Research Article

Engaging Sources: The Tradition and Future of Collecting History in the Society of Jesus

Section 1. Jesuit Sources of Self-identification

Part 4 — Lost Sources Found

Sketching the Historical Soundscape of Sacred Music in China through Jesuit Sources

Hong, Li-Xing. “Sketching the Historical Soundscape of Sacred Music in China through Jesuit Sources.” In “Engaging Sources: The Tradition and Future of Collecting History in the Society of Jesus (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Boston, June 11–13, 2019),” ed. Cristiano Casalini, Emanuele Colombo and Seth Meehan, special issue, International Symposia on Jesuit Studies 1, no. 1 (2023): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2019.14.

Introduction

Starting with the arrival and the work of Michele Ruggieri (1543–1607) and Matteo Ricci (1552–1610) in the late Ming Dynasty of China, the Society of Jesus has been one of the most influential religious orders to evangelize in China. These Jesuits from Europe were equipped with profound knowledge in a diverse range of disciplines and contributed significantly to the advancement of arts and science in China. Nevertheless, their proficiency in these different disciplines was supplementary to their real work, which was to convert and catechize the Chinese faithful. This essay investigates the significant contribution of the Jesuits in China to the introduction and promotion of Catholic sacred music that constituted an integral part of the liturgy (Mass and Divine Office) and of paraliturgical or extraliturgical practices, which is a subject that has not been fully explored.

This essay consists of three parts, which together try to establish the historical situation related to the repertoire of sacred music and liturgical practices introduced to the Chinese by the Jesuits. Part One of the article presents the original sources, ranging from the correspondence, manuscripts, and the publications of chant books and hymnals in China, pertinent to the introduction of Catholic sacred music, facilitated through Jesuit missionaries who were well-versed in music. Part Two investigates the content of archives and documents and establishes three categories of sacred music most commonly used in China. Part Three is an attempt to re-con- struct the historical soundscape of sacred music in China, especially how the three different types of music were applied in liturgical and devotional contexts.

I. Jesuit Sources Related to Sacred Music

The Jesuits have been very attentive to the preservation of documents and archives in the missionary areas in which they worked all over the world. These files are kept and well-maintained in the missionary provinces, as well as the main archives in Rome. In addition to records of historic times, places, and events, individual priests might have a personal folder of related files, some of whom have kept extensive records or maintain voluminous correspondence, while other individuals might have been sparer in their record-keeping. Despite the fact the documents about music are comparatively scarce and scattered, the profile of the Jesuits’ efforts in the development of liturgical music in China can be reconstructed through archival documents following four main directions: Jesuit musicians in missions, personal correspondence of Jesuit missionaries, manuscripts and publications of music scores, and graphic materials.

1) Agents: Jesuit Musicians in Missions

Let us examine a passage written by Benjamin Brueyre (1810–80), a French Jesuit evangelizing in Shanghai who wrote to his confrere back home. In the letter, he describes the celebration of Catholic rituals in the seminary he recently had established:

Our ceremonies of the Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament, without having the pomp of that which we see in France in the boarding schools, do not cease however to appear marvelous for the country. It will be much better when I can have a Priest who knows a little music with me; one will find here enough children to form a fairly complete choir.[1]

The excerpt reveals how the Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament was celebrated in the seminary near Shanghai. Despite the fact that it could not be as elaborately done in China as in France, for the Chinese people it was already a marvelous experience. At the same time, Fr. Brueyre regrets the fact that he does not have any Jesuit musicians to help him further sanctify the worship, especially when the Chinese children could have enriched the singing of the choir after they were properly trained. His description also acknowledges the significance of having missionaries with good music capability and how they could be conducive to the liturgical practices in missionary regions.

In fact, a good number of Jesuit missionaries who came to work in China during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties were talented musicians—Diego De Pantoja (1571–1618), Johann Adam Schall von Bell (1591–1666), Ferdinand Verbiest, (1623–88), Tomás Pereira (1645–1708), Florian Bahr (1706–71), Louis-Joseph Desrobert (1703–60), and Joseph-Marie Amiot (1718–93), just to name a few (Table 1 lists the Jesuit missionaries with musical ability and the time and place of their work in China). However, it is worth noting that with the exceptions of Desrobert and Amiot, the other Jesuit fathers did not leave behind many documents, writings, or records directly related to the practice of liturgical music. They were known for their cultural contributions and their roles in facilitating exchanges between the Chinese and the Western world, especially for their service in the imperial court.[2]

Name | Nationality | Period in China | Mission |

Diego de Pantoja 龐迪我 | Spanish | 1597–1618 | Beijing |

Johann Adam Schall von Bell 湯若望 | German | 1619–66 | Beijing |

Ferdinand Verbiest 南懷仁 | Belgian | 1658–88 | Beijing |

Tomas Pereira 徐日昇 | Portuguese | 1672–1708 | Beijing |

Karl Slavicek 嚴嘉樂 | Bohemian | 1716–35 | Beijing |

Florian Bahr 魏繼晉 | German | 1738–71 | Beijing |

Louis-Joseph Desrobert 趙聖修 | French | 1737–60 | Beijing |

Jean-Joseph-Marie Amiot 錢德明 | French | 1750–93 | Beijing |

Léopold Deleuze 婁良才 | Belgian | 1846–65 | Kiangnan |

Jean Loriquet 祿理格 | French | 1847–86 | Kiangnan |

François Ravary 藍廷玉 | French | 1856–91 | Kiangnan |

Hippolyte Basuiau 蘇念澄 | French | 1865–86 | Kiangnan |

Joannes Twrdy 戴爾第 | Silesian / German | 1867–1910 | Kiangnan |

Albert Wetterwald 萬其傑 | French | 1894–1942 | Zhili |

Table 1. Jesuit Missionaries with Musical Talent in the China Mission (not an exhaustive list)

After the restoration of the Society of Jesus in 1814, the Jesuit missionaries with musical talent who came to China made more effort in improving the practices of liturgical music and were more conscientious in writing about their work with music. Their efforts, nonetheless, have not been properly studied by scholars. During this period, a relatively high percentage of Jesuits in China came from French-speaking regions, including France and Belgium. The fact is reflected in the style and the repertoire of liturgical music and hymns introduced to the Chinese faithful. From the written records and published materials of this period analyzed below, we are given clues with which we can attempt to re-construct the soundscape of the Chinese Catholic church in the nineteenth and early twentieth century.

