Research Article

The Jesuits and the Church in History

Part 2

Ambivalent Reception: Reflections on Jesuit Foundations by the Local Catholic Church in the Austrian Jesuit Province in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century

Kádár, Zsófia. “Ambivalent Reception: Reflections on Jesuit Foundations by the Local Catholic Church in the Austrian Jesuit Province in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century.” In “The Jesuits and the Church in History (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Boston, August 1–4, 2022),” ed. Claude Pavur, S.J., Barton Geger, S.J. and Robert Gerlich, S.J., special issue, International Symposia on Jesuit Studies 2, no. 1 (2023): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2022.11.

Introduction

On October 6, 1626, Gergely Nagyfalvy, canon of Győr, spent a sleepless night. On the previous evening, the Hungarian chancellor István Sennyei had arrived in the fortress town of Győr as a royal commissioner to organize the introduction of the Jesuits.[1] All this was the beginning of the years-long negotiation around settling the Society in the town, in which the local chapter did everything to prevent or delay the whole process. The case also illustrates how the local representatives of the secular church played a key role in the Jesuit foundations. There are numerous descriptions and analyses of the initial difficulties experienced by the Jesuits arriving in Protestant German towns and their conflicts with the local Protestants, specifically in the Habsburg monarchy, where the local societies were highly fragmented in terms of nationalities, denominations, and administrative affiliations.[2] In the last few decades, the “confessionalization theory” associated with Wolfgang Reinhard and Heinz Schilling has also drawn attention to interconfessional conflicts and relations. Despite several criticisms of this theory, several new studies have been carried out no longer focusing solely on the traditional Reformation–Counter-Reformation dichotomy but also analyzing the parallel phenomena of denomination building.[3] Yet we still have only a superficial understanding of the complex and often contradictory reactions within the Catholic community that were occasioned by the introduction of the Society.

This paper focuses on the local actors of the Catholic Church in the Jesuit foundation stories of the Austrian province. I examine the supporting or opposing attitudes of local bishops, middle and lower clergymen, and monks toward the Jesuits. We know the most about the middle clergy, primarily because the current literature examines the role of post-Tridentine bishops (including their relationship with the Society) in local case studies. Research on the lower clergy is more difficult and less advanced given the fragmentary historical sources. The local (collegiate) chapters are of particular interest, as they tend to be described as encumbrances to the reforms of Trent (1545–63), leading to a certain contrast being drawn between the Jesuits and an ecclesiastical group that was highly educated in (canon) law, occupied mostly with the administration of church estates, ecclesiastical jurisdiction, and diocesan administration (e.g., canonical visitations) rather than pastoral activity.[4]

There is undoubtedly a certain contrast between the canons, depicted as a coherent, “retrograde” group, and the “modern” Jesuits. This image arises from an analysis of a number of conflicts of interest: the rights and property of the chapter, pastoral authority, and the supervision of Catholic secondary education. At the local level, however, the support or rejection of the Jesuits cannot be simplified to such an extent.

