Research Article

The Jesuits and the Church in History

Part 2

Martyrdom in the Library: The Books of the Early Modern Jesuit Novitiate in Mainz (Germany)

Frei, Elisa. “Martyrdom in the Library: The Books of the Early Modern Jesuit Novitiate in Mainz (Germany).” In “The Jesuits and the Church in History (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Boston, August 1–4, 2022),” ed. Claude Pavur, S.J., Barton Geger, S.J. and Robert Gerlich, S.J., special issue, International Symposia on Jesuit Studies 2, no. 1 (2023): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2022.08.

Introduction

This paper presents the results of an ongoing research project that identifies how many and which missionary books—especially regarding the East Indies and focusing on martyrs—were available to the young Jesuits living in Mainz in the early modern period. Through analysis of the material pertaining to the collection of books previously held by the local novitiate, this essay sheds some important light on a historiographical question of global significance: What were the literary sources of the Jesuit vocations to the overseas missions?

Located in central-western Germany, Mainz is the capital and largest city of Rhine- land-Palatinate. Politically, in the early modern period Mainz was part of the German empire; from a Jesuit perspective, it was part of the province Rhenania Superior, a sub- division of the German assistancy. Starting in the 1580s, the Jesuits of Mainz were part of an important religious community of Central Europe.[1] Even more than members of other Catholic orders, however, the members of the Society of Jesus were supposed to be ready to move to every part of the world as missionaries.

The title of the project, supported by a ReIReS short fellowship, is “The Literary Sources of the Jesuit Vocation for the East Asian Missions (Mainz, 17th–18th Centuries).”[2] It identifies which books on the East Indies were available to the young Jesuits living in Mainz and explores how this material may have influenced their vocation to the overseas missions. The Jesuit books on which this paper focuses are currently preserved in the Wissenschaftliche Stadtbibliothek (and partially in the Martinus Bibliothek)[3] together with many other items belonging to the Society of Jesus in the early modern period.

The project seeks to answer several research questions: How did the fourth vow— obedience to the pope circa missiones—influence the Jesuit collections? Did Jesuit houses solely preserve the missionary books printed by their order and nothing more? Was there any overlap between Jesuit missionary bibliography and the books that were actually available in Jesuit libraries? How did the acquisition and selection policies of books on missionary topics operate? Were non-Catholic books on geographic discoveries ever used in Jesuit libraries?

This project is closely connected to wider research on the Litterae indipetae.[4] From the sixteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries, Jesuits wrote directly to superiors general of the Society of Jesus to request missionary assignments abroad. These petitions have become known as the Indipetae, a term derived from the Latin Indias petens, meaning “asking for the Indies.” The term “Indies” was understood to include both Asia and the Americas, but the present research has mainly focused on the East Indies. The Roman archives of the Society of Jesus hold over twenty-two thousand Indipetae letters written by European Jesuits before the Society’s suppression (1773) and after its full restoration (1814).

The question of the missionary vocation of the Jesuits is strongly rooted in and distinctive of the order. However, research shows that the Indipetae are not the right place to explore the literary sources of this institutional character. Jesuits were usually extremely reserved in their applications; very rarely did they mention any details about the books they had been reading. The most cited authors are Francis Xavier (1506–52) and his epistolary; the works of the founder himself, Ignatius of Loyola (c.1491–1556); and Daniello Bartoli (1608–85) and his histories of the first century of the Society of Jesus.

Another way to reconstruct the Jesuits’ literary horizon, therefore, consists in concretely analyzing which texts were available in their residences. As for the German assistancy, following the “great secularization” of 1803—when people and properties managed and owned by the ecclesiastical authorities were transferred to the secular domain—many of the Society’s rare manuscripts and printed materials were scattered in different cultural institutions.[5] This material became the basis of a significant case- study, aimed at tracing the origins of the expectations and dreams of young European Jesuits about missions, especially in East Asia. It was precisely during their novitiate, in fact, that most Jesuits started sending their petitions for the Indies, and it was during those same years, fundamental for their formation and vocation, that some of them became insistent and committed petitioners. The duration of their Indias petens phase could vary considerably, from a one-time petition to unsuccessful applications submitted repeatedly over decades. Although this research started bibliocentrically, the aim is to answer broader historiographical questions—and further research will make that possible.

It could naively be objected—as the historian Edward Gibbon (1737–94) did in the mid-eighteenth century—that every Jesuit house merely preserved the missionary books printed by the Society of Jesus, and nothing more.[6] However, this would be a simplification. Verifying the presence of library material in the Jesuit novitiate of Mainz can also help us to understand the acquisition and selection policies of books on missionary topics and to ascertain how often the Jesuit bibliography did not correspond to the actual patrimony of a given Jesuit residence. This research can be put into dialogue with other studies on the early modern library to verify similarities and differences in the collection and preservation of the material.

The research in the libraries of Mainz confirmed that, among the Jesuit novitiate’s books on missions, martyrdom, and travels, there was much material not written, printed, or commissioned by the Society of Jesus. Mainz was a city of the German empire with a relevant Catholic presence; the German Jesuits, however, had very little hope of being sent as missionaries because such assignments were much more prob- able for members of the Iberian realms (Spain and Portugal) or Italy (which was partly under their dominion). The German empire did not have overseas territories, and, moreover, the Jesuits played an extremely important role in Germany because they had to fight an equally important “mission”: the one against the Protestants. Nonetheless, the circulation of Jesuit missionary works throughout Europe worked very well, and the library of the Jesuit novitiate of Mainz had many and updated books on Asian missions in particular and geographical discoveries in general.[7]

Libraries in the Society of Jesus

From the first decades after the foundation of the Society of Jesus, the order’s members were aware of the importance of books—and consequently also of their acquisition, circulation, and preservation.[8] Peter Canisius (1521–97), one of the first Jesuits and one of the first to establish missions in German territories, claimed that he preferred “a college without a proper church above a college without a library.”[9] From the 1550s until the suppression of the order (1773), Jesuits amassed book collections that exceed- ed five million items in the German territories alone.[10] A “highly significant library landscape” was thus an integral part of their “worldwide missionary, pastoral, cultural and educational activities.”[11] Jesuit libraries were “the weight-bearing structure of the whole curriculum of teachers and students,”[12] and they were often on a par with the most documented and up to date cultural institutions of the early modern period. In- deed, according to Noël Golvers, “Jesuit libraries and librarianships, in Europe and in the missions, can be considered as the basis of modern librarianship and libraries.”[13]

In Europe, books played a vital role in the Jesuits’ teaching activities, preaching, and work in the local missions—but they were also of the utmost importance overseas.[14] Especially when operating in ancient and educated civilizations like the Ming and Qing empires, books were necessary as “repositories of Western spirituality, experience, and knowledge,” as mines of material to fight back against religious adversaries, and finally, “through their ‘exotic’ aspects and the particular ornatus of the individual books,” they could have “an immediate, positive impact on the position of the missionaries.”[15] Books were thus important not only for their content but for their form as well.

