Introduction[1]

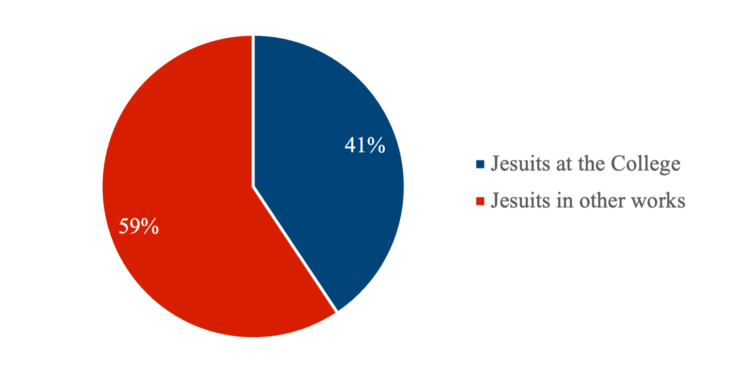

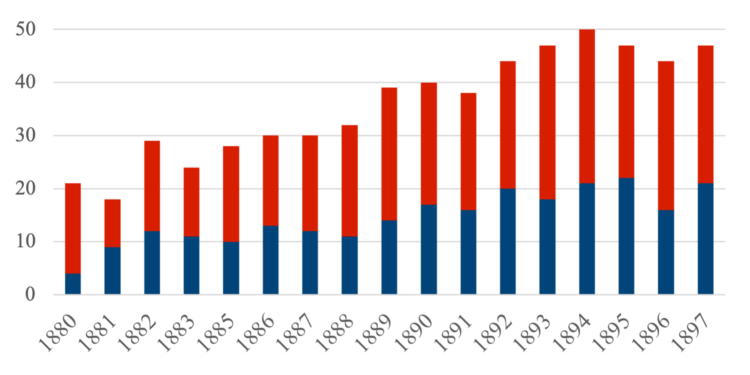

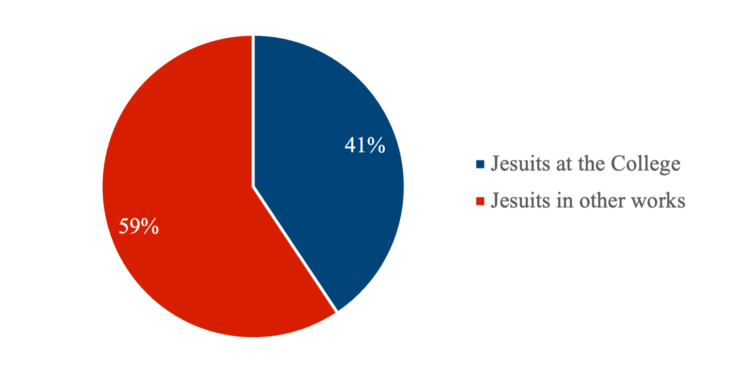

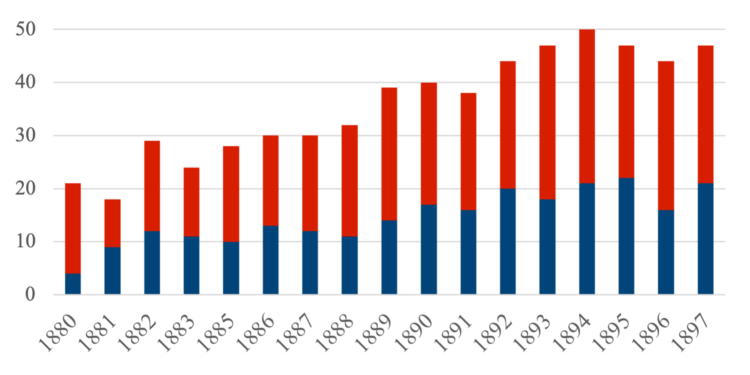

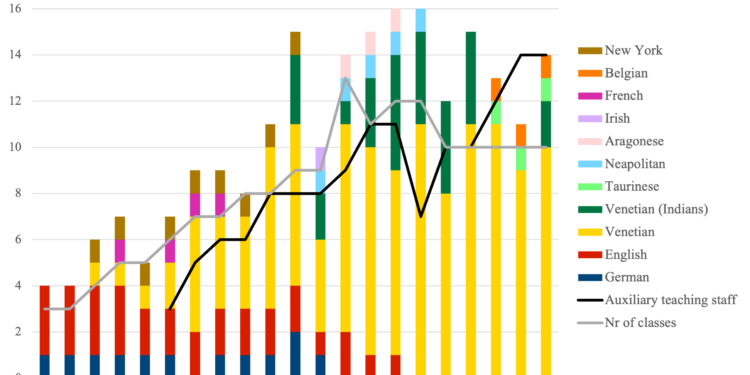

“If the College fails, then farewell mission!”[2] These words were reportedly often used when referring to Saint Aloysius College by Niccolò Pagani, S.J. (1835–95), the apostolic administrator, and after the institution of the Indian hierarchy in 1886, the first bishop of Mangalore. The Jesuit college was established in 1880 just over a year after the arrival in Mangalore of the Jesuits from the Venetian Province and in its first seventeen years it employed a vast portion, about 40%, of all the Jesuits recruited for the mission in Mangalore (Figures 1 and 2). Pagani’s expression hints at the key questions that will be explored in this paper. Firstly, why was the college so vital for the mission, as the speed of its foundation and the numbers of Jesuits employed also suggest? This paper will shed light on why the Society of Jesus was assigned to Mangalore in the first place, and it will show how the educational vocation of the order was decisive in this process. Secondly, what were the reasons that led Pagani to fear the closure of the college? What were the challenges? A detailed presentation of the life and activities of the college, as well of its Jesuit teachers will enable a clearer view. Furthermore, the Jesuits lived within the Indian context of the time: the British Raj. Further questions addressed here are: how did the Jesuit college integrate with the British educational network in India? And what were its distinctive features? Finally, the analysis will then turn to the connection between the mission (intended as an evangelizing effort) and the educational goal of the college.

