Research Article

Circa Missiones: Jesuit Understandings of Mission through the Centuries

Section 2. Asia

Jesuit Procurators and the East Asian Missions in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century: Material Cultures in Motion

Reis Pereira, Diogo. “Jesuit Procurators and the East Asian Missions in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century: Material Cultures in Motion.” In “Circa Missiones: Jesuit Understandings of Mission through the Centuries (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Lisbon, Portugal, June 12–14, 2023),” ed. Alessandro Corsi, Claudio Ferlan and Francisco Malta Romeiras, special issue, International Symposia on Jesuit Studies 3, no. 1 (2025): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2023.11.

[1] The office of Procurator is of such great importance in Japan that he is the second person in the province, on whom everyone depends because all the houses are provided with his procuradoria; hence, the procurator must be a person of many parts.[2]

These were the terms in which the visitor of the missions of East Asia, Fr. Francesco Pasio (1554–1612), justified the appointment of Fr. Carlo Spinola (1566–1622) to the office of procurator of Japan in a letter addressed to Claudio Acquaviva (1554–1615), superior general of the Society of Jesus (in office 1581–1615), in 1612. A missionary with a remarkable background in the field, Spinola thus became the main bridge between the Society’s spiritual objectives and the temporal conditions that needed to be ensured. It was on this path, marked by intrigue, power plays, and intercontinental networks, that Spinola remained in office until he was imprisoned in 1618,[3] against his personal wishes, as he considered the post “repugnant” and unfit for a priest.[4]

This emphasis on the figure of the procurator is not, however, a novelty that arose with this particular episode. In fact, documentary sources reveal that throughout the Portuguese assistancy, between the late sixteenth century and the second half of the eighteenth century, procurators occupied a prominent position in the Jesuit hierarchy. On May 19, 1625, Fr. Jerónimo Rodrigues (1567–1628), visitor of China and Japan, wrote to D. Francisco de Mascarenhas, captain general of Macao between 1623 and 1626, following a letter he had received from the scribe Mateus da Costa. In it, Rodrigues argues that the procurator of Macao, Fr. João Rodrigues Tçuzu (c.1561–1633), should accompany the delegation of elected citizens who were going to meet the dutang or vice-king of the Guangdong/Guangxi provinces, to discuss “business of greater importance, which for years or never have been offered to this city.” Arguing the value of the business for the “conservation of this land, and the lives of all” and for the “continuation of these three principal Christendoms [of] Japan, Cochinchina, and China,” the visitor points out that the procurator is desired by the envoys, “showing great difficulty in going without him, so as to help them in the spiritual, [but especially] to be able to give them some light in the business they will be dealing with.” In addition, he emphasizes the procurator’s great abilities “due to his extensive experience and intelligence of Chinese affairs, having been in the region for more than forty years, and having been in the two courts [of] Nanking and Pekin,” which will certainly guarantee a positive outcome of the negotiations.[5]

Indeed, interpreting the figure of procurator, who played a fundamental role in the financing of the missions, has always been a difficult task, with sources clearly revealing the multiplicity of functions in his charge as well as his centrality and power and the influence he wielded. Based on an analysis of letters, descriptions, and regulations/ instructions,[6] it is possible to define an “ideal profile” for procurators that distinguishes them from all other missionaries. This distinction lies primarily in the tasks assigned to them as agents who ensure the temporal maintenance of the order. Naturally, an “ideal procurator” should be competent and completely dedicated to his office. Endowed with skills in the field of communication and versed in local languages, the procurator had to be able to act under pressure, in multiple scenarios, and to have experience in business and the respective know-how; it was also necessary to have an understanding of the various markets and to be part of formal and informal trade networks, thus facilitating structural partnerships with merchants, as well as the accounting and administrative skills necessary to keep detailed records of all operations. Discipline, obedience to the established hierarchy, prudence, and versatility were crucial traits. A reliable man for the order, the procurator was required to keep the “secrets” of the trade—for example, Rodrigues Tzuçu highlights the monetary benefits behind the secrets that Japanese procurators must keep about the practice of silver smelting in Japan—and to be extremely persistent given that it was “a painful job because distrust is followed by infinite dislike of the position.”[7]

Although the procurator’s work was decisive to the functioning of the missions and, in the case of the province of Japan and the mission/vice-province of China, had its own unique dynamic, the lack of academic interest and various knowledge gaps that mark this field of work must be stressed. Whereas the subject of procurators has been duly explored in the case of the Spanish assistancy—see for example the works of Felix Zubillaga[8] and Agustín Galan-García[9]—the same cannot be said for the Portuguese assistancy; indeed, only the procurators of Brazil and Maranhão have been targets of systematic studies, with prominence inevitably on the name of Serafim Leite (1890–1969).[10] It is only since the 1990s that historiography has paid due attention to the procurators of the East Asian missions. In this area, it is worth mentioning both the work of Dauril Alden,[11] who opened the field of study on procurators, listing their various typologies and associated functions, and the doctoral thesis of João Paulo Oliveira e Costa,[12] which identifies Japan’s procurators and their support networks at the turn of the seventeenth century during the government of Bishop D. Luís de Cerqueira (in office 1598–1614). In line with Costa’s studies, the Bulletin of Portuguese/Japanese Studies of CHAM—Centro de Humanidades—published a set of issues that include case studies on procurators in China and Japan.[13]

In the Atlantic context, J. Gabriel Martínez-Serna provided evidence of the procurators’ crucial importance to the work of the Society of Jesus,[14] specifying the institutional contours of the position in the order’s administrative structure. Charles Borges[15] and Fred Vermote[16] stand out for highlighting the procurators’ central role in the missions’ finances, noting again their accounting responsibilities in the overall management of the provinces’ economic and financial structure. Finally, Hélène Vu Thanh and Ines G. Županov have described the multifaceted role of the procurator, especially in Nagasaki and Macao,[17] bringing the local particularities of the office into dialogue with the Society’s global dynamics. In recent years, the study of procurators has emerged as a topic of scholarly interest for Portuguese historians, namely Isabel Murta Pina and Maria João Pereira Coutinho.[18]

This article is divided into four parts. Following a discussion of the nature of the research, the second part of the article, “Jesuit Procurators: Typologies and Functions,” presents the diversity of the procurators who held the office, with an in-depth analysis of their position in the Jesuit hierarchy, and demonstrates the range of their charges. The third, “Procuraturas as Workspaces: Business and Materialities on a Global Scale,” uses unpublished documentation to examine the workplaces of the procurators—procuratura (or “procure”)—through a comparative study of the structure found in Macao with that of Lisbon. The fourth and final part, “Networks and Material Culture in Motion between Lisbon and East Asia: Procurators of the Missions in Action (1613–56),” focuses on the general procurator based in Lisbon, more specifically on the network of procurators linked to this figure and their economic dimensions but also their role in the circulation of missionaries, products, and money at the intercontinental level in the first half of the seventeenth century.