The Society’s leaders understood how important it was to establish a uniform policy regarding books.[16] The first draft of the Ratio studiorum (1586) claimed that Jesuits were like soldiers and that they could not fight without weapons: they needed a proper arsenal for their religious and intellectual battle—books.[17] The Ratio studiorum stipulated that every Jesuit institution must have a library and that a set amount of money should be regularly allocated to managing and increasing their collections. Other rules are dedicated to libraries as well,[18] prescribing how a praefectus bibliothecae (head librarian) had to be appointed to manage them, deciding who could borrow books, and how collections had to be updated based on the interests of its users. Even more important was the role of the bibliothecarius (librarian) in Jesuit university libraries; additional regulations dated several decades later (1658) show a new awareness of his responsibilities—and probably an increased experience in librarianship.[19] These updated rules underline the importance of keeping track of the users of the library: if they did not give the books back, new ones should not be loaned to them. The collection had to be updated so that it incorporated the latest publications sold at the most recent book fairs,[20] everything had to be meticulously registered, and the library should only be accessed under the librarian’s eyes—and key.

Further rules, available in the definitive edition of the Ratio studiorum (1599),[21]

established that praefecti bibliothecae (librarian prefects) should preserve the book collections, know which books they contain, display the books publicly (for the students of the college, but not exclusively), and take care of the needs of the users (not buying and keeping books nobody uses and tailoring the collections to readers’ needs).

The guidelines for libraries and librarians stipulated that Jesuit acquisitions could not include books condemned in the Index librorum prohibitorum. This included Latin and Greek authors, or part of their books if the content was not morally appropriate,[22] but the ban also covered more recent works containing sentences the Inquisition want- ed to erase. On the other hand, there were some lists containing recommended titles for purchase and preservation. The most famous are Antonio Possevino’s Bibliotheca selecta de ratione studiorum (Library selected for the purpose of study [1st ed. Rome, 1593; 1st German ed. Cologne, 1607]) and Apparatus sacer ad scriptores Veteris et Novi Testamenti (Sacred apparatus to the authors of the Old and New Testaments [Venice, 1603–9]),[23] which list hundreds of titles and authors that were considered appropriate readings for Jesuits, dividing the materials into seven categories. The head librarian and the master of novices were responsible for these acquisitions and for deciding who was allowed to borrow the material.[24] Another example is Claude Clément’s Musei sive bibliothecae tam privatae quam publicae extructio, instruction, cura, usus libri IV (Four books about the building, arrangement, and care of museums or libraries, both private and public [Lyon: Jac. Prost, 1635]).

The Jesuit Libraries in Mainz

The Jesuits arrived in Mainz in 1561, with the founding of their first college in the city.[25] The local religious authorities had already amassed a corpus of books, so the Jesuit library at the college did not start from nothing. Moreover, the elector princes of the city were archbishops, always worried to be able to properly fight back against the Protestant advance. Jesuits could play a key role in the Catholic cause, and their presence was always welcomed and supported.

Yet, notwithstanding this broadly favorable context, Jesuit activities and structures were put at risk many times because of the periodic wars affecting Germany, in particular the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48). Even if Mainz was involved in the conflict, the Jesuit library and college were never destroyed. There was some luck in this, because when King Gustav Adolf of Sweden (r.1611–32) conquered the city in 1631, he closed the college and confiscated the library. Some of the most precious Jesuit books from Mainz are therefore still preserved in the Uppsala University library,[26] but most were bought back and returned to Germany by 1636—the year in which the Jesuits got their college back as well.

After the Thirty Years’ War, the Jesuit library of Mainz was rebuilt and ordered again, as the catalogs show. As often happens, the very first catalogs are no longer available. The oldest preserved catalog, the Catalogus universalis I,[27] is dated June 1674 and alphabetically lists the titles of the books written by Jesuits and non-Jesuit authors. The catalog contains the name and surname of the author (Nomen et cognomen scriptoris), title of the book (Titulus libri), the book’s format (Quantitas libri), its location (Armarium and Series), and finally how many copies there were (Numerus exemplarium).[28]

Another Catalogus universalis (II) lists the family names and names of the authors of the above-mentioned books. Completed in July of the same year (1674), it allowed library visitors to find the books written by a certain author without knowing the booktitles. A third catalog, the Catalogus universalis III, lists research by keywords and could be used by Jesuits who were studying a certain subject but did not know who had written about it—subjects like Mogor (the Mughal empire), Moguntia (Mainz), and so on.[29] Thanks to these catalogs, we know that in 1674 the library of the Jesuit college of Mainz contained as many as 13,800 books (even if some of them were duplicates).

The Jesuits in Mainz had a library for the college and another library for the novitiate, which was founded in 1648 as part of the Oberrheinische Provinz. The Jesuit novitiate itself was an impressive building: together with the Jesuit church, chapel, and college, it occupied a larger percentage of the city than the structures belonging to other religious orders such as the Franciscans,[30] thus reflecting the Society’s importance in Mainz. The novitiate was always home to around fifty to sixty young Jesuits.[31] The library of the Jesuit novitiate was on the second floor of the building, over the Josephskapelle. A catalog dated 1743 lists the books and attests that the novitiate’s library collection stood at about 3,200 volumes.[32]

In 1773, the Society of Jesus was officially suppressed by the papal brief Dominus ac Redemptor, and all the Jesuit structures in Mainz were transferred to the city’s authorities. Among the most concrete traces Jesuits left were their libraries, as their books were prized by many.[33] Jesuits had played a vital role in education and science in the city from the second half of the sixteenth until the end of the eighteenth century. Most of the city’s jurists, philosophers, historians, and scientists studied in their schools. While the college of Mainz was closed, the books consequently remained in the same building for some time. In 1784, the University of Mainz was reorganized and took possession of the books. In 1805, the library of the university became the city library (Stadtbibliothek), which is the present location of the majority of the Jesuit collection. The books were an important resource, especially for those studying pedagogy, philosophy, theology, history, philology, and law.