The analysis will span about twenty years, starting with the assignment of the Mangalore mission to the Venetian Province of the Society of Jesus, and the arrival of the first Jesuits on December 13, 1878, then covering the preparation for the inauguration of the college and its activities in its first years, and concluding around 1896, although references to later developments will be made. The limit of 1896 has been chosen as it marked a major step in the history of the mission; after Pagani’s death in 1895 a new bishop, Abbondio Cavadini, S.J. (1846–1910), was appointed the following year. Cavadini had previously been the mission’s superior and was able to enact changes very quickly. The change in leadership is reflected in the preservation of some document series, namely, the Litterae Annuae and the Historiae Domus—distinctive documents of Jesuit administration—of the mission’s communities are available in the provincial archive only starting from 1895 or 1896. Furthermore, the years after 1896 also coincided with the arrival of a new rector (i.e. principal) and marked a time of significant expansion of the college, presenting different kinds of dynamics and issues from the founding years.

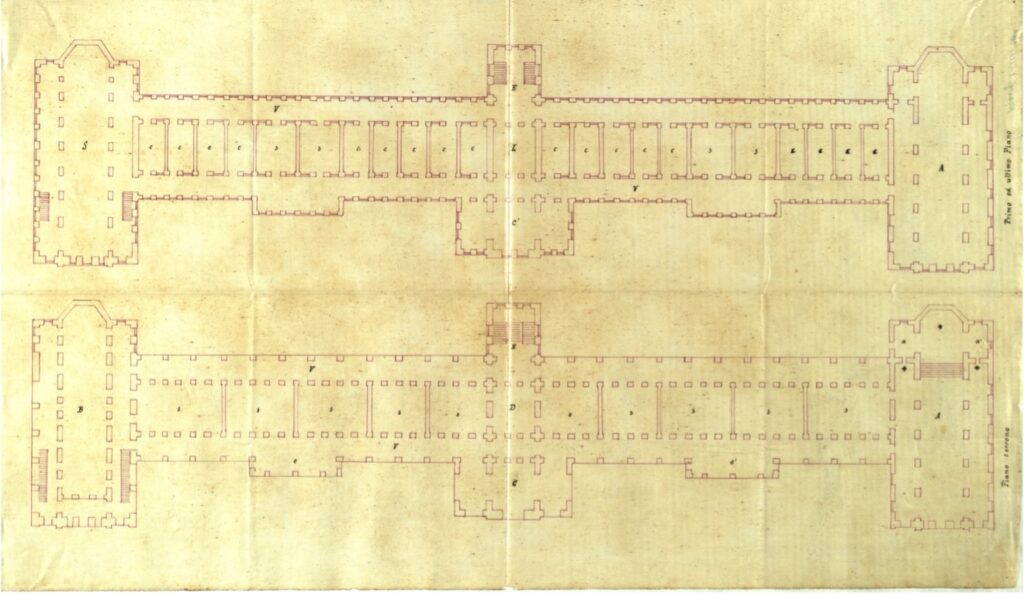

Figure 1. Subdivision of Jesuits in the Mangalore Mission. Data source: Catalogi Provinciae Venetae, 1880–97.

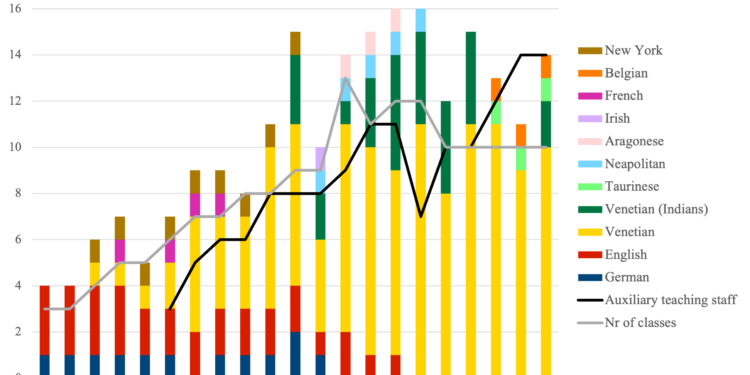

Figure 2. Distribution of Jesuits in the Mangalore Mission (1880–97), year by year. Data source: Catalogi Provinciae Venetae, 1880–97.

This analysis will be conducted by using primary (including archival) sources and secondary sources. Archival sources were consulted both at the central archive of the Society of Jesus (ARSI), and at the Historical Archives of the Euro-Mediterranean Province of the Jesuits (AEMSI) both based in Rome. These documents are chiefly administrative correspondence between Jesuits in Mangalore and their superiors based in Italy, but also reports, minutes of meetings, maps, and building plans. Primary sources also include the publication of some of these letters from India in journals internal to Jesuit provinces: the Lettere Edificanti of the Venetian Province and the English equivalent Letters and Notices. For the Jesuits’ personal details, roles, appointments, and missions, the printed Provincial Catalogs (i.e. annual directories) and the Catalogus Defunctorum 1814–1970 were extensively used.[3] Moreover, contemporary newspapers and publications, reports from other institutions in Mangalore at the time, and Jesuit internal legislation have been consulted and used. Finally, secondary literature addressing questions of Jesuit education and mission, as well as missionary education in colonial India have been utilized to sketch a bigger framework.