Nature of the Research: Objectives, Approach, and Methodological Paths

My objective is to further our understanding of a group of Jesuits—the procurators— who have remained on the margins of history. Therefore, efforts are made to identify their support networks, clarify their relationships with merchants, and to study their role in trade at the local, regional, and global levels, which was essential to ensure the functioning of the missions and the missionaries’ livelihood. It is also essential to recognize the ethical issues these agents faced as religious men in an economic and material position. To this end, I not only recognize the historiographical production on the theme but also rely on an extremely promising set of documentation—the records of accounts, expenses, and operations kept by the general procurators based in Lisbon. Although most of these are located in the ARSI’s (Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu) “Japonica Sinica,” “Lusitania” and “Goa” collections, I have in fact been able to recover a set of complementary data, previously dispersed, by cross-referencing research in the archives of Lisbon: AHU (Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino), BNP (Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal), and BAJA (Biblioteca da Ajuda, collection “Jesuítas na Ásia”).

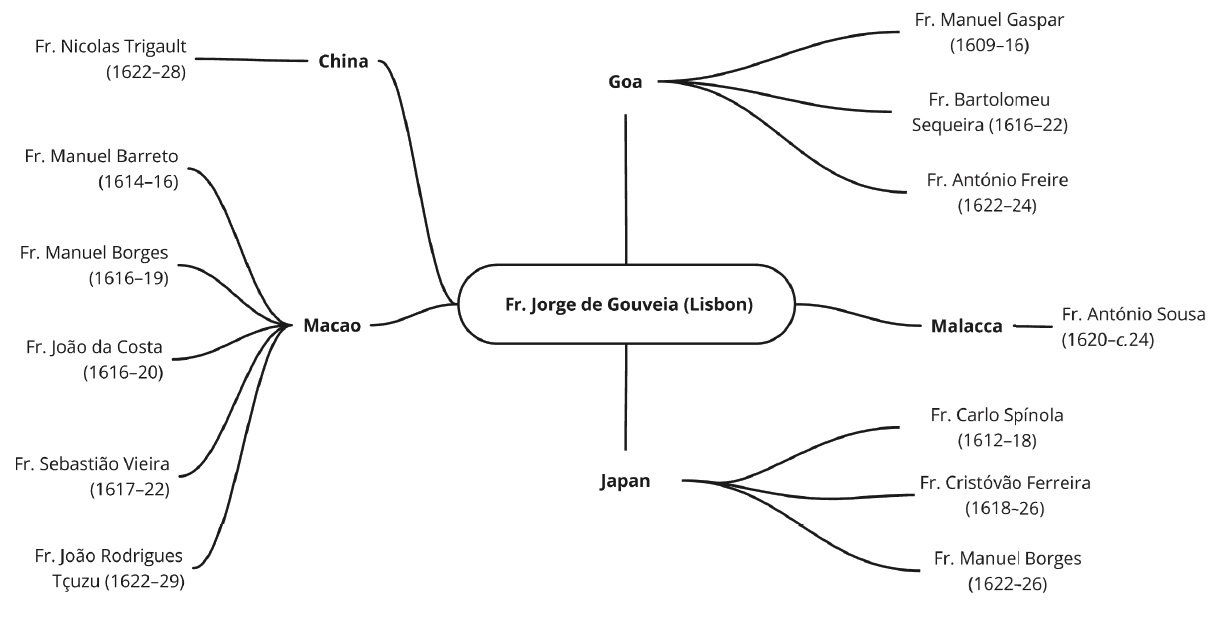

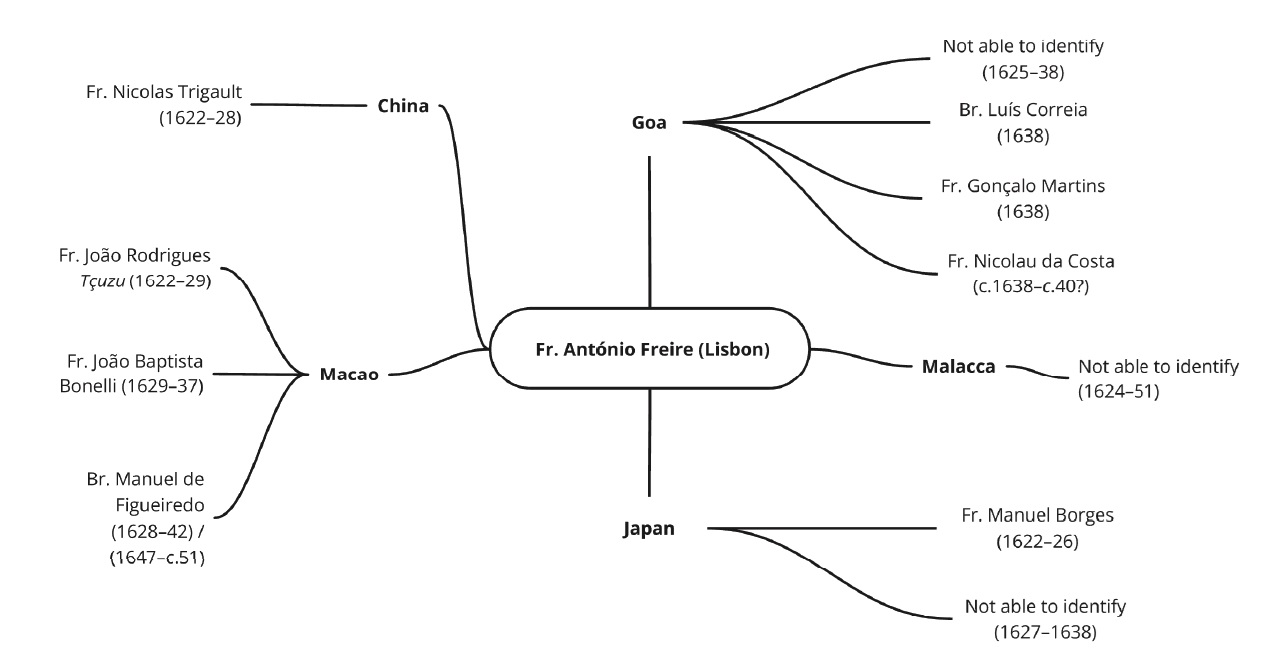

On the other hand, the nature of this research can only be truly understood if we recognize the methodological path that has provided theoretical support for the positions taken, namely through the use of “network analysis” and “global microhistory.” Their achievements can be seen, above all, in terms of the visual representation of the networks of procurator under study, the research in three dimensions—putting the local and regional particularities in dialogue with the global dynamics of the Society— as well as in the attempt to overcome the traditional marks of history and to identify new lines of work like the topic of corruption associated with the movement of money and goods. More specifically, using the theoretical foundations of global microhistory, I start from the careers of Fr. Jorge de Gouveia (in office 1613–26) and Fr. António Freire (in office c.1626–c.1656) in the Lisbon procuratura to define the network of procurators (see figures 1 and 2) to which they belonged and how they influenced it at the transoceanic level. Furthermore, supported by the assumptions suggested by “network analysis,” I seek to understand the dynamics of this intercontinental relationship and to study the active and conscious bond of these procurators with the non-linear phenomenon of the first phase of globalization, especially through the material culture put into circulation.

Jesuit Procurators: Typologies and Functions

The Society of Jesus was undoubtedly “one of the most dynamic religious corporations in the early modern world.”[19] An analysis of the intense Jesuit campaigns that went from the European stage to an unprecedented overseas proliferation—with a total of twenty-one provinces and vice-provinces in 1579[20]—in a matter of forty years implies a renewed vision of the action of these missionaries “beyond regional campaigns to raise money and transoceanic requests to royal patrons,”[21] distinguishing them as active agents in a multipolar network of contacts, flows of people, and of material and scientific transfers. Although missionary work was directed toward a single and common goal, namely the spread of Catholicism, the Jesuits quickly revealed an awareness of the spiritual limits imposed on them by the economic, financial, and material demands of the lands in which they operated, especially in those places with little or no colonial and military power.

Therefore, and as stressed by Luke Clossey, the line of study focusing on the religious mission in the modern period should not overlook their financial and economic dimension, which was fundamental to the subsistence of both the missionaries and the missions themselves.[22] Moreover, it should be noted that the Society hierarchy had never ignored this sphere of work, which proved so important from the outset that the post of procurator was created by Ignatius of Loyola and his followers; not only was the procurator given responsibility for the order’s economic affairs but he also had to adapt “the religious rules of the Society and the material needs of its ministries to the political and economic realities of the secular world.”[23] However, although this remit was one of the “more complex in the terminology of the Institute due to the different uses that were and still are made of it,”[24] there are few remaining references to the procurator’s functions in the legislative body of the order (Constitutions); indications are made only to court procurators and college procurators and do not cover the multifaceted typology of procurators over the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[25]