The Literary Sources of the Jesuit Vocation for the East Asian Missions (Mainz, Seventeenth to Eighteenth Centuries)

This investigation began with the online catalog of the Wissenschaftliche Stadtbibliothek, which allows research based on the provenience of the funds and lists about one thousand books from the Oberrheinische Provinz. Analyzing these entries, the present research has focused on the material that could help answer the questions mentioned above: What were the literary sources of the missionary vocations of the novitiate in Mainz? Which books were available to those studying to become Jesuits in a Central European institution of the early modern period?

Jesuit libraries were characterized by “structural uniformity and […] manifold functions […], being instruments of ‘public relations’ to centers of study, translation, and production, as ‘open’ collections interwoven with the regional context.”[34] As for the subjects, it is clear that theology held first place.[35] Theological works constituted almost half of the Jesuit library: Bibles, translations, Vulgata, illustrated versions, patristic literature (Augustine, John Chrysostom), preaching material. Jesuits were the authors best represented, but there was a large number of non-Jesuit writers as well. The second main topic was history, which constituted between fifteen and twenty percent of the collections. Many of the historical books were about the territories where the Jesuits had established their missions—which are the main focus of the present research. Historical subjects could be intertwined with geographical ones: travelogues, accounts, and memoirs often collected information both on the history of a place and on how to reach it and travel through it. More strictly geographical books included atlases, maps, and itineraria (travel guides for certain cities and territories). Around fifteen percent of the books were literature, including, of course, all the classics, those being essential for teaching in Jesuit schools, but more recent publications were also present. A small quota of books were about law, philosophy, and the sciences: natural science, medicine, mathematics, geometry, astronomy, physics, and so on. Finally, as in every library, some books—around ten per cent in this case—could only be classified as Miscellanea.

There are about one thousand books in the Wissenschaftliche Stadtbibliothek that were once owned by the novitiate’s library in Mainz. This article presents the partial results of an ongoing research project focused on the titles concerning missions, martyrdom, and travels, numbering about one hundred. For each book, the main data were collected for an online database[36] and pictures were taken of the cover, the frontispiece, drawings, and handwritten notes testifying to the passage of the books from one owner to another during the centuries.

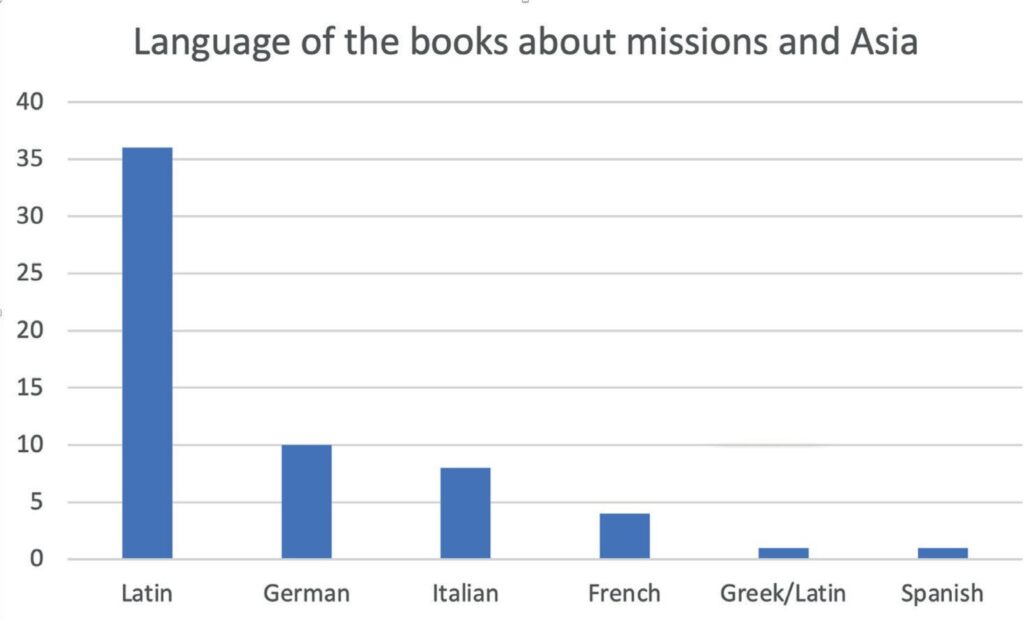

Most of the books, predictably, were written in Latin (sixty percent). The second group was written in German (seventeen percent), not very far from those written in Italian (thirteen percent). Several books were in French (seven percent), a few in Spanish and Greek/Latin (two percent each), but there are no traces of Portuguese books concerning the East Asian missions. This last finding is a further indication that few Germans left for the overseas missions, given that most of them were under the control of the Portuguese Padroado, which would have required traveling on Portuguese ships, and a considerable number of books focused on Portugal’s discoveries in East Asia were published in Portuguese.

Another question is how thoroughly the books were read—or even if they were read at all. One indication of usage is the number of annotations: some books seemed completely untouched, whereas others contained very interesting markings. This analysis focused on three kinds of notes that are not peculiar to the Society of Jesus but can be seen in materials from any library of the time.

The first type of annotation consists of censures made by chaste readers, who used to put pants on depictions of naked angels or women.[37] You see above the frontispiece of one of the many atlases by Gerard Mercator (1512–94) (Atlas sive Cosmographicae meditationes de fabrica mundi et fabricati figura [Atlas or cosmographical meditations: On the creation and form of the world (Amsterdam, 1613)]). All the continents are represented by naked women, but only the last one was covered. Similarly, in Gabriel Bodenehr’s (1673–1765) Atlas Curieux oder Neuer und Compendieuser Atlas in welchem ausser den General Land Charten von America, Africa, Asia und Europa, und der in letzteren Kriegen renommiert worden, enthalten sind (Curious atlas, or new and summarized atlas, which contains the general maps of America, Africa, Asia, and Europe, and of the territories renamed after the last wars [Augsburg: Bodenehr, 1720]), there is a group of children playing together, and the reader has made sure that their nakedness is properly covered.