Mangalore Mission Assigned to the Venetian Jesuits

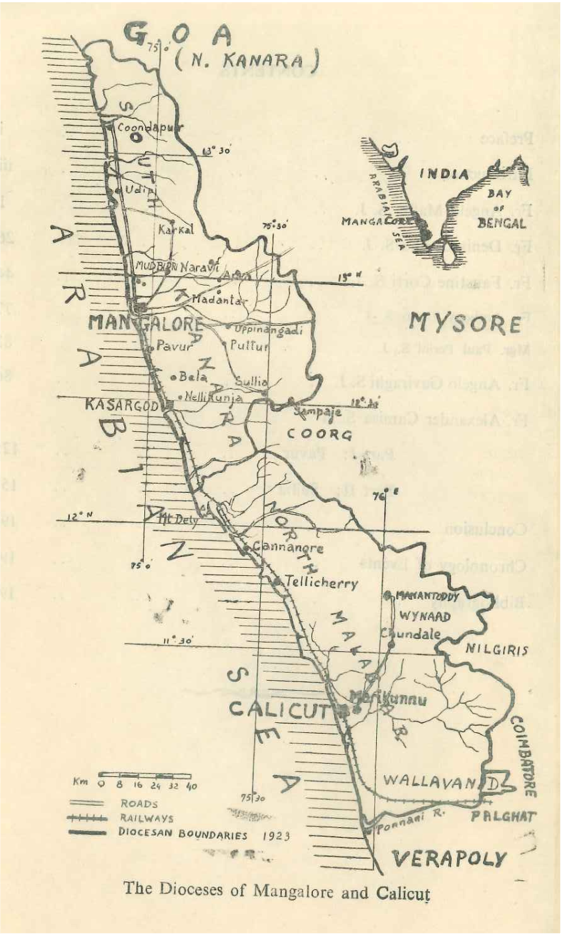

When the first Venetian Jesuits arrived in Mangalore on December 31, 1878, they were not expected to start a mission from the ground up but entered an urban and complex reality. At the time, Mangalore (Mangaluru, Karnataka) on the south-western coast of India, was a middle-sized city. It was located in the Madras Presidency, which comprised parts of what is now Andra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka, Odisha, and Telangana.[4] The Vicariate of Mangalore was erected in 1845 and was entrusted to the Carmelite order since its commencement; it bordered the Apostolic Vicariate of Verapoly in the south, and with the Archdiocese of Goa in the north. In Mangalore, according to the census of 1871, there were 30,000 inhabitants, of whom 10,000 were Catholics.[5] The Catholic community of Mangalore dated back to Portuguese colonization of India and the evangelization of Portuguese Franciscan friars in the sixteenth century, and were therefore Latin Christians (in contrast to the Mar Thoma Christians who derived from the Syrian tradition).[6] The Catholic community was diverse: there were Catholics in the outskirts of Mangalore, in the countryside, and, to the east of the city, in the mountains. These were usually outcasts working in coffee plantations in very poor conditions.[7] In the city, however, Christians were mainly from the aristocratic caste of the Brahmans. This did not necessarily mean they were wealthy: some were, as donations to the college show, but most of them were not. Hugh Ryan (1843–90), an Irish Jesuit who was among the first teachers at the school, noted that “many of the better and richer families among the Catholics had been ruined by speculation in coffee estates.”[8]

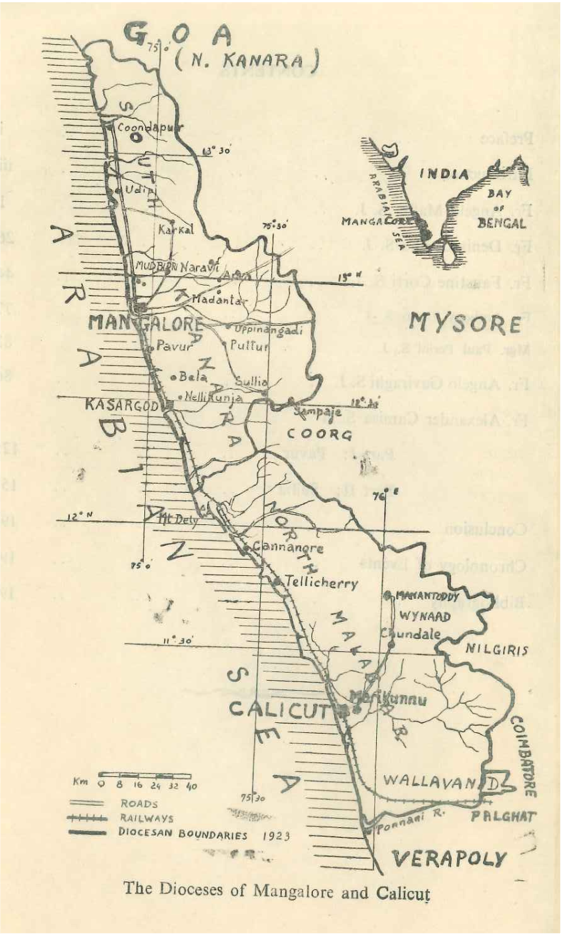

Figure 3. The diocesan boundaries of Mangalore. Source: Emanuele Banfi, Among the Outcasts (Rome, 1970).

For more than thirty years, the Carmelites engaged in a wide range of pastoral activities in parishes, parish schools, and the diocesan seminary, although the personnel of the mission were too few to respond to the spiritual needs of the Mangalorean Catholic community.[9] Starting from the late 1850s, representatives of Catholics in Mangalore repeatedly reported to ecclesiastical authorities the community’s dissatisfaction with the Carmelites’ work, and their lack of willingness to study the vernacular languages. What was alarming to Mangalorean Catholics, however, was that some Catholic students were attending Protestant institutions offering free schooling in English, vernacular languages, arts and sciences, and could have easily converted to Protestantism. In a letter dated June 29, 1873 addressed to Pope Pius IX (r. 1846–78) local Catholics explained that “trained to a monastic life they [the Carmelites] have shown no aptitude for the work of educating the people or for the work of conversion.”[10] In this letter they suggested to substitute the Carmelites with the Society of Jesus, which was in their view, the only religious order able to “show us the way of our spiritual and temporal progress.” The authors of the letter justified their insistence, originally made in 1868, by pointing to the efficiency of the Protestant missionary activities in the area, in contrast with the immobility of the Carmelites fathers.[11] Since the beginning, then, the Jesuit order’s function in Mangalore was imagined as playing a role in opposition to the Basel Mission’s activities, with both the spiritual and educational advancement of the community.