Like the organizational configuration of the Society of Jesus, with its pyramidal structure and centralized administration,[26] the procurators also operated within a top down hierarchy, with some acting mainly in the diplomatic field (such as the court procurators) and others involved in the field of business, finance, and the transfer of products, people, and money on a global scale. This relationship between the temporal and spiritual power, which strongly marks the order, is especially visible in the East Asian missions. Thus, although there are different types of procurators, this article focuses on three of the types that make up the network under analysis, primarily their performance in the financial and economic fields, but also in the field of the circulation of material culture. More specifically, and as listed by Dauril Alden,[27] these are the procurators “(i) of the missions, (ii) those of the provinces or vice-provinces and (iii) those of the colleges or residences.”[28]

The position of procurator of the missions was established in the early 1570s and was headquartered in Lisbon in the Portuguese case and Seville in the case of Spain. These Jesuits, particularly those in charge of the missions in China and Japan, performed a wide variety of roles and were instructed by their superiors as to how to conduct their operations and how to act. The two memorials sent by Fr. Alessandro Valignano (1539–1606) to the procurator of the missions in 1574 and 1587 respectively stand out as they summarize his actions.[29] Regarding sea voyages, they were responsible for organizing and coordinating all the logistical apparatus inherent to sending missionaries to the missions, ensuring it was perfectly articulated “with the calendars of departure and arrival of the ships at the port of Lisbon.”[30] They were also in charge of assuring the accommodation of arriving missionaries and meeting their needs, as well as requesting viaticum and ensuring the materials required by those who left; the detailed records of Gouveia and Freire as procurators outline this process.[31]

According to the guidelines sent by Valignano, the administrative control of the papers relating to the procuratura was also a key part of his duties; it involved ensuring the correspondence was sent and received “well and safely with their brands,”[32] but also that all operations, expenses, revenues, and relevant financial data on the movement of the province’s money were recorded in his accounting books. Bearing in mind that meeting the demands of administering all the missions of the Portuguese assistancy was beyond any one person alone, a multiplication policy of procurators was implemented according to the geographical areas of the missions between the end of the sixteenth and the start of the eighteenth century. Indeed, at an advanced stage, I found a total of five procurators of missions in Lisbon, one for each province: Brazil, Maranhão, Goa, Malabar, and one for China and Japan.[33]

Linked to this typology, there was a network of provincial and vice-provincial procurators at the transoceanic level—Goa, Malacca, Macao, and within the missions of China and Japan—with a similar volume of work, as Fr. Manuel Borges (1583–1633) points out in a letter to Superior General Muzio Vitelleschi (1563–1645, in office 1615– 45).[34] For the missions, it was essential that his network communicated effectively and that administrative and economic problems were resolved quickly. However, like the mission procurators, the provincial procurators had a busy schedule and, according to Alden, were most likely “submerged in working papers.”[35] Although all the functions were of great importance and warranted due attention, the unique contours that this type of procurator would acquire in Macao, China, and Japan should be highlighted, described by Rodrigues Tçuzu as “pure negotiator, [and for that] he is very different from that of the other provinces: he needs different talents, different orders, […] other-wise this province, which depends so much on the temporal [power], and this depends so much on the procurator, will always suffer a lot.”[36]