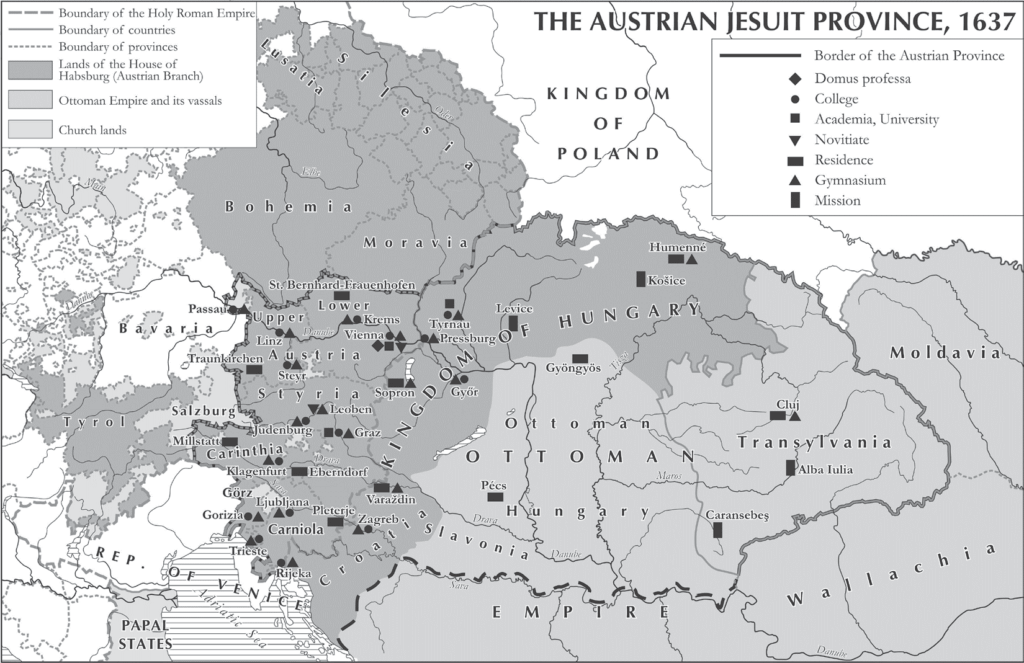

This is especially true in the former Austrian province (1563–1773), which, reflecting the interests of the Habsburg monarchs, included the Austrian hereditary provinces and the lands of the Hungarian crown.[5] (The lands of the Bohemian crown became an independent province in 1623.) The province’s extensive institutional expansion was also intertwined with the Counter-Reformation religious policy of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II (r.1619–37), which was supported on the Hungarian side by the Jesuit preacher (concionator) and later archbishop Péter Pázmány (archbishop of Esztergom, primate of Hungary, 1616–37). The actual power of the monarch and the political situation and the structures of the church were fundamentally different in Hungary, where, since 1608, the Jesuits were forbidden by law from owning properties.[6] In addition, in the Kingdom of Hungary—split into three parts after 1540 by the Ottoman conquest (the Habsburg territories, the Principality of Transylvania as an Ottoman vassal state, and the central “conquered” area under direct Ottoman control)—the Catholics were just one of the tolerated denominations; in large areas, Protestant doctrines spread unhindered in the towns, among the nobility, and even in small villages. Therefore, some of the dioceses functioned in title only.[7] The Austrian hereditary provinces, however, were mainly under the spiritual authority of two powerful dioceses: the archdiocese of Salzburg and the bishopric of Passau.[8] Both of these diocesan seats were outside the hereditary provinces and thus outside the direct influence of the Habsburgs. As the province of Lower Austria was, with the exception of Vienna, entirely part of the bishopric of Passau, the archdukes kept the bishops under pressure for their own interests, to counterbalance Bavarian influence.[9] The Habsburgs, besides their Counter-Reformation purposes and based on their archducal jurisdiction, also abolished and reorganized old monasteries and friaries.[10] The process was accompanied by fiery disputes, the so-called “monastery controversy,” but the whole situation enabled Ferdinand II to treat the Jesuits so generously that after his death he was remembered as the “founder of the [Austrian] Jesuit province.”[11] The flattering title does not seem to be an exaggeration if we look at the state of the province in 1637: the number of colleges had doubled as compared to 1608, while the total number of Jesuits exceeded their number before 1623, when the Bohemian province was separated from the Austrian one.

The present paper focuses on three examples from the central region of the Austrian Jesuit province, namely Krems, Pressburg (Pozsony, Bratislava), and Győr (Raab), from the 1610s to the 1620s. In the context of these three examples, almost parallel Jesuit foundations, I examine the reactions of the local actors of the Catholic Church: Who were they, and why did they support or oppose the arriving Jesuits?

The Austrian Jesuit Province, 1637. Concept: Zsófia Kádár, design: Béla Nagy

Krems

Krems was a merchant town in Lower Austria; together with its twin town of Stein, it enjoyed several municipal privileges and had a population of around three thousand at the end of the sixteenth century. Krems was also a seat of an archdeaconry in the diocese of Passau, and its archdeacon was often also the deputy of the bishop of Passau for secular affairs (“in temporalibus”), the so-called “officialis” in charge of Lower Austria. The re-Catholicization of the mixed Catholic–Lutheran population became intense in the 1580s under the officialis Melchior Khlesl (Klesl), a convert, who owed his own conversion to the Jesuits.[12] He invited Jesuit preachers to the town, among whom Georg Scherer was particularly influential.[13] The idea of founding a Jesuit college in Krems came up several times from the 1570s onward, but it was put on hold until a financially strong aristocratic patron was found in the person of Michael Adolf Graf von Althan, himself a convert.

Althan, a prominent field marshal of the Long Ottoman War (1593–1606), was raised to the rank of baron in 1608, at which time he came into closer contact with the aforementioned Khlesl.[14] By then, Khlesl was the bishop of Vienna and a trusted advisor to future emperor Matthias (r.1612–19), and he soon became chancellor, president of the Privy Council, and cardinal. It was he who initiated the foundation of the Jesuit college in Krems and called Althan’s attention to the town, where in 1615 the conditions were highly favorable for a stable Jesuit foundation.[15] Althan proved to be an extremely generous patron: in addition to the foundation grant of thirty-eight thousand florins, he gave a further thirty-two thousand florins for the purchase of several burgher houses. Through Khlesl’s intervention, the Jesuits were given the Church of the Virgin Mary with the associated beneficiary houses for the future Jesuit school. At the time, the church was under the jurisdiction of the Passau chapter and was then used by the town parish priest for communal purposes. However, the Passau chapter, which was located far away and received a minimal income from this church, imposed conditions on handing over the church and its appurtenances, fearing a violation of its own jurisdiction, which could set a dangerous precedent. The bishop of Passau, Leopold V of Habsburg, archduke of Austria, supported the transfer of the church in every way he could, so that the agreement with the hesitant canons did not take more than a few months. Bishop Khlesl even managed to minimize the conditions put forward by the mixed Catholic–Lutheran town council of Krems. In the end, the burghers were forced to agree to the loss of the Church of the Virgin Mary. Their only achievement in the negotiations was that they managed, though with great difficulty, to extort five thousand florins from Althan for the renovation of the town’s other, dilapidated church for parish purposes.[16]

If we look at the ecclesiastical actors involved in the foundation, it is clear this was an ideal situation for the Society of Jesus. The foundation was supported by the church leaders, the bishops of Passau and of Vienna. Indeed, their support was easy to acquire since their rights and possessions were not affected by the foundation.

Among the opponents were the representatives of the middle clergy. As mentioned, the jurisdiction of the Passau chapter was diminished by the foundation, to which the institution reacted sensitively but not too vehemently. Given the great distance from the seat of the chapter and the relatively small loss of material and prestige, the canons soon reached an agreement. Their terms reflected their legal view: they feared the alienation of their ecclesiastical property, were anxious about their rights to the beneficiary houses, and wanted to keep the income from the church’s endowed Masses for themselves. The bishop’s former officialis, Caspar Stredele, proved to be a weak hand in his office, remaining neutral toward the Jesuits. Only his successor, officialis Karl von Kirchberg, made repeated efforts to take steps against the Jesuits, fearing in particular their usurpation of parochial rights. Among the lower clergy, the parish priest of Krems, Zeno Ladiner, was the most involved, but he supported the Jesuits in all their endeavors.[17]

Members of other religious orders are only mentioned tangentially in the context of the Jesuit foundation, and they were largely supportive. The local Capuchins gave accommodation to the Jesuits for a short time. The Cistercian abbot of Göttweig, Georg Falb, had an intermediary role as a delegate of the bishop of Passau.[18] Though he was a monk, he acted on behalf of his prelate, and his previous good connections and Jesuit education also ensured his amicable relations with the Society.