2) Personal Correspondence of Jesuit Missionaries

Jesuit missionaries’ correspondence with their relatives and friends, as well as their confreres is a great source for getting to know more about their missionary work in China. In a number of these letters, some missionaries give detailed accounts of the liturgical practices in China; these provide the first-hand material that help us enter into the world of the Catholic liturgy in the country. Some of these letters are only preserved in Jesuit archives and others may have been published in volumes of collected letters (for example, Lettres édifiantes et curieuses, Lettres de Vals, Lettres des nouvelles missions de la Chine, Lettres des Scholastiques de Jersey, Chine Ceylan Madagascar, etc.). In addition to these letters, the notes and narratives of missions in China can contain fragments of descriptions of sacred music in China.

3) Manuscripts and Publications of Music Scores

From documentary evidence and known publications, we can compile a list of works related to sacred music for the early stage of the Jesuits’ activity in China (please refer to Table 2). Among these works, Xiqin Quyi (西琴曲意)[3] and Tianyue Zhengyinpu (天樂正音譜)[4] contain verbal texts, but no music scores. Moreover, judging from the nature of the verbal texts, it is likely that these works are not written nor used for liturgical settings.[5] From the limited description of the four volumes of Chants sacrés (奏樂歌經典禮), we can assume that Fr. Desrobert’s works were compiled to be used for the liturgy, but unfortunately, these works have been lost. Among these documents, only Fr. Amiot’s Musique Sacrée (聖樂經譜)[6] presents specific music pieces used in the Catholic liturgy.[7]

Year | Title | Author | Notes |

1601 | Xiqin Quyi 西琴曲意 | Matteo Ricci 利瑪竇 | Text only |

ca. 1710 | Tianyue Zhengyin pu 天樂正音譜 | Wu Li 吳歷 | Text only |

1760 | Chants sacrés (4 volumes) 奏樂歌經典禮四卷 | Louis-Joseph Desrobert | Lost |

1779 | Musique sacrée 聖樂經譜 | Joseph-Marie Amiot | Manuscript |

Table 2. List of Sacred Music Related Works Published by Jesuits before the 19th century

After the mid-nineteenth century, the Jesuits started two in-house imprints in Xianxian (Sienhsien, 獻縣) and Shanghai (Zikawei, 徐家匯) and endeavored to more systematically publish chant books and hymnals. According to publication catalogues of these imprints, more than twenty hymnals were compiled and printed (please refer to Table 3).[8]

No | Year | Title | Imprint | Type[9] | Notes |

1 | 1855 | 西音唱經 (Xiyin changjing) [Chants in Western Tunes] | Zikawei | A |

|

2 | 1877 | 各式聖歌 (Geshi shengge) [Various Sacred Songs] | Zikawei | C | Text only |

3 | 1877/8 | 詠唱經文 (Chants sacrés à l’usage des missions) | Zikawei | A | Edited by Hippo- lyte Basuiau |

4 | 1893 | 聖教歌選(初版) (Shengjiao gexuan, 1st edition) [Songs for the Sacred Religion] | Sienhsien | C |

|

5 | 1893- 1900 | 詠唱經文 (Chants sacrés à l’usage des missions) | Zikawei | A | In 3 volumes |

6 | 1898 | 聖歌 (Shengge) [Sacred Songs] | Zikawei | C | Edited by Joseph Chen-liang |

7 | 1903 | 詠唱和音/詠唱經文和音 ( Chants sacrés. Accompagnement) | Zikawei | A | Manual for organ accompaniment |

8 | 1903 | 方言避靜歌十二則 (Ed. 2a.) (Fangyen bijingge shier ze) [12 Songs for Retreats in the Dia- lect] | Zikawei | C | Edited by Matthias Tchang |

9 | 1904 | 經歌摘要 (Cantus sacri ) | Sienhsien | A |

|

10 | 1907 | 詠唱經文撮要 (Extrait des Chants sacrés) | Zikawei | A | Edited by Simeone Lieou |

11 | 1909 | 聖教要理歌曲 (Shengjiao yaoli gequ) [Songs for Catechism of the Sacred Religion] | Zikawei | C | Edited by Firminus Chen |

12 | 1912 | 清音譜 (Qingyin pu) [Scores of Pure Music] | Sienhsien | B | In Gongche nota- tion |

13 | 1913 | 詠唱經文辣丁文 (Yongchang jingwen ladingwen) [Chants in Latin] | Zikawei | A |

|

14 | 1913 | 佘山聖母歌 (Sheshan shengmuge) [Hymn for Our Lady of Sheshan] | Zikawei | C | Edited by Lauren- tius Tchang |

| 15 | 1921 | 詠唱經文補遺 (Yongchang jingwen buyi) [Appended Edition of Chants sacrés à l’usage des missions] | Zikawei | A |

|

16 | 1921 | 聖若瑟及追思彌撒詠唱序文 (Prefationes cum cantu de Sancto Joseph et Defunctorum) | Zikawei | A |

|

17 | 1925 | 奉獻全家(學校)於聖心歌 (Canticum ad consecrationem fami- liae [aut scholae] SS Cordis Jesu) | Zikawei | C | Edited by Matthias Tchang |

18 | 1927 | 詠唱經文第二版 (Nouveaux Chants sacrés, 2e édition) | Zikawei | A | Edited by Candido Vanara and Achille Durand |

19 | 1935 | 詠唱經文第三版 (Chants sacrés, 3e édition) | Zikawei | A |

|

20 | 1936 | 經歌彙選 (Motecta et Cantica) | Sienhsien | C |

|

21 | 1936 | 降福經歌摘要 (Cantus pro Bene- dictione SS. Sacramenti) | Sienhsien | A |

|

22 | 1940 | 經歌摘要 (Cantus sacri ) | Sienhsien | A |

|

23 | s.d. | Excerpta e Kyriali seu Ordinario Missae et Antiphonario romano, ad usum Sinensium | [Sienhsien] | A | Edited by Julien Monget |

24 | s.d. | 增補聖教歌選 (Zengbu shengjiao gexuan) [Appended Edition of Chants for the Sacred Religion] | [Sienhsien] | C |

|

Table 3. List of Chant Books and Hymnals published by Jesuits (1855–1936)

The Jesuits from France, mostly belonging to the Paris Province and the Champagne Province, were put in charge of missionary work in the apostolic vicariates of Jiangnan 江南 (Kiang-nan) and Southeast Zhili 直隸東南 respectively. Therefore, the Jesuit Archives of the Province of France in Vanves[10] preserves most of these hymnals. The des Fontaines Jesuit Collection preserved at the Municipal Library of Lyon[11] also has a modest collection of chant books and hymnals edited by the Jesuits in China. The contents of these hymnals provide concrete musical texts that give a clearer idea of the types of songs sung by the Chinese Catholics during this time period.