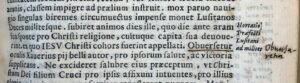

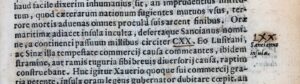

That some books were thoroughly read is suggested by the corrections made by knowledgeable readers. The best example of this kind of meticulous revision is found in an edition of Orazio Torsellino’s (1545–99) De vita Francisci Xaverii qui primus e Societate Iesu in Indiam & Iaponiam Evangelium inuexit, libri sex (Six books on the life of Francis Xavier, who was the first Jesuit to bring the Gospel to India and Japan [Rome: Zanetti, 1596]). As with today’s books, it was practically impossible to eliminate all typos, and readers could not help but notice them. On page 123, the philological reader underlined an “obversetur” and substituted it with an “obversaretur.”[38] The rest of the passage is written in the imperfect subjunctive, as in reported speech, so the change is correct.

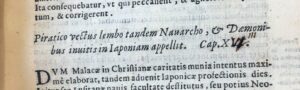

Finally, there was a third type of correction made by readers that revealed the attention and care taken when reading the content, almost as if they were professional copyeditors. One meticulous reader, for example, corrected the number of a chapter of the third book “Piratico Vectus lembo tandem Navarcho, & Daemonibus invitis in Iaponiam appellit” (Sailing on a pirate ship, Xavier finally lands in Japan, though the captain and the devils were in opposition) from “XVI” to “XVIII.” Was he right? Yes, because in consulting other versions of Torsellino’s life of Xavier, we see that this book[39] does not include a chapter 19 and finishes with this very section.

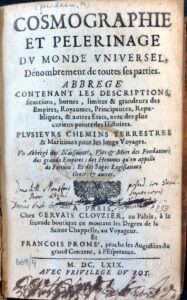

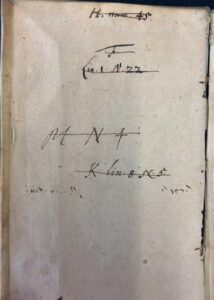

Finally, all of these books had ex libris, stamps or handwritten notes mentioning their provenance and history—which were sometimes long and tortuous. These inscriptions could be very well written and clear, like this one in the Chartae geographicae: Ex liberali donatione Nobilis & Consultissimi Domini, Domini Joannis […] Domûs Probationis Societatis IESU Moguntiae (Geographical maps: Generously donated by the noble Lord Johannes Braun […] to the probation house of the Society of Jesus in Mainz). But their provenance could include many changes of ownership, and traces of this trail of custody can be much more difficult to read. The library’s edition of P. Jourdain’s Cosmographie et pèlerinage du monde universel (Cosmography and pilgrimage of the universal world [Paris: Clovzier et Prome, 1669])[40] shows many owners in sequence, with the more recent ones canceling the traces of the previous ones and almost filling up the frontispiece.

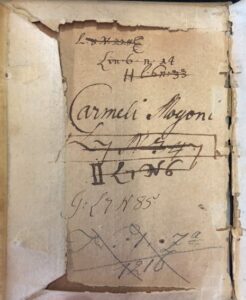

The same happens with the inner parts of this book, edited by the already mentioned Torsellino and once again about Francis Xavier, but this time with reference to his epistolary: Francisci Xaverii epistolarum libri quatuor (The four books of Francis Xavier’s letters [Mainz: Apud Lippium, 1600]). The book contains a sequence of call numbers testifying to the many times it was moved in the early modern period and in the more recent libraries that held it for some time. Both pictures show how the owners shelf marks changed from time to time.

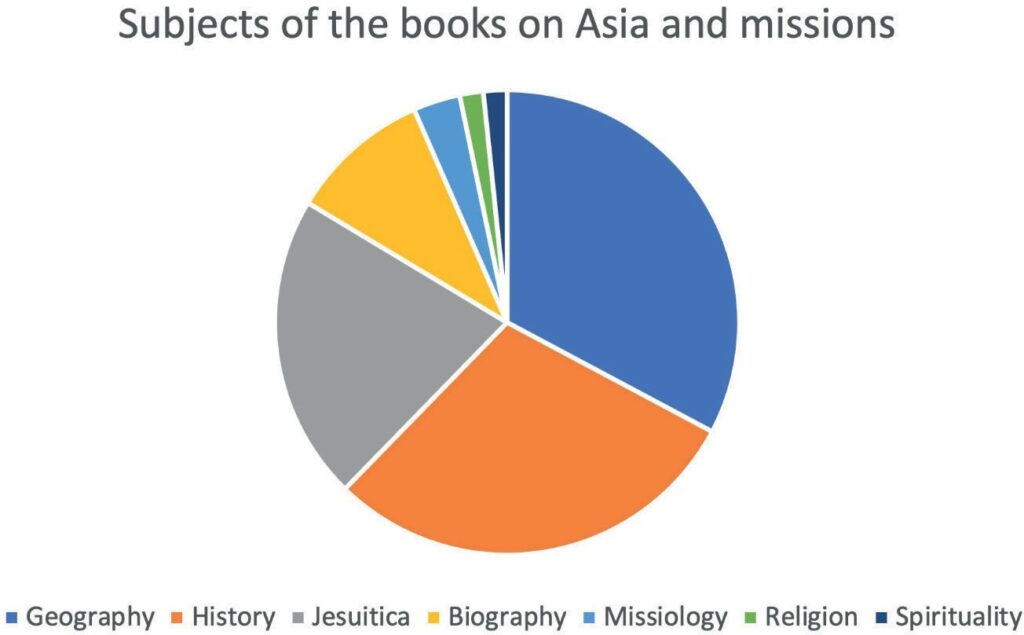

The books on the missions and on Asian civilizations covered different topics, which this graphic groups under a few main areas:

Sixty percent of the authors were Jesuits, thirty percent of the authors were not. As for books on the farthest countries in the world, there are numerous books written by Jesuits, who interpret these territories mainly as missionary destinations. They focus on the history and geography of the countries, mostly after but also before the Jesuits started planning missions there. Often these publications are the most up to date and precise ones available on the topic because the Jesuits were part of the most documented knowledge networks of the early modern period. The most renowned books available to the Jesuits in the Mainz novitiate were De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas suscepta (On the Christian mission in China [Augsburg: Mang, 1615]) by Matteo Ricci (1552–1610); Lettere del Giappone dell’anno MDLXXII: Scritte dalli reverendi Padri della Compagnia di Giesú (Letters from Japan written by the reverend Jesuit fathers in the year 1572 [Rome: Zanetti, 1579]), collected and edited by the Society of Jesus; and the Novus Atlas Sinensis (New Chinese atlas [Amsterdam: Blaeu, 1655]) by Martino Martini (1614–61).