In fact, Catholics were not the only Christians in Mangalore: there was a community of Protestant missionaries and converts. The missionaries of the pietist Basel Mission (founded in Basel, Switzerland, in 1780 as Deutsche Christentumgesellschaft) had arrived in Mangalore in 1834.[12] The Indian South-Western mission of this Swiss missionary society was divided into four districts: one of them, the Canara-Coorg district, roughly covered the area of Mangalore and its surroundings. The evangelizing strategy of the Basel Mission comprised, along with the establishment of factories for poor converts,[13] the foundation of schools aiming at the conversion of “heathens” as well as the training of new converts to become themselves teachers and catechists, and therefore missionaries.[14] These schools were in Mangalore and across the district of Canara-Coorg, educating 1,078 students in 1879, a number roughly comparable to the number of students in Catholic institutions.[15]

Why did Catholics in Mangalore make explicit requests for the Jesuits? In contrast to other areas, such as the Pondicherry mission,[16] which was founded by the Jesuit Roberto de Nobili (1577–1656) in 1608, Jesuits had never been in Mangalore before. However, in 1833, a small group of Irish and English Jesuits arrived in Calcutta, West Bengal, soon after the order’s restoration in 1814. Belgian Jesuits landed in Bombay in 1854 starting the Bombay-Poona mission and were successfully running St. Xavier College since 1869.[17] Mangaloreans met the Jesuits through their college in Bombay. In fact, since the mid-nineteenth century, Mangaloreans started to migrate to Bombay for mainly two reasons. It was the more convenient choice for wealthy Catholics who wanted to receive a higher education in a Catholic institution, and, more importantly, many migrated to Bombay for job opportunities. Since the arrival of the British East India Company in India, Bombay had developed into a major hub for commercial exchanges between India and Britain. This circumstance contributed to the industrial and economic growth of the city, both pull-factors for migrations.[18] The exchanges between Mangalore and Bombay were significant, and Mangalorean Catholics came to envision an institution like St. Xavier College of Bombay for their own city and therefore started to request the Jesuits.

The expressions of interest by local churches for the Jesuits were not rare after the restoration of the order.[19] However, both Propaganda Fide, the Vatican institution founded in 1622 to oversee the missionary activities of the Catholic Church globally, and the Jesuit order itself were prudent in considering every request. The struggles and shortcomings of the Carmelites were known, and Propaganda soon tried to find a replacement for the friars. Archival material reveals that Propaganda at least as early as 1875 was actively pursuing the idea of sending Jesuits to Mangalore. The Prefect of Propaganda explained in a letter to the Superior General the reasons of his office’s decision:

[Propaganda]has laid her eye upon this Society [of Jesus], that due to its nearby and thriving institutes of Calcutta and Bombay promises to fully meet its [Propaganda’s] expectations both in spiritual matters and especially in the education of the youth.[20]

Propaganda embraced the local community’s wishes and intended to repeat the successful establishment of Jesuit colleges in the Indian subcontinent. The challenge Propaganda had to face, however, was to find via the Superior General, a Jesuit province that was both available and able to fulfil this mission. For some years contacts were made with different provinces,[21] but in 1877, when Propaganda reiterated its invitation to the Jesuits to take over the mission of Mangalore, on December 4, 1877, the Venetian province finally declared its readiness to assume the leadership of the Vicariate and its mission.[22]

At the time of the acceptance, however, the Venetian province had had very little missionary experience. The province was established in 1846 and had increased from its initial 216 Jesuits to 241 members in 1878, distributed in fourteen communities mainly across present-day northern Italy and one small mission (eight Jesuits) in Illyria and Dalmatia, based at the college in Ragusa (Dubrovnik, Croatia). Communities were spread across northern Italy and the southern part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Furthermore, a considerable number of Jesuits (fourteen) was running a pontifical college in Shkodër, Albania. Although the Venetian Province had no significant experience in missionary activity, other than in Dalmatia, it had acquired a relevant educational expertise. The province was running three colleges in Shkodër, Ragusa, and Cremona, as well as three diocesan seminaries in Ragusa, Cremona, and Zadra.[23] It is worth noting that the Jesuit presence in Albania, based in Shkodër, aimed—through its college, the diocesan seminary, and its “flying missions”—to support the local Catholic population, a minority among Muslims and Orthodox Christians. In fact, the mission to Albania closely resembled in its aim what was about to become the mission in Mangalore.[24]

The news of the substitution of the Carmelites with the Jesuits quickly reached Mangalore, and, as predictable, Propaganda’s decision was not welcomed by all. In a letter addressed to the Jesuit Superior General dated February 11, 1879, Augustine de Mourier (dates uncertain), a French missionary in Verapoly (Kochi) and most likely a Carmelite himself, fervently protested against this decision, arguing that for years the Carmelites had been successfully running the mission developing a good network of schools in collaboration with the Brothers of the Christian Schools and the sisters of the Apostolic Carmel,[25] supported by government funds. Fr. de Mourier insisted that the alleged need for a higher education institution able to award BA degrees had emerged only among the elite of Catholic families, who were educated in Protestant and government schools, desiring a career in the government administration for their boys. In other words, the request for a “special college” in Mangalore was formulated by few in the community; it would be an institution of which “the rest of the population has no need.”[26]

The Mission’s Beginning

The request for a Catholic college in Mangalore was however more popular than de Mourier had assessed. In fact, at the arrival of the Jesuits in 1878, hopes for a new Jesuit college in the city grew and the requests and pressures on the Jesuit missionaries became more insistent. However, both the missionaries in Mangalore and the Superior General in Italy were aware that the foundation of a college would require time, adequate teaching staff, and buildings, and thus many resources. In his address to the local clergy, the newly appointed Apostolic Vicar of Mangalore, Pagani foresaw the establishment of the college within the following twenty years.[27] The Jesuits however appreciated the urgency, especially due to the Protestant activities that were perceived as endangering the survival of the Catholic community. The anti-Protestant character of the college’s project, that emerged already from the community’s letters, was adopted also by the General, who, in a letter to Pagani, believed that the college was instrumental in “defending and safeguarding the Catholic cause against the efforts of German Protestants.”[28] Thus, the procurator (i.e. the bursar) of the mission, Angelo Mutti, S.J. (1844–86), immediately started to prepare the opening of the new Catholic college.