To complete this network of procurators between Lisbon and East Asia, mention should be made of the work carried out by the college procurators. While this type of procurator is different from the two typologies mentioned as their action was con- fined to Jesuit residences, it was again clear that many demands were made on them in terms of the economic affairs of the respective colleges. As such, they supervised “the activities of their staff, including cooks; cleaning personnel; the ostiarius or porter (porteiro), who was a guard, doorkeeper, and sometime janitor; the infirmarian; and the buyer. They also kept inventories of supplies on hand and personnel records.”[37] Finally, as Isabel Pina points out, they were also in charge of channeling funds to and from the provincial/vice-provincial headquarters.[38]

Procuraturas as Workspaces: Business and Materialities on a Global Scale

All the above-mentioned activities took place in the space of the procuratura, the procurator’s official and formal place of work, from which he coordinated the financial and administrative affairs related to the vice province of China and the province of Japan. Understanding these spaces, how they were structured, and the centrality they acquired in the business and material transfers made by these agents is a completely distinct field of work that is inextricably linked to the study of the procurators that I have devoted much attention to during my ongoing research. Yet again, it was the primary sources that allowed me to collect a set of unpublished data that illustrate how the procuraturas of Macao and Lisbon were configured in the first half of the seventeenth century.

On August 31, 1616, the father procurator of Japan, Manuel Barreto (1563–1620), ceased his duties in Macao and was replaced by the newly appointed Borges. As yet, little is known about how such changes in the procuratura took place, especially in terms of whether they involved any kind of training process for those newly appointed to the position. Nevertheless, with regard to the transition from Barreto to Borges, the first took great care to leave his successor a memorial in which he provided a detailed description of the configuration of the procuratura, the objects that belonged to it, and some of the names of the Macanese community linked to its functioning, as well as a lengthy description of the offices that belonged to the procurator of China and Japan.[39] These two offices were located inside the College Madre de Deus, along with a cubicle that had belonged to Visitor Francesco Pasio, which was duly interconnected by a corridor where products were stored. The memorial, which has already been included in other works, notably that of Noël Golvers,[40] demonstrates the central importance of this structure and its broad scope. It was there that they planned work schedules and strived to meet them, wrote letters, balanced the books, received merchants, and concluded deals; but it was also where an intense and unique cultural exchange between East Asia and Europe took place. It should be noted from the outset that the space was full of products not only related to spiritual work (e.g., “seahorse” rosaries, and “black bread from India,” veronicas, reliquaries of various origins, and sacras printed in Japan and Portugal) but also medicinal products (bezoar stone), office supplies (Japanese feathers and different types of paper), as well as the many books that belonged to the procuratura.[41] Basically, products from all over the African, European, and Asian continents could be found there, attesting to the global dimension of the functions of the East Asian procurator.

On the other hand, the detailed description in the memorial shows that the procurators’ offices were at the heart of this organization. Again, Barreto emphasizes the diversity of products in transit to the different missions and tells of the wide range of work documents that could be found on the desks of the procurators. More specifically, he focuses on the “three drawers under the big office of white wood.” He explains that the first contained documents related to deeds, properties of the Society, lists that contemplate the house rentals, and also the regimento for the procurator. The second contained letters concerning business and administrative sentences, wills, and even associated letters to Bishop Cerqueira. Finally, papers on the silver business from the time of Father Procurator Miguel Soares (in office 1588–1600) could be found in the third drawer.[42]

In general, Barreto portrays the procuratura as a fundamental space in the context of the East Asian missions. However, located within the College Madre de Deus until 1620, it was a point of contention between the procurators and other Jesuits due to the nature of its affairs and the influx of Chinese merchants to the college,[43] where the spiritual structure was not differentiated from the temporal activities of the Society of Jesus.[44] As a result, we know that the procuratura went through a transition process in the early 1620s, led by the procurator in office, Fr. Sebastião Vieira, and was transferred to a space outside the college. This spatial transition, as well as the configuration of the new procuratura of Macao, is described in a letter from Fr. Gabriel de Matos (c.1571–1634) to Superior General Vitelleschi.[45] Critical not only to the procurator’s power and the centralization of decision-making in him but also the sums of money employed, it states that “the interior of the new building measured 120 spans in length and forty-eight spans in breadth, and its solidly constructed walls were five spans thick. The five principal rooms all faced south onto a small garden with a well and their windows were protected by stout grills.”[46] Finally, Matos also remarks on the cubicles of the procurator and the brother who assists him, revealing that they are “larger than those of the assistants,”[47] and criticizes the stores associated with the structure of the procuratura, indicative of their business activities.

On the other side of the world, Gouveia also provides us with information on the configuration of the procuratura in Lisbon in his summary of the accounts of his period as procurator of the missions, which was sent to Rome on April 25, 1626.[48] Of particular prominence in Lisbon were the College of Santo Antão-o-Novo, “place of residence of the general procurator,”[49] and the store of the procuratura, based in Beco dos Açu- cares, more specifically in the Remolares area,[50] currently Cais de Sodré. Considering Lisbon’s seventeenth-century topography, it was a relatively short distance between the procurator’s residence and the store where he conducted business for the East Asian missions. These two core areas of the procurator’s action were duly articulated with other parts of the city, reflecting the cosmopolitanism of Lisbon at the time.

The procuratura lodge was located in a strategic position, and this was where the procurator handled financial affairs related to the province of Japan and vice province of China. To the west, the lodge’s proximity to the Boavista area, where fleets heading to the overseas missions anchored, allowed the procurator to deal rapidly with the arrival and departure of products and missionaries. On the opposite side, the lodge was close not only to other places of the Jesuit leadership, such as the Church of São Roque, but also to the main areas of commerce, such as Terreiro do Paço, Casa da Índia, the customs and other warehouses, and establishments essential to the economic and financial nature of the procurator’s functions.[51]

Generally, the centrality of the procuratura of Lisbon was similar to that of the procuratura of Macao. First, it was full of goods for the missions such as “partisans, coffins, bolts,” “wine, meat, oil, fish, candies, chickens, and vegetables” for the missions, but also various utensils to ensure the supply of the missionaries (clothes, veronicas, breviaries, and books).[52] It was probably also where accounts were done for the respective missions, in this case the money from China and Japan, and where the procuratura’s properties in the city were managed. The most emblematic case mentioned by Gouveia is the disputes surrounding Quinta de Carcavelos, one of the most profitable sources of income for the mission in Japan.[53] Although we have no information about the institutional evolution of the procuratura, Gouveia’s records state that the shop, which had been rented, was formally acquired in 1621;[54] this must have remained the case until 1668, when the area was profoundly altered by royal decree and a series of alleys were closed, including the Beco dos Açúcares.[55]

To summarize, we can see from the procuraturas established in both Macao and Lisbon the intense dynamics linked to the procurator’s work. The study of these structures also sheds light on their strategic positioning and the many fields in which they operated, both in business and in deep cultural and scientific exchange, thus revealing themselves to be institutions of a truly global nature.