4) Graphic Materials

The development of sacred music in China can be further visualized by graphic materials. One of the most prominent examples is a painting preserved at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France entitled, “Église du Beitang en vue plongeante, avec personnages en procession dans les jardins du Palais impérial.” The work, a Chinese painting done in the Western artistic style of the mid-eighteenth century, depicts the procession in the courtyard of Beitang Cathedral in Beijing, offering a rare visual source for us to “see” Chinese-style Catholic worship. The painting illustrates two rows of musicians lining up on two sides of the courtyard and all of them holding Chinese musical instruments in their hands.[12] This painting also indicates that Chinese instruments were used in Catholic rituals (very likely the Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament) to enrich the musicality of these ceremonies during the eighteenth century.

In addition, in the Jesuit archives of the Province of France in Vanves, pictures, postcards, illustrations published in journals, and other visual materials in different formats also showcase the scenario of worship and liturgies.

II. Three Types of Sacred Music in Chinese Catholic Missions

From the above-mentioned archival documents, especially from the content of locally published chant books and hymnals, three main categories of Catholic music used and developed in China can be established: Latin chants, chanted prayers in Classical Chinese, and hymns sung in the vernacular language.

A. Latin Chants

Before the reformation of the sacred liturgy promulgated by the Second Vatican Council (1962–65), the liturgy of the Catholic Church was celebrated in Latin throughout the world. Gregorian chant was considered the most authentic and most appropriate music to be used in liturgical settings. Therefore, for the European mis- sionaries who came to evangelize in China, Latin chants would be the main source of music to be used for the rituals. However, not much was written and preserved about this category of liturgical music in China before the mid-nineteenth century.[13] With the establishment of their own printing houses in Xianxian and Shanghai

in the late nineteenth century, Jesuit missionaries began to compile Latin chant books for the Chinese faithful. Chants sacrés à l’usage des missions (詠唱經文), first published in 1877 in Shanghai and Cantus Sacri (經歌摘要), first published in Xianxian in 1904, are the two most representative series of chant books, and each of the two went through several editions.[14] In missionary epistles, these Jesuits priests describe how they prepared liturgical settings and how they trained choirs, the majority of them consisting of children and seminarians in Shanghai and the neighboring regions, to sing Latin chants during the Mass and other rituals.[15]

The analysis of these publications also shows that the most frequently used Ordinaries of the Mass include Messe Royale by Henri Dumont,[16] Missa de Angelis, Missa IX (cum jubilo) and the Missa pro defunctis. The singing of the Proper of the Mass is limited to only the most important solemnities and feasts. Beyond the chants for the Mass, the second important group of chants printed are those used for the Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament and a few pieces for Vespers. The content of these chant books also indicates that the Mass, together with the Benediction and Vespers are the three most historically-important rituals for the Chinese faithful.

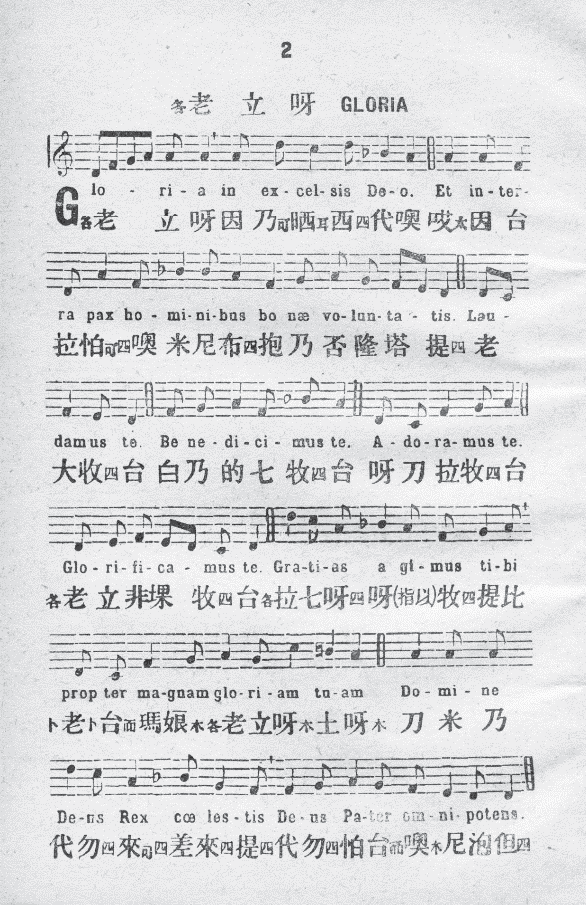

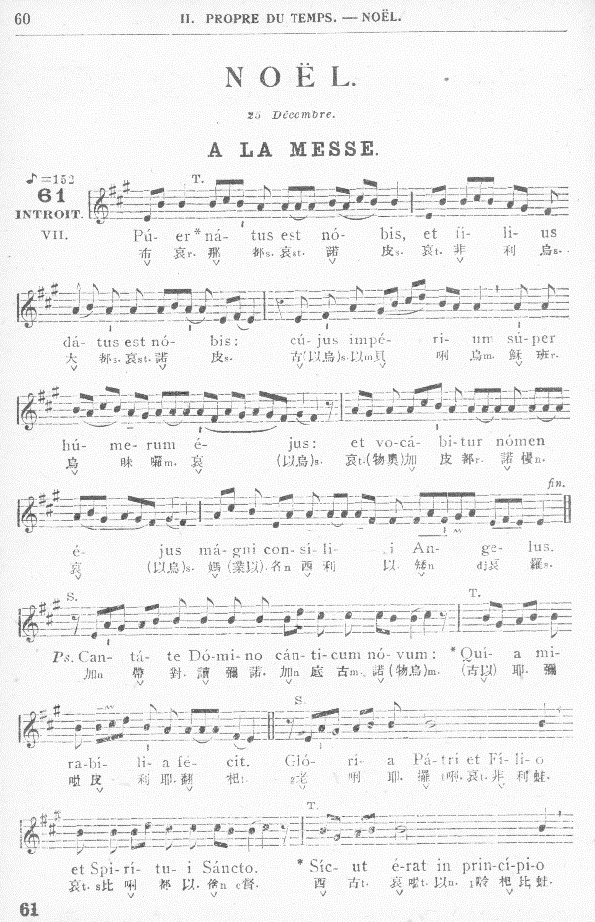

An ingenious measure taken in the publication of these chant books is the method of “transliteration,” with Chinese characters used to approximate the pro- nunciation of the Latin texts, as a special design to help the Chinese pronounce the Latin lyrics (Figures 1 and 2 show music scores taken from the chant books pub- lished in Xianxian and Shanghai which render the transliteration of Latin Gregorian chant in the regional dialects).[17] Nevertheless, the chant books do not include Chi- nese to explain the meaning of the texts of these chants. This omission points out that the compilers emphasize the practical usage of these chant books to help the Chinese faithful to sing instead of understanding the meanings of the texts.