But the travels and geographical discoveries that Jesuit libraries contained were also described by non-Jesuits, as in the case of Mercator’s Atlas sive Cosmographicae meditationes: De fabrica mundi et de fabricati figura (Atlas or cosmographical medita- tions: On the creation and form of the world [Amsterdam: Hondius, 1613]); Warhafftige Relation: Der dreyen newen unerhoerten seltzamen Schiffart so die Hollaendischen und Seelandischen Schiff gegen Mitternacht drey Jar nach einander als Anno 1594. 1595. und 1596. verricht. Wie sie Nortvvegen, Lappiam, Biarmiam, und Russiam, oder Moscoviam […] umbsegelt haben (True account: The three new, unheard-of, strange naval journeys that the Dutch performed in the three years 1594, 1595, and 1596 and how they circumnavigated Norway, Lapland, Bjarmaland, and Russia, or Moscovia [Nuremberg: Hulsius, 1598]); and Warhafftiger Bericht von den Newerfundnen Japponischen Jnseln vnd Koenigreichen auch von anderenzuvor vnbekandten Jndianischen Lande (True account of the newly discovered Japanese islands and kingdoms, and also of other previously unknown territories in the Indies [Fribourg: Gemperlin, 1586]).[41] Some of these books were written by geographers and travelers who were not even Catholic, but it was important for the Jesuit library to keep them because they offered accounts of the recently discovered areas of the world, often for the first time.

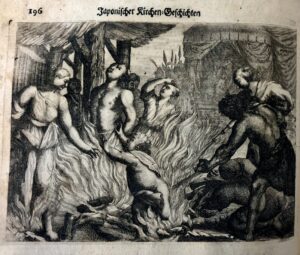

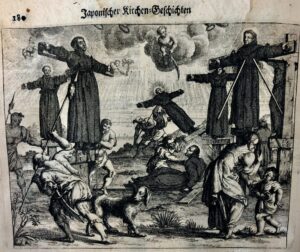

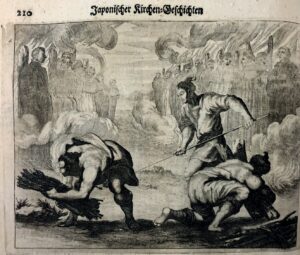

The present research tried to identify books related to travels, specifically in the East. Asia and martyrdom emerged as an inseparable combination, as shown in titles like De Christianis apud Iaponios triumphis sive de gravissima ibidem contra Christi fidem persecutione (Of the triumphs of the Christians among the Japanese, or of the most severe persecution there against the Christian faith [Munich: Sadeler, 1623]) by the Flemish procurator of the vice-province of China Nicolas Trigault (1577–1628) and De rebus Iaponicis historica relatio (A historical account of what happened in Japan) by the Portuguese Luís Froís (1532–97), one of the first Jesuits operating in Japan. Some of the sections of the latter book are especially relevant: the first one describes De gloriosa morte 26. crucifixorum, that is, it focuses on the martyrs of Nagasaki in 1597; while the third part informs the reader about De rebus per Iaponiam anno 1596 a Patris Societatis Iesu durante persecutione gestis, or the story of the persecutions suffered by the Jesuits from the first anti-Christian decrees issued by the Japanese authorities at the turn of the sixteenth century. The Flemish Cornelius Hazart (1617–90) is the author of Die Asiatische Länder: Japon, China, Tartaria, Mogor, und Bisnagar (The Asiatic countries: Japan, China, Tartaria, Mogor, and Bisnagar [Vienna: Voigt, 1678]). The books contain dozens of images representing the most horrific tortures, confirming once again how the Asian continent was inextricably intertwined with the idea of martyrdom—especially in the case of Japan, one of the destinations young Jesuits from all over Europe most longed for.

Digital Humanities Project and Conclusions

The final part of this paper and its conclusion focus on further outcomes of projects like this one on Jesuit books on East Asian missions. In 2018, Prof. Kathleen M. Comerford of the Georgia Southern University developed the European Jesuit Libraries Provenance Project (EJLPP),[42] aimed at identifying and describing all the books from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries once owned by Jesuit structures in Europe. The EJLPP involves different institutions, scholars from all around the world, and interns of the Georgia Southern University. The database is open access, and collaborations are sought with students interested in public history, the history of books, and Jesuit history.

One of its future goals will be to “trace the paths of individual books, the prominence of specific printers, and the distribution of given editions.”[43] The project employs different approaches: first of all, “comparative,” because it is based on research on Jesuit libraries all over Europe. Second, it has an “intellectual” perspective because studying libraries also means focusing on cultural history, the production of knowledge, and the ability of different strata of early modern society to access books. Finally, it is also “longitudinal, exploring the impact of the educational work of one of the most prominent of the Catholic religious orders.”[44]

Besides students, scholars are also invited to take part in the project. This is why part of the research at the Mainz libraries ended up in the collection of data on the Jesuit books regarding the East Asian missions.[45] The data included where the books are currently preserved, several facts about their authors (name, religious order, when and where he was born and died), detailed information about the editions (when, where, and by whom it was published and in which languages), and the subject matter of the publication. The most interesting data, even if hard to discover, concern the prove- nance of the book: Which Jesuit institution owned it? How did it acquire it? To which other owners did the book pass?