Networks and Material Culture in Motion between Lisbon and East Asia: Procurators of the Missions in Action (1613–56)

The importance of the Jesuit procurator’s work in the social, cultural, and economic exchanges of the seventeenth century must be considered in the context of the increasingly globalized world marked by wide channels of communication, shortening distances, and the approximation of different communities.[56] Both the articulation networks, especially the networks of procurators, and the circulation of material are practical testimonies of the vast geography of the missions and their interaction with the growing global trading system and demonstrate the connectivity of cultures and the sharing of both knowledge and technology,[57] above all through the moving material culture that profoundly transformed the world of the modern era.[58]

In the first half of the seventeenth century, the transit of products and people to the geography of the East Asian missions was intense. The significant number of ships (more than fifty) and hundreds of missionaries who left Lisbon for the Indo-Pacific territories between 1600 and 1650 suggest that these missions were among the most attractive destinations for missionaries.[59] Thus, it is not surprising that a network of mission, provincial, vice-provincial, and college procurators was established at the start of the century between Lisbon, Goa, Malacca, Macao, and Japan with the aim of making the missionary activities practiced in Sino-Japanese territory financially viable.

How was this network of procurators identified? First, through the information collected from the bibliographic set mentioned above, notably Alden’s pioneering work and his effort to identify the main headquarters of the procuraturas throughout the Portuguese assistancy.[60] Second, through analysis of the set of primary sources collected during the research, especially those based on the Society’s catalogs and through the procurators’ accounting books (or what is left of them). It should be noted that despite frequent “references to the sheets of accounts and other records made by procurators” in the Jesuit documentation of this period,[61] and exceptional cases, such as the accounting book for Fr. François De Rougemont (1624–76),[62] most of these records are missing. More than simple summaries of the financial situations of the provinces, the accounting books were indispensable to identify the various operations conducted by the respective procuratura and, for the historian, are a fundamental record of the patronage and support networks of these Jesuits in the different parts of the world. In this context, I believe that the documentary core based on the accounts, operations, and records of procurators is an open field of research, which I am currently exploring in my doctoral research.

Based on both catalogs and account records, I have so far identified around twenty-one individuals who assumed the position of procurator in the first half of the seventeenth century, duly assigned to procuraturas that were dispersed across geographical areas. These missionaries, destined to uphold their vows of poverty and to work as guarantors of the patrimony and financing of the missions of China and Japan, became key figures in these provinces. Indeed, on January 28, 1624, Rodrigues Tçuzu himself said that the method of evangelization at that time was very different from the early church.[63] Precisely along this line of thought, Borges stressed in 1618 that the office of procurator was not even associated with the religious state, arguing to the superior general that a more flexible approach should be taken by the superiors so that the procurators could overcome the material and supply difficulties felt in those missions.[64]

On the other hand, these and other records associated with the accounts of the procuratura reveal the attempts made to improve material conditions in the missions of East Asia. In the case of Lisbon, we see a constant sending of food products, utensils, books, papers, letters, religious instruments such as breviaries, crucifixes, and veronicas, and money when Gouveia and Freire were in office.[65] From Macao, Borges also attests to a continuous circulation of products, not only from Lisbon (most likely sent by Gouveia himself) and India but also from the triangle of trade between Macao, mainland China, and Japan. The most emblematic case is that of his records from the year 1618, where he deals with an order of twenty coffins, distributed by six ships that went from Macao to Japanese territory,[66] where the mission was steadily weakened after the edict of 1614.

Figure 1. Network of procurators of the East Asian missions during the period in office of Fr. Jorge de Gouveia in Lisbon, 1613–26. Diagram made by the author.

Figure 2. Network of procurators of the East Asian missions during the period in office of Fr. António Freire in Lisbon, 1626–56. Diagram made by the author.

The document provides a detailed description of the order and what we would find in each chest, such as “chest number eighth: sixty-seven very good Nankim cermesin skirts […]”;[67] the detail of the information is interesting as it indicates due reflection on the expenses incurred and includes a “list of the prices of the things that are sent for supply in July 1618,” and, therefore, the fixing of the prices of the various items.[68] It demonstrates the usefulness of the know-how of the procurators, their experience in the field of business, and their close contact with the merchant community and even with the markets themselves (such as the Canton fair).

Finally, also during Freire’s long period heading up the Lisbon procuratura, there was intense activity related both to the circulation of material for the missions and to the sending of missionaries to the provinces. Over a period of thirty years, the work was marked by the need to adapt to the political changes that took place not only in Portugal (with the restoration of independence in 1640) but also in Japan (with the definitive closure of the mission in 1639) and China (with the Ming–Qing dynastic transition in the 1640s and 1650s).

Nevertheless, these conjunctures did not alter Freire’s vision and objective of ensuring the continuation of evangelizing activities in East Asia. Although he lamented the difficulties experienced due to the political panorama and the Dutch and English attacks on Portuguese ships that conditioned trade and the sending of missionaries to the East, he demonstrated the necessary resilience to fulfil his responsibilities.[69] His work in the logistical operations for the missionaries heading to the China and Japan missions should therefore be underlined. The case of the process he organized for fathers “namely Jacinto Vandri, Francisco Adrodato and Martino Martines,” who arrived in Lisbon in 1640 from the College of Coimbra with the aim of embarking for the East- ern missions, is an example of this work.[70]

Conclusion

The procurator was undoubtedly a key player in all the activities of the Society of Jesus, ranging from the continued presence in the overseas territories to sending both its workforce (missionaries) and the provisions they needed. Moreover, the close contacts with Chinese and Japanese civil servants during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries exemplifies their influence with the local authorities. The broad scope of the work of the procurator described in this article is substantiated in the following description given by Fr. João Rodrigues:

Procurator, and moreover purchaser and steward, and all other offices pertaining to the temporal, and also merchant in the form granted; for he seeks the food and sustenance of the whole province, with what comes from India, with contract from Japan, and with loans and alms, he sends out those who come and go, and provides them with all the necessities of their persons, as well as spiritual things for Christendom.[71]

The Jesuit procurator is a complex and challenging office due to the nature of its functions and the number of responsibilities he was entrusted with. He was undoubtedly one of the most important agents of the missions and yet one of the most neglected by historiography. In line with the accommodation policy, these missionaries needed to be endowed with linguistic skills, social and cultural instruction, business and administrative experience, as well as leadership skills so that they could coordinate institutions with the work of the procuratura.