Figure 1. “Gloria,” Cantus Sacri (1940), 2

Figure 2. “Puer natus,” Chants sacrés 3e édition (1935), 60

The majority of the pieces in these chant books are Gregorian chant, but there are also some Latin liturgical songs written in different musical styles. As Jesuits working in these two important missions mostly came from France, the non-Gregorian Latin pieces included in these two chant books also reflected their national identity. Some of the most prominent examples are the compositions of Fr. Louis Lambillotte, S.J. (1797–1855),[18] whose music reflects the period style and musical taste of his contemporaries. Despite the fact that Lambillotte never traveled to China nor worked in Asia, his presence and influence upon the development of Chinese sacred music is so strong that his works were not only introduced to the Catholics by his contemporary confreres but some of them were translated into Chinese and are still being sung today in churches in most of the Chinese-speaking areas.

B. Chanted Prayers in Classical Chinese

The second most prevalent type of sacred music used in China were chanted prayers in Classical Chinese. These prayers, originally written in Latin, were translated jointly by missionaries well-versed in Chinese and Chinese literati into classical Chinese and were set to Chinese-style melodies. For a long time, they played a vital role in nourishing the faith of the Chinese Catholics.[19]

Many Jesuits mentioned this unique type of chanted prayer, and how they were impressed by the religious sentiments Chinese people expressed through their singing. For example, back in the seventeenth century, Louis le Comte (1655–1729) described the chanting of the Chinese prayers and how it, though different from the European convention, bore the same potential to uplift the spirituality of the Catholics:

They sang in two choirs with a devotion which often made me wish to have the European Christians witness their piety. They know neither plainchant nor music like us; but they have made tunes which are not shocking and which seem to me much more bearable than the ones used in several communities of Europe.[20]

The missionaries who worked in China in the early seventeenth century had a chance to listen to the Buddhists’ chanted prayers in their gatherings and thought it was a praiseworthy practice. They commented that the prayers were chanted “with such order and harmony that they seem like the choruses of our European religious.”[21] It is highly possible that the missionaries were inspired by this Buddhist tradition and started the practice of chanting Catholic prayers in Chinese.

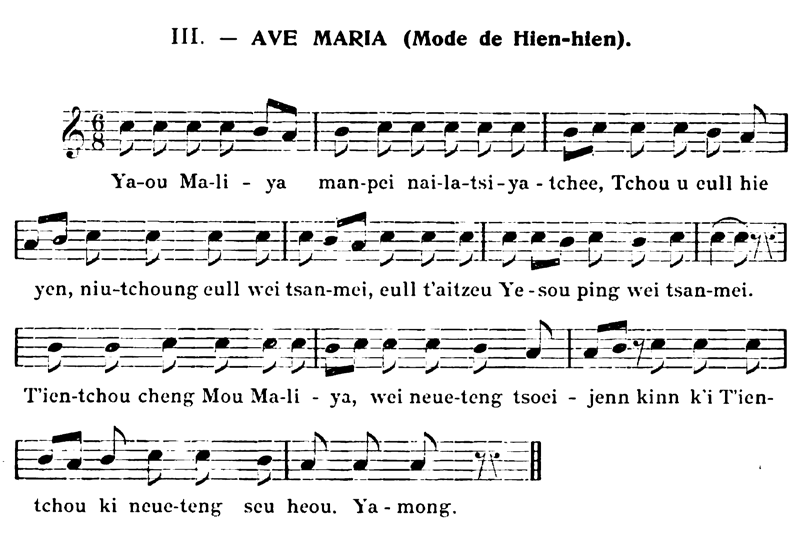

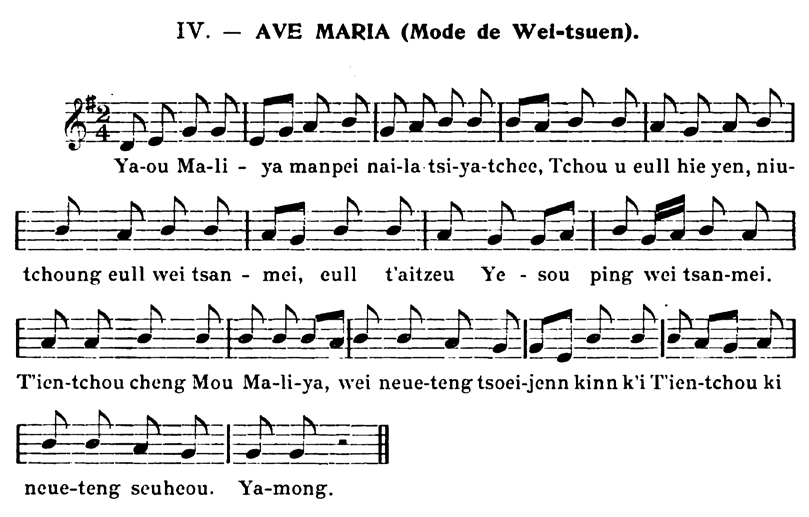

Most of these chanted prayers were passed down orally and were rarely notated. Fr. Wetterwald, who worked in Xianxian during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, explores this subgenre in an article.[22] These sung prayers were usually led by ling-king-ti (領經的), the counterpart of the cantor in Western liturgical services, while the congregation of the faithful together would render the prayer text into melody. The chants would vary because of the location and even the gender of the faithful. Fr. Wetterwald recorded the different melodies of the Ave Maria used in Weicun (魏村), where he served and the neighboring Xianxian (see Figures 3.1 and 3.2).