Another fascinating aspect of the EJLPP is the rich collection of images that collaborators are asked to collect. They have to focus most of all on the parts of the book that reveal its various owners—sometimes a religious order, sometimes an individual person, sometimes both—and its passage through space and time. All the photos are available online.[46] In some cases, the writings on the first pages and on the frontispieces are canceled and scribbled over so many times that it is almost impossible to read them entirely.

Digital humanities projects are very popular at the moment, but they post two great risks. They can be seen as living organisms: although they often start with promising goals, the original aims are never met, and such projects ultimately die a “natural death” after the input of the first group of data. Second, it is hard to find contributors who work on online databases on a professional, ongoing basis.[47] Prof. Comerford and her project show that research on Jesuit libraries can be very fruitful. It can be conduct- ed as case-studies, as with this project on the library of the Jesuit novitiate in Mainz, or the work can be done in a comparative mode. Further research on Jesuit libraries, also based on the data already collected in projects like the EJLPP, could investigate and compare libraries of different empires, with different languages and perspectives. Studying libraries allows us to understand the relationship between reading, teaching, learning, and printing. In general, the schools of the Society of Jesus were among the best in Europe, not only for future Jesuits. Library collections show what influenced the Jesuits’ educational strategies—which is especially important in cases like that of Germany, where Catholicism was not the most common religion, unlike in Portugal, Spain, and Italy.

These goals line up with the original aim of this current research project: getting to the roots of the missionary vocations of so many Jesuit petitioners for the East In- dies. The motivations can be studied very well in their Indipetae letters, but knowing on which books these motivations may have been based suggests the value of further in-depth analysis of all the data collected in the library of the Jesuit novitiate of Mainz.

Notes:

[1] On the role of Mainz and its Jesuit novitiate, see Martina Rommel, “Mainz: Jesuiten,” in Klöster und Stifte in Rheinland-Pfalz, http://www.klosterlexikon-rlp.de//rheinhessen/mainz-jesuiten.html (accessed June 27, 2023).

[2] ReIReS is the acronym for Research Infrastructure on Religious Studies, which has since been renamed as Resilience: Religious Studies Infrastructure (https://www.resilience-ri.eu [accessed June 27, 2023]), a consortium led by the Fondazione per le Scienze Religiose Giovanni XXIII, together with eleven other institutions in Europe. On the experience of the ReIReS fellowship, which allowed the writing of the present essay, see the blogpost https://reires.eu/4363/how-elisa-frei-experienced-the-reires-scholarship-in-times- of-corona/28/ (accessed June 27, 2023). The author expresses her gratitude to the local intermediator Alexandra Nusser for her professionalism and friendliness, and Christoph Nebgen, who advised (and still advises) her on the best ways to explore Jesuit sources in Mainz. She also thanks Paolo Aranha for the suggestions given when thinking about a ReIReS research project, and Seth Meehan, Claude Pavur, and Francisco Malta Romeiras for helping her in the last phases of the revision of the present essay.

[3] The novitiate and its library became the location of the diocesan seminary, and this is why some of the books of the novitiate ended up in the Martinus Bibliothek.

[4] For an updated overview on Indipetae and a complete bibliography about them, see Elisa Frei, Early Modern Litterae Indipetae for the East Indies (Boston: Brill, 2023).

[5] On the collection of rare books, the so-called rara, of Mainz, see Annelen Ottermann, Rara wachsen nach: Einblicke in die Rarasammlung der Wissenschaftlichen Stadtbibliothek Mainz (Mainz: Landeshauptstadt Mainz/Bibliotheken der Stadt Mainz, 2008), where many rare volumes are presented and their frontispieces have been photographed. On one of the most famous books on the Eastern missions preserved there, see also Christoph Nebgen, “Renward Cysat und sein ‘Warhafftiger Bericht von den Newerfundenen Japponischen Inseln und Königreichen,’” Bibliotheken heute 13, no. 2 (2017): 79–81.

[6] When he visited the Jesuit library of Solothurn (currently in Switzerland) in the mid-1750s, Gibbon complained that it only contained works produced by their own members, and the worst among them (quoted in Jan Holt, “Die Solothurner Jesuitenbibliothek [1646–1773] und ihre Gönner: Die Bibliothek Franz Haffners und weitere Schenkungen und Vermächtnisse,” Jahrbuch für Solothurnische Geschichte 80 [2007]: 247–76, here 252).

[7] On the missionary vocation of German Jesuits of the early modern period, see Christoph Nebgen, Missionarsberufungen nach Übersee in drei deutschen Provinzen der Gesellschaft Jesu im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert (Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, 2007).

[8] The subject of Jesuit libraries is wide-ranging and can be approached from various perspectives. For an updated and complete introduction, see Noël Golvers, “Jesuit Libraries in the Old and the New Society of Jesus as a Historiographical Theme,” in Engaging Sources: The Tradition and Future of Collecting History in the Society of Jesus (Proceedings of the Symposium Held at Boston College, June 11–13, 2019), ed. Cristiano Casalini, Emanuele Colombo, and Seth Meehan (Chestnut Hill, MA: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 2021), 1–19, which contains an extensive and thematic bibliography from p. 3 onward (https://www.bc.edu/ content/dam/bc1/top-tier/centers/iajs/Research/symposium-proceedings-2019/19symposia-golvers.pdf [accessed June 27, 2023]). See also the special issue of the Journal of Jesuit Studies edited and introduced by Kathleen Comerford, “Jesuits and Their Books: Libraries and Printing around the World,” Journal of Je- suit Studies 2 (2015): 179–88; the issue is available open access at https://brill.com/view/journals/jjs/2/2/ jjs.2.issue-2.xml (accessed June 27, 2023). See also Natale Vacalebre, Per una storia delle antiche biblioteche della Compagnia di Gesù: Con il caso di Perugia (Florence: Olschki, 2016) and Brendan Connolly, “Jesuit Library Beginnings,” Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy 30, no. 4 (1960): 243–52.

[9] As quoted from Canisius’s letter in Golvers, “Jesuit Libraries in the Old and New Society,” 1.

[10] On Jesuit libraries in Germany, see for instance Wilfried Enderle, “Die Jesuitenbibliothek im 17. Jahrhundert: Das Beispiel der Bibliothek des Düsseldorfer Kollegs 1619–1773,” Archiv für Geschichte des Buchwesens 41 (1994): 147–213.