This article aimed to demonstrate the importance of these missionaries at the local, regional, and global level of the Society of Jesus, and to draw attention to this extremely promising field of study. The procurators played a pivotal role in the administration of the missions of East Asia; without them, the intercontinental dimension the order achieved in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries would have been impossible.

Notes:

[1] Scholarship holder at Macau Scientific and Cultural Center (CCCM). This work was supported by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P. by project PRT/BD/154848/2023 and DOI https://doi. org/10.54499/PRT/BD/154848/2023. Integrated researcher at CHAM—Center for the Humanities, in the Environment, Interactions, and Globalization research group.

[2] Letter from Visitor Francesco Pasio to Superior General Claudio Acquaviva, March 15, 1612, fol. 139, 15 [I], Japonica-Sinica, Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu.

[3] Josef Franz Schütte, Monumenta historica japoniae I: Textus catalogorum japoniae aliaeque de personis domibusque S.J. in Japoni informationes et relationes, 1549–1654 (Rome: Monumenta Historica Societatis Iesu, 1975), 553.

[4] Daniele Frison, “‘El officio de procurador al qual aunque tengo particular repugnancia’: The Office of Procurator through the Letters of Carlo Spinola S.J.,” Bulletin of Portuguese/Japanese Studies 20 (2010): 9–70.

[5] Elsa Penalva and Miguel Rodrigues Lourenço, eds., Fontes para a história de Macau no século XVII (Lisbon: Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau, 2009), 362.

[6] In total, I analyzed six regulations intended for Jesuit procurators: Fr. Alexandro Valignano, “Memorial de lo que ha de hazer el padre Alexandre Regio después de mi partida,” in Documenta Indica, ed. Joseph Wicki, S.J. (Rome: Monumenta Historica Societatis Iesu, 1966), 9:188–89; Valignano, “Regimento para el procurador de la India que reside em Portugal,” in Documenta Indica, ed. Joseph Wicki, S.J. (Rome: Monu- menta Historica Societatis Iesu, 1979), 14:748–60; Valignano, “Regras para o procurador do Japão,” in Do trato Português no Japão: Presenças que se cruzam (1543–1639), ed. Ana Prosérpio Leitão (Lisbon: Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, 1994), xxii–xlii; Francesco Pasio, “Regimento para o procurador do Japão que reside na China,” in Leitão, Do trato Português no Japão, xlii–xliii; “Regimento para o procurador da vice prouincia da China, que reside em Hamcheu,” 1622, fols. 309–10v, 49-V-7, Jesuítas na Ásia, Biblioteca da Ajuda; Fr João Rodrigues, “Couzas que podem servir para os procuradores,” 1629, Macao, fols. 635–48v, 49-V-8, Jesuítas na Ásia, Biblioteca da Ajuda.

[7] Rodrigues, “Couzas que podem servir para os procuradores,” 1629, Macao, fol. 645, Jesuítas na Ásia, Biblioteca da Ajuda.

[8] Felix Zubillaga, “El procurador de las Indias Occidentales de la Compañía de Jesús (1574): Etapas históricas de su erección,” Archivum historicum Societatis Iesu 22 (1953): 367–417.

[9] Augustin Galan-García, El “Ofício de Indias” de Sevilla y la organización económica y missional de la Compañía de Jesús (Seville: Fundacion fondo de cultura de Sevilla, 1996).

[10] Serafim Leite, História da Companhia de Jesus no Brasil, 10 vols. (Lisbon: Portugália, 1938–50).

[11] Dauril Alden, The Making of an Enterprise: The Society of Jesus in Portugal, Its Empire, and Beyond, 1540–1750 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996).

[12] João Paulo Oliveira e Costa, “O Cristianismo no Japão e o Episcopado de D. Luís de Cerqueira” (PhD diss., NOVA-FCSH, 1998).

[13] Mihoko Oka, “A Memorandum by Tçuzu Rodrigues: The Office of Procurador and Trade by the Jesuits in Japan,” Bulletin of Portuguese/Japanese Studies 13 (2006): 81–102; Frison, “‘El officio de procurador al qual aunque tengo particular repugnancia,’” 9–70.

[14] J. Gabriel Martínez-Serna, “Procurators and the Making of the Jesuits’ Atlantic Network,” in Soundings in Atlantic History: Latent Structures and Intellectual Currents, 1500–1830, ed. Bernard Bailyn and Patricia L. Denault (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 181–209.

[15] Charles J. Borges, The Economics of the Goa Jesuits, 1542–1759: An Explanation of Their Rise and Fall (New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, 1994); Borges, “The Portuguese Jesuits in Asia: Their Economic and Political Networking within Asia and with Europe,” in A Companhia de Jesus e a missionação no Oriente, ed. Nuno da Silva Gonçalves (Lisbon: Brotéria-Fundação Oriente, 2000), 203–24.

[16] Fred Vermote, “Finances of the Missions,” in A Companion to Early Modern Catholic Global Missions, ed. Ronnie Pochia Hsia (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 367–400; Vermote, “Financing Jesuit Missions,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Jesuits, ed. Ines G. Županov (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 128–52.

[17] Hélène Vu Thanh and Ines G. Županov, eds., Trade and Finance in Global Missions (16th–18th Centuries) (Leiden: Brill, 2020).