Figure 3.1. Ave Maria, Tune from Xianxian

Figure 3.2. Ave Maria, Tune from Weicun

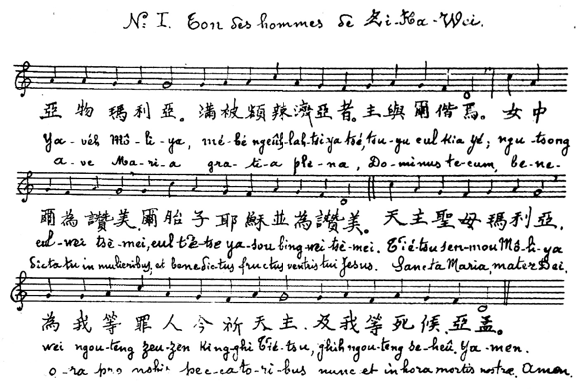

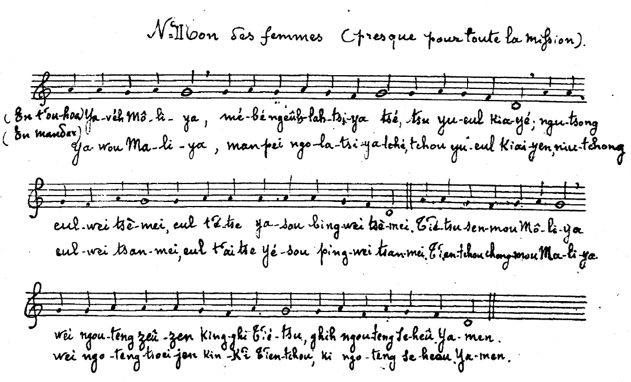

In the Jesuit Archives of the French Province in Vanves, there is a hand-written musical score entitled, “5 tons de l’Ave Maria,”[23] which contains five different additional versions of melodies for the Ave Maria sung and circulated in the Shanghai region. The following two examples of the Ave Maria from Zikawei with remarks designating the tone either for men or for women verify the statement of Fr. Wetterwald (Figures 4.1 and 4.2).

Figure 4.1. Ave Maria, Tune for Men of Zikawei © Archives jésuites (Vanves)

Figure 4.2. Ave Maria, Tune for Women of Zikawei © Archives jésuites (Vanves)

The documents of the Jesuit missionaries further point out the intricate variations for the same song that is sung on different occasions. These variations are parallel to the distinction between tonus simplex and tonus solemnis. There is a long tradition in the Roman Catholic Church to celebrate major solemnities and feast days with more solemn and elaborate music. In his letter written on the Eve of the Feast of the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus, Fr. Pierre-Martial Cibot, S.J. (1727–80) gives us an example of this practice in China:

… At four o’clock the first Mass is said, with music and symphony.[24] There is a motet at the exposition of the Most Blessed Sacrament; the symphony which is under the tent fills the intervals of the Masses; the one in the chapel has its [playing] time marked during each Mass.[25]

Thus, for major solemnities and feast days, choirs and instruments were used for the celebration of the Masses; they were not only interspersed into the intermissions between the different Masses during the day, but also at fixed parts of the Mass.

Within this background, the songs collected in Musique Sacrée (聖樂經譜) by Fr. Amiot can be better contextualized. His manuscript contains thirteen songs based upon Catholic prayers in Chinese “which our new Catholics sing on major feasts.”[26] Some of these prayers were probably used during the celebration described by Fr. Cibot. Besides the manuscript of Musique Sacrée, the only other Jesuit publication which collected Chinese sung prayers is Qingyin pu (清音譜) printed by Xianxian in 1913. Qingyin pu kept nine of the thirteen prayers from Musique Sacrée. Even though no more similar hymnals are located and identified from Jesuit sources, the overlap and similarity in the contents of Musique Sacrée and Qingyin pu tell us that the convention of Chinese sung prayers spanned over centuries and lay an important cornerstone upon which the Catholic faithful built their faith.

C. Hymns in the Vernacular Language

The third category is the hymns written in the vernacular language. These hymns, which served as an additional instrument for inculcating the faith in the common people, were written in simple language, sung to Chinese or Western melodies, and appeared relatively late in the development of the Chinese Catholic church.

The French Jesuits in Shanghai during the mid-nineteenth century were already writing about teaching the Chinese children to sing French or Chinese cantiques.[27] However, the hymnals with Chinese cantiques did not get published until the 1870s,

and the earliest of them, Geshi shengge (各式聖歌), contains only lyrics. Later on, two major series of hymnals, Shengge (聖歌) and Shengjiao gexuan (聖教歌選), emerged, with each of them going through several different editions. In these volumes, Chinese hymns composed following local musical styles are rarely included; the majority of the hymns are set as Western compositions, and most of them from France. These “imported” French songs are often traditional tunes or tunes composed by the contemporaries of the French missionaries.[28]

The following are two examples of Chinese sacred songs. The first one is based on O filii et filiae, a traditional song for Easter. In Shengge published in Shanghai, two editions of O filii et filiae are collected and the verbal text is an exact Chinese translation of the original Latin song. No. 30 continues to use the original Western Latin melody, while No. 29 is set to Chinese-style music following the prosody of the Chinese text (see Figures 5.1 and 5.2).

Figure 5.1. Yesu fuhuo ge (II), from Shengge (1926), p. 45

Figure 5.2. Yesu fuhuo ge (I), from Shengge (1926), p. 44

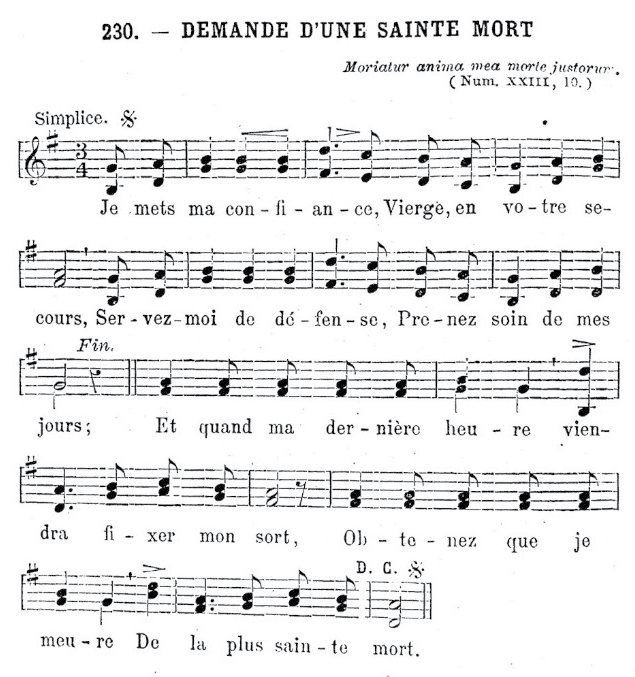

The second example is Je mets ma confiance composed by Louis Lambillotte, which was adapted into a Marian Hymn in Chinese, Yilai shengmu ge 依賴聖母歌 (Figures 6.1 and 6.2). In the original version,[29] the song has five verses, but the Chinese version has seven. Equally important to note is that only parts of the lyrics are faithfully translated into Chinese; the majority of the texts are either rewritten or taken or excerpted from other sources, for example pre-existing Marian prayers such as the Salve Regina (又聖母經 / 申爾福). Many of the lyrics for the Chinese cantiques follow this model. The editors took great liberty in keeping whatever they thought appropriate from the French version and rewrote whatever they deemed inadequate or ineffective; consequently, in terms of verbal texts, some of these songs are close to the original, but others are completely unrelated.