Pressburg (Bratislava)

Pressburg (Pozsony, Bratislava)[19] was the most important secondary residence of the archbishops of Esztergom/primates of Hungary, and it was also the seat of a collegiate chapter. As the medieval capital of Hungary, Buda was under Ottoman control from 1541 onward, and Pressburg consequently became the seat of the Hungarian diets and several central (“state”) institutions. It was a free royal town, at that time inhabited partly by Protestant German burghers as well as many Slovak and Hungarian inhabitants, and the total population was above five thousand.[20]

The foundation of a Jesuit house was planned in Pressburg as early as the 1580s, and there was a mission station there from 1607 that was established in the time of Archbishop Ferenc Forgách.[21] A member of this mission was the young Jesuit Pázmány, the archbishop’s confessor, who later became the founder of the Jesuit college.[22] He started to promote the case of the college in 1617, when he himself was the archbishop. Since the local Lutheran Latin school was gaining greater influence and the collegiate chapter school was experiencing a period of crisis, the Jesuit foundation became urgent.[23] Eventually, in 1626, Pázmány himself made a foundation of fifty thousand florins for the establishment of the college.

As a free royal town, Pressburg stood under rather lax monarchial control. Therefore, when Emperor Ferdinand II informed the burghers about the introduction of the Jesuits and requested the transfer of the Catholic school building next to the parish and collegiate church of St. Martin to the Society, his command met significant local resistance, and Pázmány’s plans had to be modified. After several months of negotiations, the town council concluded a contract with the king, stipulating that the Jesuits could not expand within the territory of the town, that they could not infringe upon the urban patronage over the parish and other beneficiary houses, and that they could not sell their wine within the city’s walls. At the same time, Archbishop Pázmány was forced to negotiate with his own collegiate chapter, as he wanted to transfer two canonical houses to the Jesuits, which he promised to replace with other beneficiary houses. Due to the contract, the elementary school remained under the control of the chapter, which also retained all rights over the parish church under its jurisdiction. The Jesuits were only allowed to use the chapel of St Anne within the church and a total of three altars, and the members of the Society could only preach with the permission of the parish priest, who was always a canon of the chapter.

The buildings were taken over by György Forró, the rector of Trnava, on behalf of the Jesuits in the summer of 1627, and the school was opened in November. By 1635, a new college building had been constructed on the site of the former beneficiary houses, next to the parish church of St. Martin, for which Pázmány himself provided an additional 10,500 florins in cash. The canons of Pressburg, who were in daily contact with the local Jesuits through the common use of the church, were also involved in the supervision of the construction works. The chapter seems to have been sufficiently conscious of its own responsibilities, especially its legal and administrative functions, while leaving many pastoral tasks and the secondary education to the Jesuits.

A summary of the foundation reveals that in the case of Pressburg, the local arch- bishop himself was the founder, and despite its initial reservations and partly successful resistance, the local collegiate chapter soon found a modus vivendi with the new Jesuit college. The attitude of the other religious houses should also be mentioned. The local Poor Clare’s monastery also enjoyed the support of Archbishop Pázmány but initially had no meaningful relationship with the Jesuits.[24] By contrast, a kind of division of labor developed with the local Franciscans, since the Jesuits originally preached almost exclusively in German, while the Franciscans mainly used the Hungarian and Slovak languages. Finally, the very early community of the Congregation of Jesus, the religious sisters led by Mary Ward, should also be mentioned. They were invited by Pázmány to open a girls’ school in 1627/28 and cooperated closely with the local Jesuits during their short presence in Pressburg.[25]

Győr

The Hungarian town of Győr (contemporary German name: Raab) was one of the most important fortresses against the Ottomans, a fortified town with an essential military role: “The wall and shield of Vienna.” It was also an episcopal town, and thus a large part of it stood under the authority of the chapter as its landlord. Its inhabitants were largely Hungarian burghers, but many German soldiers also lived there. The fortress fell into Ottoman hands for four years (1594–98), but by the beginning of the seventeenth century civil society had reorganized itself; at that time, the town’s population was around three thousand.[26]

The foundation of the Jesuit college in Győr happened almost in parallel with that of Pressburg. At the initiative of Archbishop Pázmány, the diocesan bishop Miklós Dallos took up the Jesuit cause. Emperor Ferdinand II acted as the founder, since as monarch and the main ecclesiastical patron he could commission the estates of the former Cistercian nunnery of Veszprém for the maintenance of the new Jesuit college of Győr.[27]

Although the monarch became the official founder, the bishop was the key figure in the foundation. Bishop Dallos, from a local butcher family, was a member of a younger generation of bishops supported by Pázmány. Dallos first approached the imperial confessor, Wilhelm Lamormaini, in the summer of 1626, but the choice of the location for the future college was delayed for almost a year. The reason for this was that many buildings in the episcopal town-quarter, including the bishop’s palace itself, were used for military purposes: the donation of these houses was prevented by the local general, Hans Breuner. Thus, the bishop wanted to buy burgher houses for the Society in the larger part of the town owned by the chapter, that is, the “civic” part of the town, as opposed to the abovementioned, smaller episcopal town-quarter, to which proposal the canons agreed only after lengthy negotiations. The chapter, like the bishop, had already suffered many violations at the hands of the military and fought tooth and nail to defend its rights. A separate treaty was signed with the emperor and another with the incoming Jesuits. The chapter stipulated that the burghers’ houses handed over to the Jesuits would not be exempt from the landlord’s tax (census), and the Society was forbidden to acquire further property in the chapter’s quarter. The Jesuits were prohibited from alienating any benefices of the chapter or the cathedral. They could preach in Hungarian only with the bishop’s permission, but they were obliged to attend the processions and funerals of the canons with their prospective students. The chapter school and the small diocesan seminary were run by the chapter itself. The right of the chapter to keep a tavern could not be infringed by the college.