[18] Isabel Pina, “Businesses of China and Japan: The Procurators of the Jesuit Missões of East Asia,” in With Crucifies and Merchandisers by Distant Lands: The Society of Jesus and Its Economic Activities in the Iberian Empires, ed. Pedro Omar Wucherer (in press); Maria João Pereira Coutinho, “‘So many things I wanted from Guangzhou’: The Orders of two Jesuit Procurators; Francisco de Cordes (1688–1768) and José Rosado (1714–1797),” Orientis Aura: Macau Perspectives in Religious Studies 3 (2020): 103–22; Pereira Coutinho, “O papel dos procuradores-gerais da Companhia de Jesus no contexto das transferências artís- ticas do séc. XVIII,” paper presented at the Twenty-Third Congresso Nacional de Historia del Arte, 2021, 1273–84; Diogo Reis Pereira, “Entre Portugal e a China: Procuradores Jesuítas e seus negócios; O caso de António Freire (séc. XVII),” Daxiyangguo: Portuguese Journal of Asian Studies 29 (2022): 135–55; Leonor Prata, “Entre negócios e religião: O Irmão Jesuíta Manuel de Figueiredo (1589–1663),” Daxiyangguo: Portuguese Journal of Asian Studies 29 (2022): 113–34. These works were conducted under the guidance of Isabel Pina and Maria João Pereira Coutinho, who led the working group on procurators that came out of the Res Sinicae project, led by Arnaldo do Espírito Santo and Cristina Costa Gomes.

[19] Martínez-Serna, “Procurators and the Making of the Jesuits’ Atlantic Network,” 189.

[20] Alden, Making of an Enterprise, 17.

[21] Luke Clossey, Salvation and Globalization in the Early Jesuit Missions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 173.

[22] Clossey, Salvation and Globalization, 182.

[23] Martínez-Serna, “Procurators and the Making of the Jesuits’ Atlantic Network,” 181.

[24] Charles E. O’Neill and Joaquín María Dominguez, eds., Diccionario histórico de la Compañía de Jesús: Biográfico-temático (Madrid: Universidad Pontificia Comillas, 2001), 3244.

[25] Constituições da Companhia de Jesus e normas complementares (Lisbon: Provincial Curia of the Society of Jesus, 1997), 98, 147.

[26] This characterization of the Jesuit administration is used by Fabian Fechner, “Las tierras incógnitas de la administración jesuita: Toma de decisiones, gremios consultivos y evolución de normas” Historica 38 (2014): 11–42.

[27] Alden, Making of an Enterprise, 298–311.

[28] Pina, “Businesses of China and Japan.”

[29] Valignano, “Memorial de lo que ha de hazer el padre Alexandre Regio después de mi partida,” 188–89; Valignano, “Regimento para el procurador de la India que reside em Portugal,” 748–60.

[30] Pina, “Businesses of China and Japan.”

[31] Fr. Jorge de Gouveia, “Orçamento de contas da prouincia de Japão pera irem a Nosso Reverendo Padre Geral feito pello Padre Jorge de gouuea,” Lisbon, April 4, 1626, fols. 49–60v, Japonica Sinica 23, ARSI; Fr. António Freire, “Gastos que fez o Padre Antonio Freyre com os sugeitos da vice provincia da China anno de 1640,” Lisbon, 1640, fol. 514v, 49-V-11, Jesuítas na Ásia, Biblioteca da Ajuda.

[32] Valignano, “Regimento para el procurador de la India que reside em Portugal,” 748.

[33] Pina, “Businesses of China and Japan.”

[34] Letter from Fr. Manuel Borges to Superior General Muzio Vitelleschi, Macao, November 11, 1618, fol. 148, Japonica Sinica 34-I, ARSI.

[35] Alden, Making of an Enterprise, 304.

[36] Rodrigues, “Couzas que podem servir para os procuradores,” fol. 635.

[37] Alden, Making of an Enterprise, 308.

[38] Pina, “Businesses of China and Japan.”

[39] Fr. Manuel Barreto, “Memorial das couzas da procuratura desta provincia,” Macao, August 31, 1616, fols. 196–206v, 49-V-5, Jesuítas na Ásia, Biblioteca da Ajuda.

[40] Noël Golvers, Portuguese Books and Their Readers in the Jesuit Mission of China (17th–18th Centuries) (Lisbon: Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau, 2011).

[41] Barreto, “Memorial das couzas da procuratura desta provincia,” fols. 198v–199. The set of around 140 books present in Japan’s procuratura was first studied by Pierre Humbertclaude, “Investigações sobre um catalogo de livros pertencentes à Procura do Japão em Macau, em 1616,” Boletim eclesiastico da diocese de Macau 448 (1941): 147–61. More recently, Noël Golvers recovered his work and established a compara- tive analysis between the books present in the Macao procuratura in 1616 and those found there in later chronologies: Noël Golvers, “The Library Catalogue of Diogo Valente’s Book Collection in Macau (1633),” Bulletin of Portuguese-Japanese Studies 13 (2006): 7–43; Golvers, “‘Jesuit Macau’ and Its ‘Paper Collections’ in the Exchange of Knowledge between Europe and China (17th and 18th Centuries),” in Travels and Knowledge (China, Macau and Global Connections), ed. Luís Filipe Barreto and Wu Zhiliang (Lisbon: Centro Científico e Cultural de Macau, 2018), 179–202. Based on these studies, the information was systematized in my master’s thesis: “Jesuit Procurators in Macao: Networks of Contacts and Material Transfers in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century” (master’s thesis, NOVA-FCSH, 2024).

[42] Barreto, “Memorial das couzas da procuratura desta provincia,” fol. 205.

[43] Michael Cooper, Rodrigues the Interpreter: An Early Jesuit in Japan and China (New York: Weatherhill, 1974), 324.

[44] Pina, “Businesses of China and Japan.”

[45] Letter from Fr. Gabriel Matos to Superior General Muzio Vitelleschi, Macao, April 25, 1621, fols. 280– 82, Japonica Sinica 17, ARSI.

[46] Cooper, Rodrigues the Interpreter, 324.

[47] Letter from Fr. Gabriel Matos to Superior General Muzio Vitelleschi, fol. 281v.

[48] Gouveia, “Orçamento de contas da prouincia de Japão pera irem a Nosso Reverendo Padre Geral feito pello Padre Jorge de gouuea, Lisboa,” fols. 49–60v.

[49] Pereira Coutinho, “O papel dos procuradores-gerais,” 1277.