Figure 6.1. Je mets ma confiance in Recueil de Can- tique et de chants latins (1911)

Figure 6.2. “Yilai Shengmu ge” in Shengjiao gexuan

III. Historical Soundscape of Chinese Sacred Music

From the analysis of the Jesuit sources discussed above, we are able to construct a preliminary profile for the conception and practice of Catholic sacred music in China, an aspect of Catholic life that was inseparable from the liturgical services and devotions.

During the late Ming and early Qing Dynasties, Jesuit missionaries arrived in China to start their work of evangelization. While they knew the significant role of sacred music and its central position in liturgical settings, they did not have sufficient resources at hand to “transplant” the liturgical music practiced in their home countries in Europe to the far-away country in the East. Thus, there was not much that these missionaries could do, and they left few records about the practices of sacred music. Even when the Jesuits returned to Shanghai during the first half of the nineteenth century, they still lamented the scarcity of resources, because they found it almost impossible to put into practice liturgical music that met the standards for solemnities and feasts.[30] If later missionaries were challenged by so many difficulties, their predecessors who came to China two centuries earlier were con- fronted with many more unknown problems. Nonetheless, these missionaries were all aware of the fact that exotic ceremonies and rituals bear the potential to attract people to a religion and to arouse their curiosity to learn more about Christianity and the gospel of Jesus. To properly celebrate the Mass and other Catholic rituals when there were no resources to enact liturgical music following the norms set up in the West, they incorporated Chinese tunes and music familiar to the local people as a measure of expediency.

Consequently, the prayers translated into classical Chinese and set to relatively simple melodies became the most important type of sacred music during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries for the early Chinese Catholics. On occasions of devotions or religious gatherings when no priests were available to preside, the chanted prayers were situated right at the core of the activities of the faithful.[31] During the celebration of the Mass, the missionaries accommodated these chanted prayers so that the congregation could recite or chant at the appropriate time while the priest said a low mass.[32] This would enhance the sense of participation and understanding of the Catholic faithful when mass was celebrated in Latin, a language completely foreign to them. In other words, these chanted prayers filled up the hole left by the lack of Latin liturgical music used for Eucharistic celebrations. On occasions of major solemnities or feast days when more music should be used to create a solemn atmosphere, they would assemble an orchestra of Chinese musical instruments. These chanted prayers continue to nourish the Catholic faith and spirituality on Chinese soil and form a tradition that was not disrupted even during the most difficult times when Catholicism was banned officially.

When China reopened its doors to the Western world in 1842, the Jesuits returned to China. This time, they were better prepared to re-enact the solemn liturgical music from the Catholic Church of their home countries in the Chinese land. With the restoration of Gregorian chant in Europe, more missionaries received solid training in these chants that have been considered the authentic Church music since the medieval period. Concurrently, the Chinese Catholic Church started establishing seminaries. Areas with better resources were now able to have children’s choirs or choirs composed of seminarians whose education included Latin chants.

On top of Gregorian chant, Jesuit missionaries also imported contemporary hymns used in the Western world, which they translated into Chinese so that the Catholic faithful could sing and praise God in their mother tongue. Some of the earliest hymns were rendered with Chinese melodies, while others kept to the original tune. During the mid-nineteenth century, French Jesuits systematically introduced French cantiques, as well as other forms of sacred music. Chinese texts were set to these Western hymns and the number of these works increased rapidly. From the number of hymnals published during that period of time, even though the quality of the songs varies because of translation, it is clear that these sacred songs played a vital role in devotions and pastoral ministry. However, like the majority of French cantiques written during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that were abandoned and forgotten with the passage of time, most of these Chinese cantiques were inevitably doomed to oblivion. Only a very small number of them survive and remain in the repertoire of today’s hymnals.

IV. Concluding Remarks

From the different types of songs that were transplanted from a foreign source or grew out of the traditional Chinese local music, the complexity involved in the music practices in missionary regions is evident. On top of meeting the strict requirements of the Catholic liturgy, these Jesuit missionaries confronted challenges deriving from limited musical ability, scarcity of musical resources, and the strategies of evangelization, as well as other cultural factors. Nonetheless, they observed one single principle in choosing from the diverse music genres and forms: to help the person who sang these songs to better participate in the rituals so that they could appreciate the transcendental value and immerse themselves in the religious experience. From the hymnals and music-related documents preserved in different Jesuit archives, a rough soundscape of sacred music in China has been delineated, which allows us to witness the Jesuits’ efforts for inculturation and their achievement in spreading Christianity in China. In 1854, Fr. Pierre Fournier described to his brother the singing of prayers by the Chinese faithful early in the morning; this description might be the most authentic portrayal of the soundscape of Catholic music in China:

This must be a very pleasant concert in Heaven, that these thousands of voices who, from the morning, even before the song of the birds, rise on all sides of this pagan land, to praise the Lord and to thank him for his good deeds.[33]

Notes:

[1] “Les cérémonies de nos saluts du St Sacrement, sans avoir la pompe de celle que l’on voit en France dans les pensionnats, ne laissez pas cependant de paraître merveilleuses pour le pays. Ce sera beaucoup mieux encore quand je pourrai avoir avec moi un Père un peu musicien; on trouvera ici parmi les enfants de quoi former un chœur assez complet.” Benjamin Brueyre to a father from the same company, Chang-Haï, March 10, 1856, in Lettres des nouvelles missions de la Chine, vol. 1 (1841–46), 279.

[2] This article focuses on the discourse related to liturgical music. For the discussions and studies on the contribution of the Jesuits in facilitating East-West cultural and artistic exchanges, please refer to Chinese Christian Texts Database (CCT-Database, https://www.arts.kuleuven.be/sinologie/english/cct) with special attention to Category: 12.03. Arts, crafts and language: Music.

[3] Xiqin Quyi was first printed as an appendix to Jiren Shipian 畸人十篇 (fols. 39–42), in Li Zhizhao 李之藻, ed., Tianxue chuhan 天學初函 (Taipei: Student Books, 1965). A later reprint of Jiren Shipian was edited by Wang Ruchun 汪汝淳, Chongke Jiren Shipian 重刻畸人十篇, Chinois 6831, Bibliothèque nationale de France, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k98181760. More editions of Xiqin Quyi can be found in the Chinese Christian Texts Database, http://heron-net.be/pa_cct/index.php/Detail/objects/3021.

[4] Tianyue Zhengyin Pu was originally preserved in manuscript form in a private collection in the Zikawei library of Shanghai (bibliotheca Zikawei 上海徐家匯藏書樓). In 1948, Rev. Fang Hao 方豪, a Catholic historian and Zheng Qian 鄭騫, a Chinese literary scholar and musicologist specializing in the Chinese musical sub-genre of qu 曲, collaborated in compiling and annotating the manuscript, and publishing it in 1950.