While these preparations were still under way, the Jesuits did not procrastinate the commencement of their educational mission in Mangalore. From the first weeks of their presence in Mangalore they pursued this mission in four ways.

The first achievement of the Venetian Jesuits was the reestablishment of St. Joseph’s, the local seminary, in the neighborhood of Jeppoo. By doing this, the missionaries meant to respond to the Propaganda’s instruction, Neminem Profecto of 1845. This instruction gave new strength and relevance to a widely ignored one of Propaganda dating back to 1659 that encouraged the establishment of local Churches especially through the training of local priests.[29] The theme of clergy formation gained new momentum in the 1840s due to the Synod of Pondicherry (1844), which, precisely due to the necessities of the Indian context, foregrounded the formation of the local clergy considering it “a necessary means for the propagation of the Christian religion,” as the instruction in the following year synthesized.[30]

Secondly, the seminary also responded to the moral and spiritual crisis the Jesuits observed in the local clergy, which in 1879 counted 29 priests under the jurisdiction of the Apostolic Vicar.[31] Scandalized by some attitudes and the poor reputation of the Mangalorean clergy among the local community, an alarmed Mutti wrote to his Provincial in Italy in March 1879 that “they are not more concerned with the conversion of the gentiles than in the conversion of the moon’s inhabitants.”[32] Thus the formation of the local clergy, as Neminem Profecto suggested, became a priority, and was not merely seen as a means by which the Catholic communities could be strengthened, but also a way to prepare future missionaries. With the knowledge of the local languages and culture, local priests and religious were seen as more likely to be successful missionaries.

A second way in which the Jesuits translated into practice their educational mission, was by engaging with the pre-existing Catholic educational network, that is by becoming directors of parish and convent schools.[33] Thanks to other religious congregations that preceded the Jesuits’ arrival—the Discalced Carmelite friars, Sisters of the Apostolic Carmel, and the Brothers of the Christian Doctrine—there were fourteen Catholic schools across Mangalore and the vicariate, serving over 1,000 pupils, both boys (723) and girls.[34] Teachers were not only members of religious congregations, but also local lay Catholics; for instance, in Tellicherry there were three male and one female teachers.[35] All these, either parish or convent schools, were elementary schools. The Carmelite nuns had three schools within the Vicariate, specifically dedicated to girls, while the Brothers of the Christian Doctrine oversaw two elementary schools. The other nine schools were entrusted to twelve lay teachers hired directly by the Vicariate of Mangalore.[36]

If education is taken in its extended meaning, the third dimension of the Jesuits’ work was the spiritual formation of the Catholic community. This pastoral outreach was oriented towards both the adult and the young members of the community. Following their foundational documents, including the Constitutions of the order, the Jesuits started in March 1879 to preach the Spiritual Exercises to Catholic men of the city, under the general name of conferenze (conferences), which were held in English and had a considerable following.[37] Catholic youth, who attended the non-Catholic college of Mangalore, were instead encouraged to participate in the activities of a Marian Congregation,[38] which were specifically established to serve their spiritual needs. These activities included catechism provided by Fr. Angelo Maffei, S.J. (1844–99), in Konkani, one of the local languages, since August 1879.[39] Nevertheless, the Jesuits agreed that the only efficient way to “tear the [Catholic] youth entirely away from the Protestants’ and pagans’ hands” was the establishment of the Jesuit college.[40] In fact, while those who could afford to move to Bombay could access college-level Catholic education, before 1880 in Mangalore there was only one institution where high school classes were taught, what the Jesuits called the “pagan” government college. It had been established by local authorities and was run predominantly by local teachers, who were not necessarily Christian.[41] Nevertheless, a considerable number of Catholics attended this college. There were about a hundred students who joined the Marian Congregation[42] and later Lutheran sources reported that the opening of St. Aloysius “deprived [the government college] of a considerable contingent of Roman Catholic boys.”[43]

The fourth activity the Jesuits initiated in their first months was the foundation of a Catholic library. Before their arrival, the “cultural monopoly” in Mangalore was held by the Basel Mission that successfully operated both a library and a publishing house. This situation created a certain unease among the Jesuits, who feared that with both the library and the publishing house Protestants facilitated the spread of “errors” in the Catholic community as well as conversions. The establishment of a Catholic library thus became a priority for the new missionaries, and fundraising started as early as August 1879. The library was set to be inaugurated in Kodialbail, not far from where a few months later the building of Saint Aloysius College began. As Pagani explained to the Assistant of the General in a letter dated August 17, 1879, the foundation of a new library would “prevent Catholics from going to the Protestant library.” He even prohibited Catholics to become members of the Protestant library, “and everyone has faithfully obeyed.”[44] Books for the library were mostly bought from England[45] using the regular contributions from Propaganda for the mission, highlighting the priority Jesuits gave to this activity,[46] and by 1882 the library had accumulated a collection of 2,000 books.[47]

Fundraising

Despite Pagani’s vague promise to open a college in the next twenty years, work on establishing the new college started very soon. The community’s commitment to the cause of the college was confirmed by the donation of a significant land property in Kodialbail, one of the best[48] neighborhoods of the town,[49] and a committee of Jesuits and local laymen was established for the construction of the college. The first goal of the committee was to fundraise. Four main sources of funding were identified. The first source was the local Catholic community, who participated both through donations and contributions by wealthier members, and through a voluntary taxation based on each family’s annual income.[50] Secondly, a fundraising campaign was launched in Europe, especially in France where donations arrived from affluent aristocratic families.[51] The third funding source was the institutional Church in Europe, namely the Venetian provincial, together with other Jesuit institutions of the province,[52] the superior general, and Propaganda Fide. These funds were transferred over the years to the apostolic vicar, who had, however, to negotiate between the needs of the college and support for the local diocesan clergy, the churches across the vicariate and the feeding of a growing number of people at St. Joseph’s Asylum.[53] Finally, the fourth source was the British administration in India, both through the governor-general and the presidency of Madras, since often before they had generously contributed to the establishment of other missionary and Jesuit colleges across India.