The self-defense of the chapter as a corporate entity against the Jesuits later continued despite some canons becoming benefactors of the Society. In the 1630s, the then bishop, György Draskovich, acquired new buildings for the Society on the market square, in addition to the burgher houses he had previously received, thereby violating the earlier agreement, a fact the chapter greatly resented. Still, the availability of a larger area, where no church buildings had stood before, enabled the construction of a large new church and then of a college and a gymnasium, which resulted in an almost uniquely favorable position within the town for the Jesuits in contemporary Hungary.[28] Their school, which opened in 1627, soon became very popular, and, as in Pressburg, they ministered to the town in a “division of labor” with the local Franciscans. In Győr, therefore, the loudest protest against the foundation came not from the organized opposition of the local Protestants (Lutheran German soldiers, Lutheran and Calvinist Hungarian burghers) but from the local clergy. Still, the chapter was not united on the question. The most scrupulous guardian of the chapter’s rights was the already mentioned custos, Gergely Nagyfalvy. Although he had studied under the Jesuits at the Collegium Germanicum-Hungaricum in Rome, and despite his excellence being acknowledged by the Jesuit György Káldy, who had preached in Győr for a few months in 1627, he always considered it illegitimate for the Society to acquire burgher houses in town. Nevertheless, the sympathy of other canons for the Jesuits soon prevailed: the provost of Pápóc, István Csiky Szentandrássi, accommodated the Jesuits in his own house for a while. The archdeacon of Sopron (Ödenburg), Farkas Wrachewich, also sided with them, and a decade after the foundation he bequeathed his own house in Győr to the local Jesuits.

As far as the monastic orders were concerned, only the Franciscans were present in the town at that time, with whom a division of labor was established: the German soldiers and the Hungarian burghers of the fortress town were similarly served by the members of both religious orders, but the linguistic divisions seen in Pressburg were not prevalent. The Franciscans and the Jesuits were equal partners in the pastoral service of the town, as demonstrated by the numerous members of the religious congregations led by the Franciscans and the Jesuits, and the many pious donations and testamentary legacies made to the orders and their churches.[29]

Conclusion

The three Jesuit foundation stories provide an insight into the Catholic confessionalization of a central region of the Habsburg monarchy, namely in Lower Austria and in the counties of Western Hungary. The towns and their regions under study brought with them a different legacy from the sixteenth century: although the Reformation was strong everywhere, especially in the towns, the dynamics of the Counter-Reformation and Catholic renewal were different. As this paper has shown, a well-organized re-Catholicization was already taking place in Lower Austria from the 1580s, under the control of the monarch, the Catholic ecclesiastical authorities (the Habsburg court, Khlesl as episcopal officialis), and a “state” institution, the Klosterrat, set up for this purpose.[30] The conditions for the Catholic renewal in Hungary were radically different, as the victory of Protestantism was complete in the kingdom by the end of the sixteenth century. Only the ruins of the Catholic institutional system remained, several bishoprics and entire chapters were vacant, and among the religious orders, apart from the Franciscans, only a few Pauline friaries and a couple of female houses remained; the monastic orders had been completely driven out of the kingdom.[31] The first great period of Catholic renewal (as already indicated) was marked by the name of Péter Pázmány, appointed archbishop of Esztergom as one of the four professed Jesuits, who contributed a great deal to the reorganization of the parish network, the support of religious orders, including the Jesuits, and the (re)conversion of the Hungarian elite to Catholicism.[32]

The Jesuits and diocesan priests in the case studies were thus living in a “transitional” period defined by the Protestant–Catholic conflict, but it was also an important initial period of Catholic renewal. It was therefore natural that the actors in the Catholic confessionalization—the bishops, the middle and lower clergy as well as the Jesuits— had to (re)position themselves within the church, find ways of cooperation, settle their conflicts, and, to this end, delimit their conflicting spheres of influence and activity. While the Catholic–Protestant antagonisms of the period are well documented in the historical sources and secondary literature (one only has to think of the religious disputes, the riots in the cities, and the civil wars),[33] the internal conflicts inside the Catholic Church are much more difficult to grasp and analyze. Some general conclusions can nevertheless be drawn from the examples presented, although many questions remain open.

As we have seen, the relations of the Jesuits with the members of monastic or mendicant orders left little mark in the records.[34] On the basis of our examples, we can speak about moderate support or neutrality, which could also involve a (linguistic) division of pastoral duties with the local Franciscans. In Hungary, this phenomenon, a language-based division of pastoral tasks between the Jesuits and other religious institutions (religious orders as well as local chapters or diocesan priests), persisted in several bilingual and trilingual towns during the seventeenth century and lost some of its importance only in the eighteenth century with the arrival of new or the return of old religious orders.

The prelates were fundamentally proactive and strong supporters of the Society. Yet their role was not exclusive: the Habsburgs, especially Emperor Ferdinand II, also played a key role in the analyzed period. The bishops, who were aware of the close connection between the Habsburg archdukes and the Jesuits, themselves became supporters of the Jesuit foundations. The only exception to this rule was the prince-archbishops of Salzburg, who, fearing the Society’s excessive influence, never allowed the Jesuits into their own territories.[35] Moreover, bishops in the Austrian territories rarely became real Jesuit founders: at the beginning of the seventeenth century, there were already financially powerful Catholic or convert aristocrats who could make foundations. In the Kingdom of Hungary, by contrast, this social group was still largely absent, so in many cases the prelates themselves made the foundations, or, through their efforts, the monarch nominally founded the college.

The role of the middle clergy was the most ambivalent. From the presented foundation cases, it became clear that on behalf of the chapters a recurring element was the fear of alienation of church property (urban buildings, churches, and landed estates) and their own medieval rights (e.g., income from taxes, duties or privileges for selling wine). This came on the top of the loss of prestige and material possessions already suffered due to the Reformation and the Ottoman wars. From the social recruitment of canons and members of the Society of Jesus, we can assume that they were partly (perhaps more often) from the same social strata, derived from the common nobles and the urban burghers. In terms of education, most of the future Jesuits were presumably educated at a Jesuit grammar school. For the future canons, Jesuit education (grammar school and university) only became a “matter of course” in the discussed region from the mid-seventeenth century, as the network of colleges and grammar schools in the Austrian Jesuit province entered a very dynamic, extensive phase from the 1610s to 1630s (during the reign of Emperor Ferdinand II). The first “masses” of students from the new Jesuit schools were admitted to the canons and religious (not only Jesuit) communities in the second half of the century. The different activity pro- files and career paths of the middle clergy and their Jesuit brothers, and the differences in the institutional systems behind them, perpetuated distrust and conflict between them even later, in an era when the education of prospective canons by Jesuit masters was already a widespread phenomenon. The analyzed cases show that respect for the rights of the chapters on the part of the college founders and the delimitation of their jurisdictions helped to overcome the initial opposition of the parties, which could then turn to collaboration, though in other places the grudge persisted.