[5] For further discussions on these two musical works, please refer to the article by François Picard, “Music,” in Handbook of Christianity in China: Volume One: 635–1800, ed. Nicolas Standaert, vol. 15/1, Handbook of Oriental Studies (Leiden: Brill, 2001), 851–60. More discussion on Tianyue Zhengyin Pu , please refer to my article: Li-Xing Hong, “The Curious but Wondrous Sound of Chinese Sacred Music: On Tianyue Zhengyin Pu 天樂正音譜 by Wu Li 吳歷 (1632–1718),” in The Strange Sound: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Chinese Musicology in Bonn, October 3–4, 2014 (Bonn: Ostasien-Institut e.V., 2016), 61–82.

[6] Joseph-Marie Amiot, Musique sacrée, Recueil des principales prières mises en musique chinoise, Manuscrit, Collection Bréquigny 14, Bibliothèque nationale de France, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/ btv1b54100660g.

[7] More discussions on these rather unique phenomena of chanted prayers in China will follow in Part II of this article. For an analysis on Musique sacrée by Joseph-Marie Amiot, please refer to François Picard and Pierre Marsone, “Le cahier de musique sacrée du Père Amiot: Un recueil de prières chantées en chinois du XVIIIe siècle,” in Sanjiao wenxian: Matériaux pour l’étude de la religion chinoise 3 (1999): 13–72.

[8] The list is based upon the following publication catalogues: Catalogus librorum lingua sinica scriptorum qui prostant in Orphanotrophio T’ou-sè-wè. Zi-ka-wei, Chang-hai, 1904, 1909, 1917, 1923, 1934. Catalogue des livres imprimés à HO-KIEN-FOU (Sienhsien) 河間府獻縣天主堂, 1910, 1920, 1922, 1924, 1927, 1930, 1932, 1934; Robert Streit, Bibliotheca Missiorum, vols. 12, 13, 14 (1–3), continued by Johannes Dindinger, Johannes Rommerskirchen, Josef Metzler, and Nikolaus Kowalsky (eds.). The catalogues list most items by their Chinese titles and provide foreign language titles (including French and Latin) for some of them. The texts in the parenthesis indicate the titles in foreign languages as they appear on the publication catalogues. Those without titles in foreign languages are given transliterated titles and its literal translation in the bracket.

[9] Please refer to Part II of this article for the three types of sacred music.

[10] Archives de la Province de France de la Compagnie de Jésus (Vanves).

[11] The des Fontaines Jesuit Collection is a rich assemblage of books composed of publications used for the education and formation of French Jesuits, previously kept in the Jesuit Library of Chantilly.

[12] See Wang Lianming, “Church, a ‘Sacred Event’ and the Visual Perspective of an ‘Etic Viewer’: An 18th century Western-Style Chinese Painting held in the Bibliothèque nationale de France,” in Face to Face: The transcendence of the arts in China and beyond (Historical Perspectives), ed. Rui Oliveira Lopes (Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Lisbon, 2014), 371–99. Please also refer to Liu Qinghua, “Textual Research on ‘The Scenic Illusion Painting of the Feast of the Sacred Heart in Beitang’ in National Library of France,” in Chinese Art Quarterly 6, no. 2 (June 2019): 1–35. The digital file of the picture can be retrieved from the following website: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b541001700/.

[13] From the catalogue of the North Church in Beijing and that of Zikawei, missionaries who arrived in China during the late Ming Dynasty and early Qing Dynasty shipped volumes of Latin liturgical books, such as Missale Romanum, Rituale Romanum, with many of them containing music scores in four-line staves.

[14] Published in late 1870s, Chants sacrés à l’usage des missions opted to present the music on a five-line staff which became a convention that continued in later editions printed in the region. Cantus Sacri started with the use of four-line staff and square notation, but in later editions converted to a five-line staff.

[15] For example, in 1857, on the Assumption of Mary one of the four major feast days for the Catholic church, the Mass was celebrated solemnly with the grand inauguration of the bamboo organ at St. Francis Xavier Church in Dongjiadu 董家渡. Fr. Ravary described in detail the formation of his schola, as well as the liturgical music they sang during the Mass. Lettre du Père Ravary au Père Basuiau, Zikawei, à 30 août 1857, Archives jésuites (Vanves), Fch Dossier personnel.

[16] Dumont published Cinq messes en plain-chant, composées et dédiés au Révérend Père de La Mercy, du Couvent de Paris in 1669. Messe royale here refers to the setting “du premier ton” in this collection, thus it is a “neo-gregorian” setting of the seventeenth century.

[17] Difficulties for the Chinese people in learning Latin are well-documented. Please refer to Françoise Waquet, Le latin ou l’empire d’un signe (Paris: Albin Michel, 1998), 70–71.

[18] Belgian Jesuit composer, Louis Lambillotte is one of the strongest advocates for Gregorian chant in the nineteenth century, and he inspired Dom Pothier and others at Solesmes to pave the way for the restoration of Gregorian chant. See Michel Villedieu, “Un bicentenaire oublié : le Père Lambillotte,” Musica et Memoria 68 (December 1997): 21.

[19] A Chinese prayer book was first translated and compiled in 1603 in response to the need of Catholics who wanted to pray in their native language. Italian missionary, Nicolas Longobardi (1559–1654), was the key person who made the project possible. The editio princeps of Tianzhu Shengjiao Nianjing Zongdu (天主聖教念經總牘) in two volumes was first published in 1628. For the historic development of Chinese prayer books, please refer to Paul Brunner, L’euchologe de la mission de Chine editio princeps 1628 et dével oppements jusqu’à nos jours, Missionswissenschaftliche Abhandlungen und Texte Etudes et Documents Missionnaires Mission Studies and Documents 28 (Münster Westfalen: Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1964). Please refer to pp. 156–58 for the discussion of the chanting of the prayers by the Chinese faithful.

[20] “Ils chantaient à deux chœurs avec une dévotion qui me faisait souvent souhaiter d’avoir pour témoins de leur piété les chrétiens d’Europe. Ils ne savent ni le plain-chant ni la musique comme nous ; mais il se sont fait des airs qui n’ont rien de choquant et qui me paraissent même beaucoup plus supportables que ceux dont on use en plusieurs communauté de l’Europe.” Louis le Comte, Nouveaux mémoires sur l’état présent de la Chine (1687–92), II, 277.

[21] Niccolò Longobardo, AL Vice-Province 1613, Nanxiong, 1 August 1614, ARSI Jap-Sin 113: 360r/v, quoted in Liam Mathew Brockey, Journey to the East: The Jesuit Mission to China, 1579–1724 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 370–71.