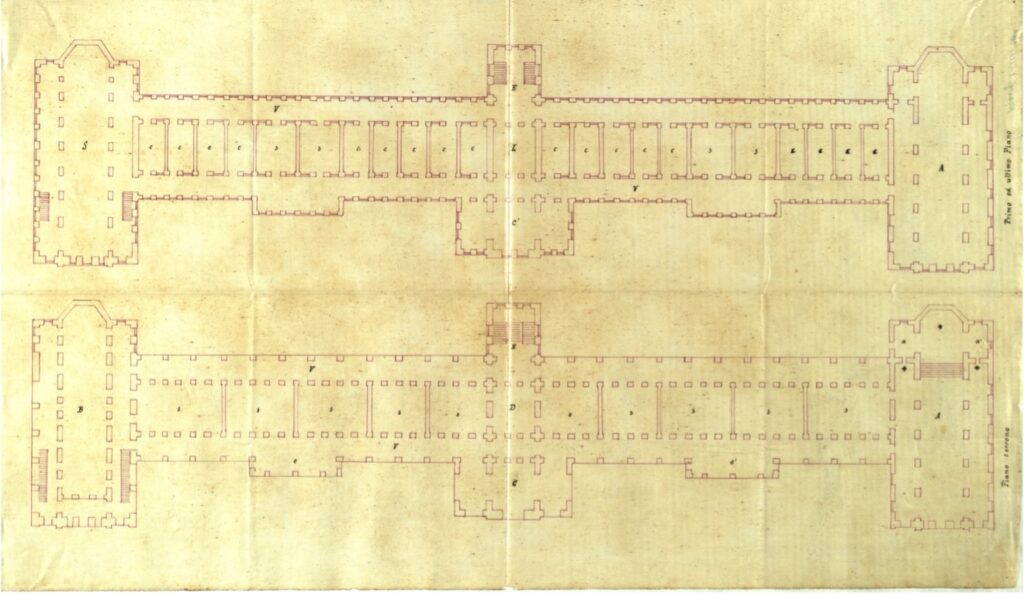

Nevertheless, in December 1880, one and a half years after the launch of the fundraising campaign, only 60,000 franks, out of the expected expenditure for the college’s construction of 200,000 franks, had been gathered.[54] The reasons were multiple, including the financial struggles of the Venetian Province, the limited resources of the superior general, and the disappointingly low contribution from British institutions.[55] Even though the financial status of the College improved over the years, receiving income from the students’ fees, government subsidies, ecclesiastical institutional contributions and offerings for masses, in 1893 all these sources were still insufficient for the ordinary maintenance of the college.[56] Thus, most of the first phase in the college’s construction was covered by loans, which in 1896 still needed to be repaid.[57] From the early stages of its existence, the college’s finances were a concern for the global leadership of the order. Throughout the first twenty years of the mission repeated appeals to attention in spending were made, and the Jesuits in Mangalore were often invited to refrain from the construction of more than what was strictly necessary and affordable at the beginning, and to wait for secure funds before progressing with the full construction of the new college.[58] Although construction was still under way, the state of the works allowed the Jesuit community to move into the new building towards the end of 1884,[59] while the students started to attend classes there at the beginning of the new academic year, in January 1885.[60] With the arrival of a new rector for the college in 1897, Egidio Fracchetti, S.J. (1856–1915), however, previous issues had—at least partially—been sorted. In fact, in 1898 Fracchetti had the opportunity to expand the buildings, with dorms, additional lecture rooms (necessary since the inauguration of the BA course in 1888)[61] and a hall for physical education.[62]

Figure 4. Plan of the new college (first and ground floor), submitted to the Superior General in 1880. Source: ARSI Karn. 1001, Missio Mangalorense, III, 28a.

Teaching Staff

The financial issues were often accompanied and intertwined with concerns about the staffing of the college, both before its inauguration and for many years afterwards. The uncertainties began when the designated teachers for the school were not among the first Jesuits who arrived from Italy in December 1878. Mutti, the mission’s procurator, who was also overseeing the fundraising activity, was asked to launch the Jesuit college by the forthcoming academic year, beginning in January 1880. Nevertheless, at the end of November 1879 the promised Jesuits had not yet arrived in Mangalore, creating a sense of profound uncertainty both in Mutti, as well as in the potential Catholic students who did not know whether to leave or renew their attendance in other schools.[63] Finally, in December 1880 the German Joseph Willy, S.J. (1824–97), who was appointed rector of the forthcoming college, arrived from Bombay, and at the beginning of January 1880 three men from the English Province (one of whom was Irish) arrived in Mangalore. Their arrival allowed Saint Aloysius College to open its doors to 150 boys on January 12, 1880, in a provisional building. Rented from a local Catholic, the location was too small to accommodate all the students; therefore, one of the classes was placed under a shed covered with coconut leaves[64] and once the monsoon season began, the spaces of the Catholic library were used.[65]

The provincial catalogs covering the college’s early years give a glimpse of the first Jesuits teaching at the college. It is striking that initially there were neither Venetian nor other Italian Jesuits involved in teaching or in managing the college, but one German and three English Jesuits. In fact, the Venetian presence increased slowly (Figure 5) over time; Venetian Jesuits took control only in 1886, after Joseph Willy had returned to Bombay and Cavadini, future bishop of Mangalore, became the new rector. The absence of Italian and especially Venetian Jesuits was due to two main factors. Firstly, most of the Venetian Jesuits at their arrival in India usually spoke only Italian (and Latin) and, exceptionally, German. Hence, they had almost no knowledge of English and needed time to learn the language so as to teach. Secondly, Italian Jesuits had less familiarity with the English education system,[66] and thus needed to be introduced by more expert Jesuits, in this case a German, who in turn had gained a significant experience in Bombay, and the three English Jesuits.