The picture of the lower clergy’s role in Catholic confessionalization (on the basis of the relevant research) is a fragmented one.[36] The reforms of Trent had a profound impact on the education and conduct of parish priests, but the changes took effect only gradually. In the analyzed region, the lack of priests persisted during the early modern period. The disciplining role of bishops and diocesan synods progressed step by step, sometimes with resistance from the local Catholic communities. In the “remaining” Catholic villages of the vast rural areas outside the direct influence of the Catholic dioceses, in the Ottoman frontiers, the most important functions of the church (e.g., baptism, funeral, and elementary education) were performed in many places by secular auxiliaries (the so-called licentiatus). Even the Jesuit missionary reports show that the religious practice (praxis pietatis) was densely interwoven with “white magic,” superstitious beliefs, and even quackery. In this environment, the Jesuits were given the primary task not only of converting the Protestant inhabitants but also of caring for neglected Catholic communities. In the seventeenth century, it was mainly the occasional missions from the colleges and a few missions in the courts of aristocrats that provided them with this opportunity.

The first contact of local parish priests and chaplains with the Jesuits in the region may have begun at the grammar school, or perhaps from the 1580s, with the Jesuit missions. In Lower Austria, the aforementioned Khlesl, as episcopal officialis, not only called on Jesuit missionaries to convert Protestant villages but often also entrusted the correction of clerical morals to the Jesuits: he obliged parish priests living in concubinage to go to make confession or participate in spiritual exercises led by the Jesuits.[37] Local parish priests, as in the case of Krems, sometimes supported the incoming Jesuits, hoping for their help in pastoral work. In such cases, the basis for peaceful coexistence could again be the separation of jurisdictions.

Notes:

[1] This article was written with the support of Austrian Science Fund, “Lise Meitner”-Project no. M-3041. ORCID ID 0000-0002-4826-2179. Cf. László Szelestei N., ed., “Diarium Gregorii Nagyfalvi,” in Naplók és útleírások a 16–18. századból [Diaries and travel reports from the sixteenth–eighteenth centuries], Historia Litteraria 6 (Budapest: Universitas, 1998), 57–141, here 114–18.

[2] For an Austrian example with many Jesuit references, see Rudolf Leeb, Susanne Claudine Pils, and Thomas Winkelbauer, eds., Staatsmacht und Seelenheil: Gegenreformation und Geheimprotestantismus in der Habsburgermonarchie, Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 47 (Vienna: Böhlau, 2007).

[3] “Konfessionalisierungsthese”; on the theory and its critique, see Peter Hersche, Muße und Verschwen- dung: Europäische Gesellschaft und Kultur im Barockzeitalter, vols. 1–2 (Freiburg: Herder, 2006), 1:55–64.

[4] For a complex overview of the Catholic ecclesiastical class, including the middle clergy, mainly in the German context, see Hersche, Muße und Verschwendung, 247ff. (esp. 173, 259, 269–70, 277–80). Cf. also his relevant, earlier work: Peter Hersche, Die deutschen Domkapitel im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert (Bern: Juris Druck und Verlag, 1984). For a summary of recent Hungarian research, see Antal Molnár, “Katolikus egyházi középréteg a Magyar–Horvát Királyságban a 17. században” [The Catholic middle clergy in the Kingdom of Hungary and Croatia in the seventeenth century], in Katolikus egyházi társadalom a Magyar Királyságban a 17. században [Catholic ecclesiastical society in the Kingdom of Hungary in the seventeenth century], ed. Szabolcs Varga and Lázár Vértesi, Pécsi Egyháztörténeti Műhely 3 (Pécs: Történészcéh Egyesület and META-Egyesület, 2018), 67–91. In Hungary, as a specific feature, the participation of canons—primarily archdeacons—in pastoral activities occurred throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries due to a lack of parish priests.

[5] On the formation of the Austrian province, see László Lukács, ed., Catalogi personarum et officiorum provinciae Austriae S.I., vols. 1–2, Monumenta Historica Societatis Iesu 117, 125 (Rome: Institutum Historicum S.I., 1978, 1982), 1:1*–3*, 2:1*–3*.

[6] Péter Tusor, Pázmány, a jezsuita érsek: Kinevezésének története, 1615–1616 (Mikropolitikai tanulmány) [Pázmány, the Jesuit prelate: His appointment as primate of Hungary, 1615–16 (a micropolitical study)] Collectanea Vaticana Hungariae 1/13 (Budapest: Gondolat, 2016), 50–51; Zsófia Kádár, “Soprontól Pozso- nyig: A jezsuiták 17. századi országrendiségének kérdéséhez” [From Sopron to Pressburg (Bratislava): To the question of the Jesuit presence in the Hungarian diets in the seventeenth century], in Amikor Sopronra figyelt Európa: Az 1625. évi soproni koronázó országgyülés [When Europe’s attention was on Sopron: The coronation diet of Sopron in 1625], ed. Péter Dominkovits, Csaba Katona, and Géza Pálffy, Annales Archivi Soproniensis 2 (Sopron: MNL GyMSMSL, 2020), 473–543, esp. 476.

[7] For a recent summary of the contemporary history of Hungary, including the Reformation and the Catholic revival, see Géza Pálffy, Hungary between Two Empires 1526–1711, trans. David Robert Evans (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2021), esp. 91–99, 199–204.

