., Adapting to America: Catholics, Jesuits, and Higher Education in the Twentieth Century (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1991); and Michael T. Rizzi, Jesuit Colleges and Universities in the United States: A History (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2022).

[4] For key texts on the educational philosophy and pedagogy of the early Society, see Cristiano Casalini and Claude Pavur, S.J., eds., Jesuit Pedagogy (1540–1616): A Reader (Chestnut Hill, MA: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 2016); Joseph de Jouvancy, S.J., The Way to Learn and the Way to Teach, ed. Cristiano Casalini and Claude Pavur, S.J. (Chestnut Hill, MA: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 2020); Francesco Sacchini, S.J., Exhortation and Advice for the Teachers of Young Students in Jesuit Schools, ed. Cristiano Casalini and Claude Pavur, S.J. (Chestnut Hill, MA: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 2021).

[5] The first series of JEQ was in print from 1938–70, until the JEA split into two different associations in 1970, one for the colleges and universities, and the other for secondary schools.

[6] For a historical analysis and English translation of the Instructio, see A. Taiga Guterres, “Articulating a Jesuit Philosophy of Education in the Twentieth Century: A Critical Translation and Commentary on the Instructio of 1934 and 1948,” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., 1, no. 1 (2025): 73–114, https://doi.org/10.51238/1ZnRn8z.

[7] The JEQ was incorporated as part of the official constitutions of the JEA.

[8] Many Jesuit colleges and universities in the United States trace their origins to mission schools established by Jesuit missionaries who were often exiled from their home countries following the various suppressions of the Society of Jesus in the late 18th and early 19th centuries even after Pope Pius VII formally restored the order in 1814. Jesuits played a crucial role in the expansion of Catholic education in the United States, frequently founding institutions in frontier regions or areas with growing Catholic immigrant populations. These early schools, such as Georgetown University (1789; English/Maryland Jesuits), Saint Louis University (1829; Belgian/Missouri Jesuits), Canisius College (1870; German/Buffalo Jesuits), and Santa Clara University (1851; Italian/California Jesuits), were initially conceived as extensions of the Jesuit apostolic mission, blending religious formation with classical education. Over time, they evolved into full-fledged universities while retaining their missionary ethos in service to Catholic education and intellectual life. For a detailed account of Jesuit educational expansion in the United States, see David J. Collins, S.J., The Jesuits in the United States: A Concise History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2023) and Rizzi, Jesuit Colleges and Universities in the United States.

[9] Calvert P. Alexander, S.J., “Proceedings of Annual Meeting, Jesuit Educational Association: American Jesuit Education is World-Wide: Developing a Mission Sense in Our Students,” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 5, no. 1 (1942): 53–60, at 53.

[10] The earliest occurrence of this in the JEQ was in 1947, when the Loyola School in New York discussed their annual fundraiser for the Jesuit Seminary Fund and Philippine Missions. A survey of Jesuit high schools from 1947–48 indicates that the average total mission collection per school was $1,590.48, totaling $44,536.10 for the missions from the 28 schools, which is worth almost $600,000 in the year 2025. See William J. Mehok, S.J., “Survey on Jesuit High School Faculty and Students: 1947–1948,” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 10, no. 4 (1948): 231–35.

[11] See for example, Alexander, “Proceedings of Annual Meeting.”

[12] See for example, William J. O’Malley, S.J., “Staying Alive in High School,” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 30, no. 1 (1967): 41–63.

[13] See for example, John W. Magan, S.J., “The Closed Retreat,” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 16, no. 3 (1954): 177–85.

[14] Wilfred Parsons, S.J., “Jesuit Research and Publication,” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 2, no. 1 (1939): 23–26.

[15] See for example C. J. Crusoe, S.J., “The Challenge of Our National Jesuit Institute,” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 28, no. 3 (1966): 193–202.

[16] See Crusoe, “The Challenge of Our National Jesuit Institute.”

[17] Ratterman served as the Vice President for Student Affairs at Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio.

[18] Patrick H. Ratterman, S.J., “The Vision of Christ and Christian Freedom: Part II—A Unique Educational Mission,” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 30, no. 2 (1967): 76–89.

[19] Michael P. Walsh, S.J., “Where Church and World Meet,” Catholic Mind 64 (December 1966): 43–48

[20] The emphasis on cultivating a “mission spirit” was not limited to the JEQ but was echoed in other Jesuit periodicals of the time. For example, Jesuit Missions, a magazine of ‘apostolic endeavor,’ frequently reinforced the idea that education should instill a form of mission zeal in students. See, for instance, a short editorial note in Jesuit Missions that highlights the necessity of fostering a missionary disposition in students through education, encouraging them to internalize the missionary ethos even if they were not formally destined for the mission field. This broader emphasis on mission-minded formation reflects the Jesuit commitment to shaping individuals who viewed their education and professional work as part of a larger apostolic mission. “The School—The Missions,” Jesuit Missions 7, no. 8 (September 1933): 182.

[21] See “News from the Field,” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 19, no. 4 (1957): 247–53; and Woodstock Committee, “Vocations in Our High Schools,” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 21, no. 1 (1958): 42–53.