The Venetian Jesuits perceived the presence of English confreres as essential for the success of the newly established college. India being under the rule of the British Raj, the Jesuits reported that locals would have considered a college with English teachers to be of higher quality.[67] In order to compete with pre-existing institutions and attract students, even Catholics, the quality of the college needed to be high. Furthermore, especially at the beginning, Italians, probably due both to their ignorance of English and to the preference for English teachers, were victims of prejudice regarding their ability to teach subjects other than Latin.[68] Accordingly, as we shall see later in greater detail, the initial poor results of the Jesuit college’s students at examinations were attributed to the lack of English teachers.

Over the years, also thanks to the new building, the number of classes grew from three classes in January 1880, to ten classes in 1900, after reaching the highest point of thirteen classes in 1892 (Figure 5). This increase needed to be supported by an appropriate number of teachers. The college leadership’s priority was to recruit as many Jesuits as possible from across the global Society of Jesus, with a clear preference for Jesuits from the English-speaking world, especially English, but also Irish and Northern American. This task became a particularly complex matter, causing regular distress in the college’s leadership and uncertainties about Saint Aloysius’ future. The correspondence between Mangalore and both the provincial and the global leadership of the order reveals how the shortage of Jesuit teachers remained a chronic problem of the college, at least in its first decades of existence.[69] To the college’s repeated requests for more Jesuits the superiors in Italy often replied by admitting their inability to send more missionaries.[70] A combination of reasons as well as a global view of the Society of Jesus might be able to explain this situation.

Figure 5. Provincial provenance of Jesuit teachers at Saint Aloysius College (1880–1900); number of lay teachers and of classes.

The first cause was the temporary position of individual Jesuits in Mangalore. Thanks to modern means of transportation, moving between continents was easier, safer, and faster. Thus, in contrast to Jesuit missions in the early modern period, the appointment of a missionary to India was less and less a permanent assignment. In particular, men from provinces other than Venice remained in Mangalore just for a few years, before either returning to their home country or to another missionary posting; in other cases, Jesuits returned to Europe to retire or for health treatments. The increase of Mangalorean indigenous Jesuits, who were seen as a solution to the issue, due to their knowledge of both English and local languages, did not help to stabilize the situation. The college’s first years coincided with the early stages in their formation as Jesuits. Therefore, they taught at the college only during their regency[71] and after a few years moved outside of Mangalore for their theological formation. Thus, the struggle to find replacements was constant, almost yearly.

Secondly, the Venetian Province was involved with three other colleges and three seminaries in Europe and had to balance its forces among them. Besides, several Italian Jesuits in Mangalore were already busy running the diocesan seminary. Furthermore, as anticipated, Venetian Jesuits rarely knew English well enough to enable them to teach. Several attempts were made to include in their formation some time in England before going to India, to introduce them to the English language and the British system.[72] However, formation pathways that included England were never formally institutionalized, and to provide them with some basic knowledge of English, new Venetian missionaries normally spent a few months at the Jesuit college in Bombay, but were rarely able to immediately take over teaching roles at the college.[73]

The third reason for the staffing shortage was the inability of the English provincial to send more missionaries to other provinces. In fact, the shortage of English Jesuit teachers was not solely a Mangalorean problem. Even though the superior general regularly asked the English provincial for more missionaries for Mangalore, the answer was often negative. In fact, the English Province had to provide personnel for its own missions in Honduras, Guiana, and Jamaica.[74] Furthermore, the English Jesuits starting from the 1880s diverted some of their best scholars to the Oxford Mission, a project that eventually led to the opening of Campion Hall at the University of Oxford (1896).[75] Alternatives were offered from England, e.g. to send lay converts from Anglicanism who used to teach in English universities and were in search of a new job. However, this option was not considered suitable by the Jesuits in Mangalore.[76]

Only from 1885 did catalogs of the Venetian province list the number of “auxiliary” (or lay) teachers that collaborated with the Jesuits in the college. The reluctance was not linked to the lack of availability. As the overview of the Vicariate’s elementary school network has shown, there were lay Catholic teachers already employed by the Vicariate. Moreover, the Jesuits reported that many teachers in government elementary schools, especially in the outskirts of Mangalore, were Catholics. Probably financial constraints made it impossible to hire qualified lay teachers immediately. In contrast, Jesuit staff did not require a fixed salary. Especially at the beginning, the college was very much an “inter-provincial” work, meaning that Jesuits from several different provinces were called to contribute usually for shorter periods of time.[77] Furthermore, Jesuits themselves regardless of their origins were highly esteemed by the Mangaloreans as educators, as the letters written to Rome attest, and they were thus expecting Jesuits to teach in the new school.[78] Even though the number of lay teachers at Saint Aloysius increased over time, their salary was mostly covered by government contributions, and they never exceeded the number of Jesuit teachers.[79] Annual catalogs also show that, when lay masters joined the teaching staff, Jesuits mainly taught in higher classes, while lower classes were almost exclusively entrusted to non-Jesuit staff.[80]