[8] The two bishoprics founded in 1469, the bishopric of Vienna and the bishopric of Wiener Neustadt, had rather small territories, and their role in ecclesiastical politics was largely local. Erwin Glatz and Anton Landersdorfer, “Bistum und Hochstift Passau sowie Bistum Wien um 1500,” in Atlas zur Kirche in Geschichte und Gegenwart: Heiliges Römisches Reich—Deutschsprachige Länder, ed. Erwin Glatz et al. (Regensburg: Schnell und Steiner, 2009), 114–15.

[9] Thomas Winkelbauer, Ständefreiheit und Fürstenmacht: Länder und Untertanen des Hauses Habsburg im konfessionellen Zeitalter, vol. 2., Österreichische Geschichte 1522–1699 (Vienna: Ueberreuther, 2003), 55–63.

[10] On the relationship between Ferdinand II and the Jesuits, see Robert Bireley, Religion and Politics in the Age of the Counterreformation: Emperor Ferdinand II, William Lamormaini, S.J., and the Formation of Imperial Policy (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1981); on the “monastery controversy,” see 133–50.

[11] Elogia fundatorum et benefactorum collegiorum et domorum provinciae Austriae Societatis Iesu: Anno MDCLXXV (Archivum Provinciae Austriae Societatis Iesu, Vienna, Sign. 2 08 12 16), 29. “Ferdinandus se- cundus quem non modo huius collegii [Lincensis], sed totius pene provinciae nostrae fundatorem merito appellare possumus (vix enim est aliquod in ea domicilium, quod non ab ipso vel fundatum vel insigni beneficio auctum sit).”

[12] For the most recent biography of the officialis and Bishop Khlesl, see Michael Haberer, Kardinal Khlesl: Der Richelieu des Kaisers (Norderstedt: BoD, 2022).

[13] On the contemporary situation of Krems, the beginnings of the Counter-Reformation, and the role of officialis Melchior Khlesl, see Harry Kühnel, “Krems-Stein,” in Österreichischer Städteatlas, ed. Felix Czeike et al. (Vienna: Deuticke, 1977–2013), http://mapire.eu/oesterreichischer-staedteatlas/ (accessed September 18, 2023); Franz Schönfellner, Krems zwischen Reformation und Gegenreformation, Forschungen zur Landeskunde von Niederösterreich 24 (Vienna: Verein für Landeskunde von Niederösterreich, 1985), 285–89; Heidemarie Bachhofer, “Kaiser Matthias, Kardinal Khlesl und die Kremser Protestanten,” in Die Jesuiten in Krems—die Ankunft eines neuen Ordens in einer protestantischen Stadt im Jahr 1616, ed. Herbert Karner, Elisabeth Loinig, and Martin Scheutz, Studien und Forschungen aus dem Niederösterreichischen Institut für Landeskunde 71 (St. Pölten: Verlag NÖ Institut für Landeskunde, 2018), 27–52.

[14] On Michael Adolf Graf von Althan’s role as Jesuit founder, see Markus Jeitler, “Zur Person des Finanziers Michael Adolf von Althan (1574–1636): Kollegien in Krems, Iglau/Jihlava und Znaim/Znojmo,” in Karner, Loinig, and Scheutz, Die Jesuiten in Krems, 53–68; Antal Molnár, “Végvár és rekatolizáció: Althan Mihály Adolf és a magyarországi katolikus restauráció kezdetei” [Fortress and re-Catholicization: Michael Adolf Althan and the beginnings of the Catholic restoration in Hungary], in Idővel paloták […] Magyar udvari kultúra a 16–17. században [Over time, palaces (…) Hungarian court culture in the sixteenth to seventeenth centuries], ed. Nóra G. Etényi and Ildikó Horn (Budapest: Balassi, 2005), 390–98.

[15] For the details of the Jesuit foundation process in Krems, see Bernhard Duhr, Geschichte der Jesuiten in den Ländern deutscher Zunge, vol. 2/1, In den ersten Hälfte des XVII. Jahrhunderts (Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder, 1913), 322–25; Gerhard Rill, “Die Anfänge des Kremser Jesuitenkollegs,” Mitteilungen des Kremser Stadtarchivs 2 (1962): 73–96; Martin Scheutz, “Stadtrat versus Jesuiten: Kontrahenten um Stadtraum am Beispiel von Krems, Steyr und Leoben,” in Karner, Loinig, and Scheutz, Die Jesuiten in Krems, 69–110, esp. 79–85; Andrea Pühringer, “‘Topographie der Gegenreformation’ oder ‘Austrian Urban Renaissance’?,” in Leeb, Pils, and Winkelbauer, Staatsmacht und Seelenheil, 289–310, esp. 295–98.

[16] In addition to the rich historical sources cited in the literature, a remarkable summary of the foundation survived here: Elogia fundatorum et benefactorum, 41f.

[17] Cf. esp. Johannes Kritzl, “Krems 1616 versus Horn 1621: Zwei Jesuitengründungen und die Reaktion des Passauer Offizialats—ein Vergleich,” in Karner, Loinig, and Scheutz, Die Jesuiten in Krems, 114–19.

[18] Werner Telesko, “Die Göttweiger Äbte Georg Falb (reg. 1612–1631) und David Gregor Corner (reg. 1631–1648) in ihren Beziehungen zu den kremser Jesuiten,” in Karner, Loinig, and Scheutz, Die Jesuiten in Krems, 128–46.

[19] The early modern German name of the town was Pressburg; its Hungarian name was Pozsony. Today, it is the capital of Slovakia with the name of Bratislava. In the following, I will refer to the former trilingual (German, Hungarian, Slovak) town by its early modern German name, Pressburg.