[22] Alexander, “Proceedings of Annual Meeting.”

[23] Paul M. Quay, S.J., “Jesuit, Priest, and Scholar: A Theory of our Learned Apostolates,” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 28, no. 2 (1965): 98–121.

[24] See McKenna, The World’s Newest Profession.

Alexander, Calvert P., S.J. “Proceedings of Annual Meeting, Jesuit Educational Association: American Jesuit Education is World-Wide: Developing a Mission Sense in Our Students.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 5, no. 1 (1942): 53–60.

Association of Jesuit Colleges and Universities. Characteristics of Jesuit Higher Education: A Guide for Mission Reflection. Washington, DC: AJCU, 2021.

Casalini, Cristiano, and Claude Pavur, S.J., eds. Jesuit Pedagogy (1540–1616): A Reader. Chestnut Hill, MA: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 2016.

Collins, David J., S.J. The Jesuits in the United States: A Concise History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2023.

Crusoe, C. J., S.J. “The Challenge of Our National Jesuit Institute.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 28, no. 3 (1966): 193–202.

Currie, Charles L., S.J. “Some Distinctive Features of Jesuit Higher Education Today.” Journal of Catholic Higher Education 29, no. 1 (2010): 113–29.

Guterres, A. Taiga. “Articulating a Jesuit Philosophy of Education in the Twentieth Century: A Critical Translation and Commentary on the Instructio of 1934 and 1948.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., 1, no. 1 (2025): 73–114. https://doi.org/10.51238/1ZnRn8z.

Jouvancy, Joseph, S.J. The Way to Learn and the Way to Teach. Edited by Cristiano Casalini and Claude Pavur, S.J. Chestnut Hill, MA: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 2020.

Leahy, William P., S.J., Adapting to America: Catholics, Jesuits, and Higher Education in the Twentieth Century.Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1991.

Magan, John W., S.J. “The Closed Retreat.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 16, no. 3 (1954): 177–85.

McKenna, Christopher. The World’s Newest Profession: Management Consulting in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511511622.

Mehok, William J., S.J. “Survey on Jesuit High School Faculty and Students: 1947–1948.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly10, no. 4 (1948): 231–35.

“News from the Field.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 19, no. 4 (1957): 247–53.

O’Malley, William J., S.J. “Staying Alive in High School.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 30, no. 1 (1967): 41–63.

Parsons, Wilfred, S.J. “Jesuit Research and Publication.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 2, no. 1 (1939): 23–26.

Quay, Paul M., S.J. “Jesuit, Priest, and Scholar: A Theory of Our Learned Apostolates.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 28, no. 2 (1965): 98–121.

Ratterman, Patrick H., S.J. “The Vision of Christ and Christian Freedom: Part II—A Unique Educational Mission.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 30, no. 2 (1967): 76–89.

Rizzi, Michael T. Jesuit Colleges and Universities in the United States: A History. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2022.

Sacchini, Francesco, S.J. Exhortation and Advice for the Teachers of Young Students in Jesuit Schools. Edited by Cristiano Casalini and Claude Pavur, S.J. Chestnut Hill, MA: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 2021.

“The School—The Missions.” Jesuit Missions 7, no. 8 (September 1933): 182.

Walsh, Michael P., S.J. “Where Church and World Meet.” Catholic Mind 64 (December 1966): 43–48.

Woodstock Committee. “Vocations in Our High Schools.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 21, no. 1 (1958): 42–53.

- Title: ‘Mission’ in (Con)text: A Philological Examination of Its Shifting Role in Jesuit Educational Discourse

- Author: Antonio Taiga Guterres

- Article Type: Research Article

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.51238/Tv5vs7H

Language: English - Pages: 255–272

- Keywords: mission; mission statement; Jesuit Educational Quarterly; Jesuit Educational Association

- In: Jesuit Educational Quarterly

- In: 2nd ser., Volume 1, Issue 2

- Received: 29 July 2024

- Accepted: 05 August 2024

- Publication Date: 28 April 2025

Last Updated: 28 April 2025 - Publisher: Institute of Jesuit Sources

- Print ISSN: 2688-3872

- E-ISSN: 2688-3880

APA

Guterres, A. T. (2025). ‘Mission’ in (con)text: A philological examination of its shifting role in Jesuit educational discourse. Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 1(2), 255–272. https://doi.org/10.51238/Tv5vs7H

CMOS

Guterres, A. Taiga. 2025. “‘Mission’ in (Con)text: A Philological Examination of Its Shifting Role in Jesuit Educational Discourse.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., 1, no. 2: 255–272. https://doi.org/10.51238/Tv5vs7H.

MLA

Guterres, A. Taiga. “‘Mission’ in (Con)text: A Philological Examination of Its Shifting Role in Jesuit Educational Discourse.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., vol. 1, no. 2, 2025, pp. 255–272. https://doi.org/10.51238/Tv5vs7H.

Turabian

Guterres, A. Taiga. 2025. “‘Mission’ in (Con)text: A Philological Examination of Its Shifting Role in Jesuit Educational Discourse.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., 1, no. 2: 255–272. https://doi.org/10.51238/Tv5vs7H.

© Institute of Jesuit Sources, Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, All Rights Reserved