[50] I was able to identify the area of the store, in the old topography of the city of Lisbon, through: Ana Cristina Rijo, José Garcia, and Manuel Fialho Silva, “Uma vista desconhecida de Lisboa antes do Terramo- to: Problemáticas e possibilidades,” in A imagem de Lisboa: O Tejo e as leis Zenonianas da vista do mar, ed. Helder Carita and José Manuel Garcia (Lisbon: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa, 2019), 8–45.

[51] Rijo, Garcia, and Silva, “Uma vista desconhecida de Lisboa antes do Terramoto,” 30.

[52] Gouveia, “Orçamento de contas da prouincia de Japão pera irem a Nosso Reverendo Padre Geral feito pello Padre Jorge de gouuea,” fols. 51, 55v.

[53] Gouveia, “Orçamento de contas da prouincia de Japão pera irem a Nosso Reverendo Padre Geral feito pello Padre Jorge de gouuea,” 60.

[54] Gouveia, “Orçamento de contas da prouincia de Japão pera irem a Nosso Reverendo Padre Geral feito pello Padre Jorge de gouuea,” 59.

[55] “Decreto sobre as obras dos becos do Corpo Santo até aos Remolares,” Lisbon, December 7, 1669, fols. 107–107v, Livro 1º de consultas e decretos de D. Pedro II, Chancelaria Régia, Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa.

[56] See further Clossey, Salvation and Globalization in the Early Jesuit Missions.

[57] See further Paula Findlen, ed., Early Modern Thing: Objects and Their Histories, 1500–1800 (New York: Routledge, 2021), 2.

[58] See further Renata Ago et al., Gusto for Things: A History of Objects in Seventeenth-Century Rome (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013); Laurence Fontaine, Alternative Exchanges: Second-Hand Circulation from the Sixteenth Century to the Present (New York: Berghahn Books, 2008); Zoltán Biedermann, Anne Gerritsen, and Giorgio Riello, eds., Global Gifts: The Material Culture of Diplomacy in Early Modern Eurasia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

[59] Joseph Wicki, List of Jesuits: Indians, 1541–1758 (Münster, Aschendorff, 1967), 282–99.

[60] Alden, Making of an Enterprise, 298–318.

[61] Pina, “Businesses of China and Japan.”

[62] Cf. Noël Golvers, Francois De Rougemont, S.J., Missionary in Ch’Ang-Shu (Chiang-Nan): A Study of the Account Book (1674–1676) and the Elogium (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 1999).

[63] Penalva and Lourenço, Fontes para a história de Macau, 355.

[64] Letter from Fr. Manuel Borges to Superior General Muzio Vitelleschi, November 20, 1618, fol. 148, Japonica-Sinica, Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu.

[65] Cf. Gouveia, “Orçamento de contas da prouincia de Japão pera irem a Nosso Reverendo Padre Geral feito pello Padre Jorge de gouuea, Lisboa,” April 25, 1626, fols. 49–60v, Japonica Sinica 23, ARSI. António Freire, “Gastos que fez o Padre Antonio Freyre com os sugeitos da vice provincia da China anno de 1640,” fol. 514v.

[66] Fr. Manuel Borges, “Receita desta procuratura de japão em Macao,” Macao, August 8, 1618, fols. 127–40, 49-V-7, Jesuítas na Ásia, Biblioteca da Ajuda.

[67] Borges, “Receita desta procuratura de japan em Macao,” Macao, August 8, 1618, fol. 141, Jesuits in Asia, Ajuda Library.

[68] Borges, “Receita desta procuratura de japan em Macao,” fol. 141.

[69] Letter from Fr. António Freire, Lisbon, March 11, 1652, fols. 203v–205, 49-IV-61, Jesuítas na Ásia, Biblioteca da Ajuda.

[70] Fr. António Freire, “Gastos que fez o Padre António Freyre com os sugeitos da vice provincia da China anno 1640,” fols. 514–15v.

[71] Penalva and Lourenço, Fontes para a história de Macau no século XVII, 360–61.

- Title: Jesuit Procurators and the East Asian Missions in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century: – Material Cultures in Motion

- Author: Diogo Reis Pereira

Article Type: Research Article - DOI: 10.51238/ISJS.2023.11

Language: English - Pages: 1–18

- Keywords: Jesuit Procurators; East Asian Missions; Seventeenth Century; Jorge de Gouveia; António Freire

- Volume: 3

- Issue: 1, special issue

- Publication Date: 30 September 2025

Last Updated: 30 September 2025 - Publisher: Institute of Jesuit Sources

- E-ISSN: 2766-0644

- ISBN: 978-1-947617-35-3

APA

Reis Pereira, D. (2025). Jesuit procurators and the East Asian missions in the first half of the seventeenth century: Material cultures in motion. In A. Corsi, C. Ferlan, & F. Malta Romeiras (Eds.), Circa missiones: Jesuit understandings of mission through the centuries (Proceedings of the symposium held at Lisbon, Portugal, June 12–14, 2023) [Special issue]. International Symposia on Jesuit Studies, 3(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2023.11

CMOS

Reis Pereira, Diogo. “Jesuit Procurators and the East Asian Missions in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century: Material Cultures in Motion.” In “Circa Missiones: Jesuit Understandings of Mission through the Centuries (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Lisbon, Portugal, June 12–14, 2023),” ed. Alessandro Corsi, Claudio Ferlan and Francisco Malta Romeiras, special issue, International Symposia on Jesuit Studies 3, no. 1 (2025): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2023.11.

MLA

Reis Pereira, Diogo. “Jesuit Procurators and the East Asian Missions in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century: Material Cultures in Motion.” Circa Missiones: Jesuit Understandings of Mission through the Centuries (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Lisbon, Portugal, June 12–14, 2023), edited by Alessandro Corsi, Claudio Ferlan, and Francisco Malta Romeiras, special issue of International Symposia on Jesuit Studies, vol. 3, no. 1, 2025, pp. 1–18. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2023.11.

Turabian

Reis Pereira, Diogo. “Jesuit Procurators and the East Asian Missions in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century: Material Cultures in Motion.” In “Circa Missiones: Jesuit Understandings of Mission through the Centuries (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Lisbon, Portugal, June 12–14, 2023),” ed. Alessandro Corsi, Claudio Ferlan, and Francisco Malta Romeiras, special issue, International Symposia on Jesuit Studies 3, no. 1 (2025): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2023.11.

© Institute of Jesuit Sources, Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, All Rights Reserved