[20] On the contemporary situation of the town and its church institutions, see István Fazekas, “A katolikus egyház helyzete és intézményrendszere a kora újkori Pozsonyban” [The position and institutional network of the Catholic Church in early modern Pressburg], Történelmi Szemle 60 (2018): 201–13; István H. Németh, “Pozsony centrális szerepköreinek hatásai és jellegzetességei a magyarországi városhálózatban” [The impacts and characteristics of Pressburg’s central roles within the Hungarian urban network], Történelmi Szemle 60 (2018): 171–99.

[21] On the foundation of the Jesuit college and its development in the seventeenth century, see Tamás Dénesi, “Missziótól a kollégiumig: Jezsuiták Pozsonyban 1635-ig” [From mission to college: The Jesuits in Pressburg until 1635], Magyar Egyháztörténeti Vázlatok, Regnum 10 (1998): 87–115; Zsófia Kádár, “A pozsonyi jezsuita kollégium mint összetett intézmény a 17. században” [The Jesuit college of Pressburg as a composite institution in the seventeenth century], Történelmi Szemle 60 (2018): 237–82; Kádár, Jezsuiták Nyugat-Magyarországon a 17. században: A pozsonyi, győri és soproni kollégiumok [ Jesuits in Western Hun- gary in the seventeenth century: The colleges of Pressburg, Győr, and Sopron], Monumenta Hungariae Historica: Dissertationes (Budapest: BTK Történettudományi Intézet, 2020), 43–54, 65–69, 83–90.

[22] Important Jesuit sources on the foundation and the founder: Historia collegii Posoniensis Anno Domini 1622 [1622–35]. University Library of Eötvös Loránd University (Budapest), Manuscript Collection, Ab 97. and Elogia fundatorum et benefactorum, 54–56.

[23] The crisis of the humanist chapter school was linked to the fact that the town was dominated by Protestant (German-speaking) burghers, who, in addition to their elementary school, also established a high-quality secondary school during this period. In this competitive situation, the chapter school seemed to be falling behind. Thus, in Pressburg the prestigious Lutheran lyceum had no viable Catholic alternative before 1626.

[24] The new cloister of the Poor Clare’s was built in Pressburg at the same time as the Jesuit college and was also financed by Archbishop Pázmány. Ivan Rusina et al., Barok: Dejiny slovenského výtvarného umenia [Baroque: History of Slovak fine arts] (Bratislava: Slovenská národná galéria, 1998), 386 (no. 3).

[25] Josef Grisar, Maria Wards Institut vor römischen Kongregationen (1616–1630) (Rome: Pontificia Università Gregoriana, 1966), 298–304, cf. Kádár, Jezsuiták Nyugat-Magyarországon, 49–53.

[26] On the contemporary history of the fortress town of Győr, see Géza Pálffy, A császárváros védelmében: A győri főkapitányság története 1526–1598 [In defense of the imperial city of Vienna: The border fortress-cap- tain-generalcy of Győr 1526–98] (Győr: GyMSMGyL, 1999), esp. 208–27; Lajos Gecsényi, Gazdaság, tár- sadalom, igazgatás: Tanulmányok a kora újkor történetéből [Economy, society, administration: Studies on early modern history] (Győr: GyMSMGyL–GyMJVL, 2008); István Fazekas, “Győr és a jezsuita rend a 17. században: Szereplők, érdekek, ellenérdekek” [Győr and the Society of Jesus in the seventeenth century: Actors, interests, counter-interests], in Jezsuita jelenlét Győrben a 17–18. században: Tanulmányok a 375 éves Szent Ignác-templom történetéhez [ Jesuit presence in Győr in the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries: Studies on the history of the 375-year-old Saint Ignatius Church], ed. István Fazekas, Zsófia Kádár, and Zsolt Kökényesi (Győr: Szent Mór Bencés Perjelség, 2017), 63–85.

[27] On the foundation of the Jesuit college and its development in the seventeenth century, see Ferenc Acsay, A győri kath. főgimnázium története 1626–1900 [History of the Catholic grammar school of Győr 1626–1900] (Győr: Győri Egyházmegye, 1901), 9–38; Zsófia Kádár, “A győri jezsuita kollégium intézményi funkciói a 17. században, 1626–1671” [The institutional functions of the Jesuit college in Győr in the seventeenth century, 1626–71], in Fazekas, Kádár, and Kökényesi, Jezsuita jelenlét Győrben, 87–131; Kádár, Jezsuiták Nyugat-Magyarországon, 54–59, 70–75, 90–105. The historical sources of the Jesuit foundation of Győr are scattered, and no historia domus or diary is known. My primary sources: Litterae annuae [Provinciae Austriae], Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu, Rome, Austr. 135, 136 (passim) and the documents of the Diocesan Archives of Győr (Győri Egyházmegyei Levéltár), Archives of the Chapter, Private Archive, Cimeliotheca XII and Archive of the “place of authentication” (locus credibilis), Theca XXVII.

[28] István Fazekas and Zsófia Kádár, “A győri jezsuita templom 17. századi jótevői: A támogatók körének rekonstrukciója” [The seventeenth century benefactors of the Jesuit church of Győr: Reconstruction of the circle of patrons], in Fazekas, Kádár, and Kökényesi, Jezsuita jelenlét Győrben, 13–58.

[29] Kádár, Jezsuiták Nyugat-Magyarországon, 56–57; József Horváth, “Végrendeleti adományok a győri jezsuiták és más egyházi testületek javára a 17. században” [Testamentary donations to the Jesuits of Győr and other ecclesiastical institutions in the seventeenth century], in Fazekas, Kádár, and Kökényesi, Jezsuita jelenlét Győrben, 273–305.

[30] Winkelbauer, Ständefreiheit und Fürstenmacht, 113–16.

[31] On the territories occupied by the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans and the Kingdom of Hungary, and their Catholic confessionalization, see most recently Antal Molnár, Confessionalizastion on the Frontier: The Balkan Catholics between Roman Reform and Ottoman Reality, Interadria, Culture dell’Adriatico 22 (Rome: Viella, 2019), esp. 41–44.