[11] Holt, “Die Solothurner Jesuitenbibliothek,” 250.

[12] “Struttura portante dell’intero curriculum di docenti e allievi”; Valentino Romani, “‘Dispersione’ vs ‘disseminazione’: Note e materiali per una storia delle biblioteche gesuitiche,” in Le biblioteche private come paradigma bibliografico, ed. Fiammetta Sabba (Rome: Bulzoni, 2008), 155–81, here 160.

[13] Golvers, “Jesuit Libraries in the Old and New Society,” 19.

[14] On the migration of knowledge between Europe and the East, see Noël Golvers, Libraries of Western Learning for China: Circulation of Western Books between Europe and China in the Jesuit Mission (ca. 1650–ca. 1750), vol. 1, Logistics of Book Acquisition and Circulation (Leuven: F. Verbiest Institute, 2012).

[15] Golvers, “Jesuit Libraries in the Old and New Society,” 15. See also Francisco Malta Romeiras, “Researching the Modern Jesuit Library: A Case Study from Portugal’s Campolide Library,” Archivum histori- cum Societatis Iesu 182 (2022): 495–540, esp. 500–1.

[16] There are also instructions about libraries in the Constitutions (for instance MHSI, MI Const. I. Rome: Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu, 1934, 37) and in local documents like the Regulae Conimbricenses (1545) elaborated by the Portuguese Simão Rodrigues, one of Ignatius’s first companions. The latter docu- ment is edited in MHSI, Regulae Societatis Jesu (1540–56), Rome, 1948, 58–61; for reference, see Natale Vacalebre, “‘Como un hospital bien ordenado’: Alle origini del modello bibliotecario della Compagnia di Gesù,” Histoire et civilisation du livre 10 (2014): 51–68, here 57ff.

[17] “Ne nostri copia librorum, sine quibus milites inermes esse videntur, careant, optandum esset, ut aliquis reditus annuus ampliandae bibliothecae attribuatur, qui in alios usus non esset convertendus”; chapter 8 (De libris) of the 1586 draft of the Ratio studiorum. See Ratio studiorum et institutiones scholasticae Societatis Jesu per Germaniam olim vigentes, G. M. [Georg Michael] Pachtler, t. 2, Berlin, 1887, Monumenta Germaniae Paedagogica 5, 178ff, quoted in Ernst Manfred Wermter, “Studien und Quellen zur Geschichte der Jesuitenbibliotheken in Mainz 1561–1773,” in De Bibliotheca Moguntina: Festschrift der Stadtbibliothek Mainz zum 50jährigen Bestehen ihres Gebäudes Rheinallee, 1962, ed. Jürgen Busch (Mainz: Stadtbibliothek Mainz, 1963), 51–70, here 61.

[18] Wermter, “Studien und Quellen,” 61.

[19] “Supremus bibliothecarius […] ut regulae et speciales circa bibliothecam ordinationes studiose observentur […] eam saepius per annum visitabit; quotannis inquirit specialiter in librum, in quo adnotantur externi, quibus aliquando libri dantur accomodato, it si qui ex illis nondum sunt restituti repetantur, ne paulatim in oblivionem veniant et perdantur. Curabit etiam, ut in bibliotheca novis authoribus instruatur. Catalogum deinde tempore nundinarum, si haberi possit, et officinas bibliopolarum lustrabit […] Clavem bibliothecae apud se retinebit, nec ullum patietur librum se inconsulto ex bibliothecae auferri”; Ratio studiorum et institutiones scholasticae Societatis Jesu per Germaniam olim vigentes, G. M. Pachtler, t. 3, Berlin, 1890, Monumenta Germaniae Paedagogica 9:332ff., quoted in Wermter, “Studien und Quellen,” 61.

[20] Books could be bought, but they were also very often donated or exchanged between Jesuit institutions that possessed double copies. See Natale Vacalebre, “I canali di acquisizione libraria negli ordini di chierici regolari: Il caso della Compagnia di Gesù,” Bibliothecae.it 3, no. 2 (2014): 187–204.

[21] See rules 16 and 17 of the Regulae rectoris, and rule 29 of the Regulae praefecti studiorum (Ratio atque institutio studiorum Societatis Jesu [Mainz: Balthasar Lippius, 1600]).

[22] Vacalebre, “Como un hospital,” 58. See also Dominique Julia, “La constitution des bibliothèques des collèges: Remarque méthodique,” Revue d’histoire de l’église de France 83 (1997): 145–61.

[23] On Possevino’s library project, see Piero Innocenti, “Il sogno di Possevino: una Bibliotheca Selecta (senza pareti),” Culture del testo e del documento 44, no. 37/1 (2014): 43–66.

[24] Wermter, “Studien und Quellen,” 52.

[25] For a history of the Jesuits in Mainz, see Wermter, “Studien und Quellen” and Fritz Arens, “Das Mainzer Jesuitennoviziat (Ehemaliges Invalidenhaus),” Mainzer Zeitschrift 48–49 (1953): 152–70, and the more recent Michael Müller, “Die Jesuiten,” in Handbuch der Mainzer Kirchengeschichte, ed. Friedhelm Jürgensmeier (Würzburg: Institut für Mainzer Kirchengeschichte, 2002), 3:1, 642–99, https://bistummainz.de/ kunst-gebaeude-geschichte/kirchengeschichte/veroeffentlichungen/handbuch-der-mainzer-kirchenges- chichte/ (accessed July 9, 2023).

[26] See Peter Sjörkvist, “On the Order of the Books in the First Uppsala University Library Building,” Journal of Jesuit Studies 6 (2019): 315–26.

[27] Wermter, “Studien und Quellen,” 55n3.

[28] For an image of the catalog, besides the manuscript itself, see Wermter, “Studien und Quellen,” 57.

[29] See p. 203 of the Catalogus universalis (1674) as reproduced in Wermter, “Studien und Quellen,” 59.

[30] For a map see Arens, “Das Mainzer Jesuitennoviziat,” 156.

[31] Arens, “Das Mainzer Jesuitennoviziat,” 157–58.

[32] Wermter, “Studien und Quellen,” 60.