[22] Albert Wetterwald, “Le chant des prières : lettre à un musicien,” Chine Ceylan Madagascar (September 1903): 22–28.

[23] “5 tons de l’Ave Maria,” Archives jésuites (Vanves), Fch 390 “Chants sacrés.” These transcriptions could have been made by two Jesuits, Jean Loriquet and François Ravary. Please refer to Antoine Dechevrens, S.J., “Études sur le système musical chinois,” Sammelbände der Internationalen Musikgesellshaft 2, no. 4 (1901): 485–551 at 536.

[24] “Music” (musique) and “symphony” (symphonie) here are French idiomatic expressions to indicate a poly- phonic choir and an instrumental ensemble.

[25] “…à quatre heures se dit la première grand’messe, avec musique et symphonie. Il y a un motet à l’exposition du très saint Sacrement ; la symphonie qui est sous la tente remplit les intervalles des messes ; celle qui est dans la chapelle a ses temps marqués dans chaque messe.” Please refer to Lettre du révérend père Cibot à Monsieur –– , à Pékin, le 11 juin 17––, in Lettres édifiantes et curieuses écrites des missions étrangères. Mémoire de la Chine, vol. 13 (Lyon, 1819), 376–78.

[26] “Ce sont les prières que nos Neophytes chantent pendant l’office, les jours de grande solemnité [sic],” Musique sacrée, 78.

[27] For example, Fr. Ravary describes in a letter that “The students start gradually and we come back singing with several voices or rather they sing a Chinese hymn (Les élèves se lancent peu à peu et nous rentrons en chantant à plusieurs voix ou plutôt ils chantent un cantique chinois).” See Lettre du Père Ravary au Père Basuiau, Zikawei, à 22 août 1856, Archives jésuites (Vanves), Fch Dossier personnel.

[28] More about these “imported” French songs, including their background and examples, please refer to Li-Xing Hong, “The French imprint on Chinese Catholic hymnals: The Case of the Cantiques chinois,” I.A.H. Bulletin 46, no. 2 (2019): 88–102.

[29] Alexandre Fleury, Recueil de cantiques et de chants latins, 5th edition, (Paris: Librairie Ch. Poussuelgue, 1911), 444.

[30] Fr. François Estève (1807–48) wrote in 1846: “We can well say that here divine worship is reduced to its simplest expression: there are not many differences between the days of great feast and the simple ferial days; we have no music, organ, singers, or lectern (On peut bien dire qu’ici le culte divin est réduit à sa plus simple expression : il n’y a pas beaucoup de différences entre les jours de grande fête et les jours de simple férie ; nous n’avons ni musique, ni orgue, ni chantres, ni lutrin).” Le P. Estève au R. P. Provincial à Paris, Chang-hai, 1er Juin 1846, in Lettres de nouvelles missions de la Chine, vol. 1 (1841–46), 346–47.

[31] Nicolas Broullion, S.J., Mémoire sur l’état actuel de la mission du Kiang-nan: 1842–1885 (Paris: Julien, Lanier et Cie, 1855), 67.

[32] See Paul Brunner, “La messe chinoise du P. Hinderer,” Neue Zeitschrift für Missionswissenschaft 15 (1959): 271–84; Raphaël Gaudissart, “La messe chinoise du P. Hinderer, S.J., (1668–1744),” Chine Ceylan Mad- agascar 114 (1936): 9–12; Ad Dudink, “The Holy Mass in Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century China: Introduction to and Annotated Translation of Yu Misa Gongcheng (1721), Manual for Attending Mass,” in A lifelong dedication to the China mission: essays presented in honor of Father Jeroom Heyndrickx, CICM, on the occasion of his 75th birthday and the 25th anniversary of the F. Verbiest Institute K.U. Leuven (Leuven: Ferdinand Verbiest Institute, 2007), 207–326.

[33] “Ce doit être un concert bien agréable au Ciel que ces milliers de voix qui, dès le matin, devançant même le chant des oiseaux, s’élèvent de tous côtés de cette terre infidèle, pour louer le Seigneur et le remercier de ses bienfaits.” Le P. Pierre Fournier à son frère, Tson-min, le 8 octobre 1854, in Lettres des nouvelles missions de la Chine, vol. 3 (1852–60), 131–32.

- Title:Sketching the Historical Soundscape of Sacred Music in China through Jesuit Sources

- Author: Li-Xing Hong

Article Type: Research Article - DOI: 10.51238/ISJS.2019.14

Language: English - Pages: 1–16

- Keywords:

- Volume: 1

- Issue: 1, special issue

- In: Engaging Sources: The Tradition and Future of Collecting History in the Society of Jesus

- Editors: Cristiano Casalini

; Emanuele Colombo

; Emanuele Colombo  ; and Seth Meehan

; and Seth Meehan

- In: International Symposia on Jesuit Studies

- Publication Date: 22 August 2023

Last Updated: 22 August 2023 - Publisher: Institute of Jesuit Sources

- E-ISSN: 2766-0644

- ISBN: 978-1-947617-09

APA

Hong, L.-X. (2023). Sketching the historical soundscape of sacred music in China through Jesuit sources. In C. Casalini, E. Colombo, & S. Meehan (Eds.), Engaging sources: The tradition and future of collecting history in the Society of Jesus (Proceedings of the symposium held at Boston, June 11–13, 2019) [Special issue]. International Symposia on Jesuit Studies, 1(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2019.14

CMOS

Hong, Li-Xing. “Sketching the Historical Soundscape of Sacred Music in China through Jesuit Sources.” In “Engaging Sources: The Tradition and Future of Collecting History in the Society of Jesus (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Boston, June 11–13, 2019),” ed. Cristiano Casalini, Emanuele Colombo and Seth Meehan, special issue, International Symposia on Jesuit Studies 1, no. 1 (2023): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2019.14.

MLA

Hong, Li-Xing. “Sketching the Historical Soundscape of Sacred Music in China through Jesuit Sources.” Engaging Sources: The Tradition and Future of Collecting History in the Society of Jesus (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Boston, June 11–13, 2019), edited by Cristiano Casalini, Emanuele Colombo, and Seth Meehan, special issue of International Symposia on Jesuit Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2023, pp. 1–16. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2019.14.

Turabian

Hong, Li-Xing. “Sketching the Historical Soundscape of Sacred Music in China through Jesuit Sources.” In “Engaging Sources: The Tradition and Future of Collecting History in the Society of Jesus (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Boston, June 11–13, 2019),” ed. Cristiano Casalini, Emanuele Colombo, and Seth Meehan, special issue, International Symposia on Jesuit Studies 1, no. 1 (2023): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2019.14.

© Institute of Jesuit Sources, Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, All Rights Reserved