[32] For a still crucial analysis of Pázmány’s oeuvre, see Vilmos Fraknói [Frankl], Pázmány Péter és kora [Péter Pázmány and his age], vol. 1, (1570–1621), vol. 2, (1622–1631), vol. 3, (1632–1637) (Pest: Ráth Mór, 1868, 1869, 1872), cf. the recent historiography on the archbishop, e.g., Tusor, Pázmány, a jezsuita érsek.

[33] For a few selected examples from the analyzed region, with Jesuit aspects, see Martin Scheutz, “Kammergut und/oder eigener Stand? Landesfürstliche Städte und Märkte und der ‘Zugriff’ der Gegenreformation,” in Leeb, Pils, and Winkelbauer, Staatsmacht und Seelenheil, 311–39; Katalin Péter, Studies on the History of the Reformation in Hungary and Transylvania, ed. Gabriella Erdélyi, Refo500 Academic Studies 45 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2018); Antal Molnár, Mezőváros és katolicizmus: Katolikus egyház az egri püspökség hódoltsági területein a 17. században [Market town and Catholicism: Catholic Church in the conquered territories of the bishopric of Eger in the seventeenth century], METEM könyvek 49 (Budapest: METEM, 2005); Béla Mihalik, “Sacred Urban Spaces in Seventeenth-Century Upper Hungary,” Hungarian Historical Review 1, nos. 1–2 (2012): 22–48, https://hunghist.org/images/volumes/Volume_1_Issue_1-2/ Mihalik.pdf (accessed September 18, 2023); Paul Shore, Narratives of Adversity: Jesuits in the Eastern Peripheries of the Habsburg Realms (1640–1773) (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2011), cf. with a critique of this interpretation: Barbara Hodásová, “Narratives of Adversity or Microhistories of Sources? The Case of Jesuits in Banská Bystrica,” Umeni 67, no. 3 (2019): 184–214.

[34] Primarily concerning the Jesuit foundations, later connections can be better identified, cf. e.g., Helga Penz, “‘Jesuitisieren der alten Orden’? Anmerkungen zum Verhältnis der Gesellschaft Jesu zu den österreichischen Stiften im konfessionellen Zeitalter,” in Jesuitische Frömmigkeitskulturen: Konfessionelle Interaktion in Ostmitteleuropa 1570–1700, ed. Anna Ohlidal and Stefan Samerski, Forschungen zur Geschichte und Kultur des östlichen Mitteleuropa 28 (Stuttgart: Steiner, 2006), 143–61.

[35] Winkelbauer, Ständefreiheit und Fürstenmacht, 30–35.

[36] See Hersche, Muße und Verschwendung, esp. 259–61, 283–88, 290–95, and relevant Hungarian re- search: István Fazekas, “A győri egyházmegye katolikus alsópapsága 1641–1714 között” [The Catholic lower clergy of the Győr diocese in 1641–1714], in István Fazekas, A reformútján: A katolikus megújulás Nyugat-Magyarországon [On the path of reform: The Catholic renewal in Western Hungary], A Győri Egyházmegyei Levéltár Kiadványai: Források, feldolgozások 20 (Győr: Győri Egyházmegyei Levéltár, 2014), 69–129; Dániel Bárth, “The Lower Clergy and Popular Culture: Introductory Remarks to a Current Research Project,” Historical Studies on Central Europe 1, no. 1 (2021): 177–212, https://ojs.elte.hu/hsce/article/view/898/2166 (accessed September 18, 2023).

[37] Kritzl, “Krems 1616,” 115.

- Title: Ambivalent Reception: Reflections on Jesuit Foundations by the Local Catholic Church in the Austrian Jesuit Province in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century

Author: Zsófia Kádár

Article Type: Research Article

DOI: 10.51238/ISJS.2022.11

Language: English

Pages: 1–13

Keywords: - Volume: 2

- Issue: 1, special issue

- In: The Jesuits and the Church in History

- Editors: Claude Pavur, S.J., Barton Geger, S.J., and Robert Gerlich, S.J.

- In: International Symposia on Jesuit Studies

Publication Date: 30 November 2023

Last Updated: 30 November 2023

Publisher: Institute of Jesuit Sources

E-ISSN: 2766-0644

ISBN: 978-1-947617-19-3

APA

Kádár, Z. (2023). Ambivalent reception: Reflections on Jesuit foundations by the local Catholic Church in the Austrian Jesuit Province in the first half of the seventeenth century. In C. Pavur, S.J., B. Geger, S.J., & R. Gerlich, S.J. (Eds.), The Jesuits and the Church in history (Proceedings of the symposium held at Boston, August 1–4, 2022) [Special issue]. International Symposia on Jesuit Studies, 2(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2022.11

CMOS

Kádár, Zsófia. “Ambivalent Reception: Reflections on Jesuit Foundations by the Local Catholic Church in the Austrian Jesuit Province in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century.” In “The Jesuits and the Church in History (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Boston, August 1–4, 2022),” ed. Claude Pavur, S.J., Barton Geger, S.J. and Robert Gerlich, S.J., special issue, International Symposia on Jesuit Studies 2, no. 1 (2023): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2022.11.

MLA

Kádár, Zsófia. “Ambivalent Reception: Reflections on Jesuit Foundations by the Local Catholic Church in the Austrian Jesuit Province in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century.” The Jesuits and the Church in History (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Boston, August 1–4, 2022), edited by Claude Pavur, S.J., Barton Geger, S.J., and Robert Gerlich, S.J., special issue of International Symposia on Jesuit Studies, vol. 2, no. 1, 2023, pp. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2022.11.

Turabian

Kádár, Zsófia. “Ambivalent Reception: Reflections on Jesuit Foundations by the Local Catholic Church in the Austrian Jesuit Province in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century.” In “The Jesuits and the Church in History (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Boston, August 1–4, 2022),” ed. Claude Pavur, S.J., Barton Geger, S.J., and Robert Gerlich, S.J., special issue, International Symposia on Jesuit Studies 2, no. 1 (2023): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2022.11.

© Institute of Jesuit Sources, Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, All Rights Reserved