[33] The most conspicuous library collections of the German-speaking countries of the Society of Jesus were in fact Mainz, Ingolstadt, and Vienna (Holt, “Die Solothurner Jesuitenbibliothek,” 265).

[34] Golvers, “Jesuit Libraries in the Old and New Society,” 19.

[35] This statistic is drawn from Holt, “Die Solothurner Jesuitenbibliothek,” 266ff., but the research conducted in Mainz confirmed that the situation was the same there as well. For other German cases, see the following: Jürgen Coenen, “Die Bibliothek des ehemaligen Jesuitenkollegs in Münster,” in Bibliothek in vier Jahrhunderten, ed. Helga Oesterreich (Münster: Aschendorff, 1988), 11–49; Wilfried Enderle, “Die Jesuitenbibliothek im 17. Jahrhundert: Das Beispiel des Düsseldorfer Kollegs 1619–1773,” Archiv für die Geschichte des Buchwesens 14 (1994): 147–213; Dieter Breuer, “Die Aachener Jesuitenbibliothek,” Geschichte im Bistum Aachen 6 (2002): 55–79.

[36] See below.

[37] On scientific censorship, see Francisco Malta Romeiras, “Putting the Indices into Practice: Censoring Science in Early Modern Portugal,” Annals of Science 77 (2020): 71–95, and Hannah Marcus, Forbidden Knowledge: Medicine, Science, and Censorship in Early Modern Italy (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2020), both underlining the fact that censored books were read nonetheless.

[38] Obvers[ar]etur oculis Xaverius pij belli autor, pro ipsorum salute, ac Victoria supplicans (Xavier appeared before their eyes as one promoting the holy war, praying for their safety and victory).

[39] See for instance the edition printed in Antwerp in the typography of Ioachim Trognaesi in 1596, 278.

[40] Full title continues as Dénobrement de toutes ses parties abbrege’ contenant les descriptions, situations, bornes, limites & grandeurs des empires, royaumes, principautes, republiques, & autres états, avec des plus curieux points des histoires; plusieurs chemins terrestres & maritimes pour les longs voyages (Enumeration of all the abridged parts containing the descriptions, situations, limits, and sizes of the empires, kingdoms, principalities, republics, and other states, with the most curious historical points; several land and sea routes for long trips).

[41] On this volume, see Nebgen, “Renward Cysat und sein ‘Warhafftiger Bericht.’”

[42] “European Jesuit Libraries Provenance Project: Jesuit Books and Libraries in Europe, 1540s–1770s,” https://www.jesuit-libraries.com (accessed June 27, 2023).

[43] Kathleen Comerford, “The European Jesuit Libraries Provenance Project,” Journal of Jesuit Studies 7 (2020): 299–310, here 308.

[44] Comerford, “European Jesuit Libraries,” 309.

[45] As explained in the blogpost https://www.jesuit-libraries.com/single-post/books-on-asia-as-sources- for-jesuit-missionary-vocation-guest-post-by-elisa-frei (accessed June 27, 2023).

[46] The photos can be accessed via the following link: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/jesu- it-lib/ (accessed June 27, 2023).

[47] A database that successfully involves thousands of high school and university students in Europe and the Americas is the Digital Indipetae Database, which is being developed by the Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies (IAJS) at Boston College. The students who want to collaborate (for an internship, in preparation of their dissertation, during special projects at school) receive a selected group of Litterae indipetae to transcribe; their work is supervised by an IAJS project assistant, who revises the transcriptions and uploads them to the website. This way, the critical edition of all the twenty-two thousand Litterae indipetae written by Jesuits in the early modern period and after the restoration of the order in 1814 will be accessible online in the coming years. On the value of the project also as a teaching tool, see Elisa Frei, “Minds and Hearts and Digital Data: Collaborative Learning with Jesuit Manuscripts and Databases,” Jesuit Higher Education: A Journal 11, no. 2 (2022): 95–104.

- Title: Martyrdom in the Library: The Books of the Early Modern Jesuit Novitiate in Mainz (Germany)

Author: Elisa Frei

Article Type: Research Article

DOI: 10.51238/ISJS.2022.02

Language: English

Pages: 1–14

Keywords: - Volume: 2

- Issue: 1, special issue

- In: The Jesuits and the Church in History

- Editors: Claude Pavur, S.J., Barton Geger, S.J., and Robert Gerlich, S.J.

- In: International Symposia on Jesuit Studies

Publication Date: 30 November 2023

Last Updated: 30 November 2023

Publisher: Institute of Jesuit Sources

E-ISSN: 2766-0644

ISBN: 978-1-947617-19-3

APA

Frei, E. (2023). Martyrdom in the library: The books of the early modern Jesuit novitiate in Mainz (Germany). In C. Pavur, S.J., B. Geger, S.J., & R. Gerlich, S.J. (Eds.), The Jesuits and the Church in history (Proceedings of the symposium held at Boston, August 1–4, 2022) [Special issue]. International Symposia on Jesuit Studies, 2(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2022.08

CMOS

Frei, Elisa. “Martyrdom in the Library: The Books of the Early Modern Jesuit Novitiate in Mainz (Germany).” In “The Jesuits and the Church in History (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Boston, August 1–4, 2022),” ed. Claude Pavur, S.J., Barton Geger, S.J. and Robert Gerlich, S.J., special issue, International Symposia on Jesuit Studies 2, no. 1 (2023): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2022.08.

MLA

Frei, Elisa. “Martyrdom in the Library: The Books of the Early Modern Jesuit Novitiate in Mainz (Germany).” The Jesuits and the Church in History (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Boston, August 1–4, 2022), edited by Claude Pavur, S.J., Barton Geger, S.J., and Robert Gerlich, S.J., special issue of International Symposia on Jesuit Studies, vol. 2, no. 1, 2023, pp. 1–18. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2022.08.

Turabian

Frei, Elisa. “Martyrdom in the Library: The Books of the Early Modern Jesuit Novitiate in Mainz (Germany).” In “The Jesuits and the Church in History (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Boston, August 1–4, 2022),” ed. Claude Pavur, S.J., Barton Geger, S.J., and Robert Gerlich, S.J., special issue, International Symposia on Jesuit Studies 2, no. 1 (2023): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2022.08.

© Institute of Jesuit Sources, Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, All Rights Reserved