Despite the integration of non-Jesuit staff, the challenge to appropriately equip the college with sufficient and high-level (i.e. English) faculty members continued, at the cost of the quality of teaching; this led some students to leave the Jesuit college and transfer to other ones.[81] One measure taken to fill the gaps were derogations to the order’s rules on its members’ formation, allowing Jesuits to return speedily to the college.[82] For instance, in 1887 the situation became so critical that the Venetian provincial wrote to the general asking him to intervene swiftly and concluded that if no other missionary was sent to Mangalore “we could start thinking about closing that [Saint Aloysius] college.”[83]

The biggest challenge for the college, however, was the staffing of the BA class, introduced in 1888, where teachers had to hold a degree to teach there. These were difficult to find, mostly because there were not many English graduates in Mangalore,[84] but also because their salary was seen as unaffordable due to the precarious financial status of the college. The choice of opening another class in these circumstances was highly ambitious, as was the constant development of the college. To provide adequate teaching staff, however, in 1888 the first lay professor for the university-level classes was hired, Mr. McDermott (dates uncertain), a European (probably either of Irish or English descent), the first alumnus of the Jesuit College in Bombay to pass the MA examination in 1873,[85] who agreed to receive a moderate salary. Moreover, Fr. Maffei, who had for many years prepared himself for the evangelizing mission among the non-Christians was called back from Cannanore and assigned to the newly established BA class.[86]

All the difficulties of the mission, especially those linked to the administration of the college—including staffing and financial resources—led the superior already in 1886 to consider entrusting the Mangalorean mission to some other province.[87] This request was initially not taken seriously, and was probably interpreted by the provincial as an exaggeration of the mission’s superior, but it was later addressed in one of the provincial consultations.[88] However, this suggestion was never accepted, nor were alternative Provinces identified.

The Indian Context

So far, the history of the college has been outlined with special attention to its internal evolution. However, the college needs to be situated within the wider framework of the British rule of India and its development of an education network. This broader lens has always been neglected in previous histories of the college, but it is fundamental when the structure, the pedagogy, and the everyday life of the college are explored.

A key moment in the establishment of Saint Aloysius College was its affiliation to the University of Madras, in 1882. With this decision, the Jesuit college entered a wider system of missionary education in India. The first Christian college in India awarding degrees outside of theology had been founded in 1818 in West Bengal, and since then, religious and, more precisely, missionary education had played a pivotal role in the development of a vast education network across British India. The Christian colleges were, however, not only educational institutions, but they had a distinctive missionary role: most of their students were non-Christian Indians, and Protestant missionaries hoped, through education, to promote conversions to Christianity among these, predominantly from higher castes, who would then bring other Indians to convert to Christianity. In a nutshell, colleges were not an end in themselves but were rather a means by which the Christian faith was to be spread among Indian peoples. Scholars like Joseph Bara highlight how the first half of the nineteenth century can be described as the “age of mission schools,” a time that coincided with the early colonial phase, and when “missionaries made best use of the government encouragement to develop a network of Western schools.”[89]

The Educational Dispatch, or Dispatch n. 49, dated July 19, 1854, sent by the president of the Board of Control of the British East India Company Sir Charles Wood (1800–1885), was “the British government’s landmark educational policy” for India.[90] It required the Indian authorities to create “a properly articulated scheme of education from the primary school to the university.” It ruled and influenced the development of the educational system on the Indian subcontinent for the whole second half of the nineteenth century, and beyond, characterizing this second section of the colonial presence in India as the “great period of the Christian colleges.”[91] The Dispatch sanctioned, among other things, the “promotion of Western knowledge and the system of grants-in-aid,”[92] a system by which private religious colleges would receive government funding if these were able to demonstrate with reports and in occasions of inspections that they could deliver an appropriate higher education instruction to their students. The framework created by the Dispatch was used in January 1857, when the Act of Incorporation was promulgated establishing three universities on the model of the University of London: the Universities of Calcutta, of Bombay and of Madras. These universities were, technically speaking, “affiliating universities,” which means that they were “examining bodies [. . .] and not teaching or residential institutions. These other functions should be left to the colleges.”[93] Colleges from across India, such as Saint Aloysius in 1882, could request to be affiliated colleges. The affiliation status allowed students at these colleges to sit university examinations at the end of their studies in their college of election, and, once these examinations were successfully passed, these universities awarded them a degree. On the one hand, this system allowed a centralized control of university degrees, on the other, the academic system so initiated could rely on a pre-existing and independently developing network of higher education, the missionary colleges, that maintained their governing bodies and “were not part of the university.”[94]

The policies put in place by the British government in the 1850s prepared a fertile soil on which colleges, especially Christian ones, thrived. In less than thirty years, between 1857 and 1882, the number of colleges affiliated to the three universities (Calcutta, Bombay and Madras) rose from 27 to 72, attracting more and more Indian (male) youth to higher education. For instance, in 1857 only 219 students sat matriculation examinations, while between 1881 and 1882, out of 7,429 candidates, 2,778 students passed the same examination.[95]

The 1870s were for Protestant missionaries a time of important development and rebirth of the educational system specifically in the city of Mangalore, after the English school of the city had closed in 1867. It is probably within this process of re-foundation of an educational network in Mangalore that the establishment of Saint Aloysius College can be located. In fact, the annual report of the Basel-missionaries for 1879 noted, not without concern, that in the forthcoming year not only was a Jesuit college to be opened, but also a municipality school.[96]

What has been presented here is just a sketch of the bigger movements that involved education in colonial India, and within which the founding and early development of Saint Aloysius College can be better understood. However, the Jesuits in Mangalore did not start Saint Aloysius College, aiming at enrolling non-Christian students in order to spread the Gospel among them (as was the case with other missionary—even Jesuit—colleges).[97] In fact, since there was already a Catholic community in Mangalore, which had even requested the Jesuit presence, their attention was more focused on that community rather than on the non-Christian population of the city.

Influence of the Indian Context on Saint Aloysius College

As the brief outline of the Indian context demonstrates, in contrast to the early modern period, after the Restoration of the Society of Jesus in 1814, the Jesuits had to adapt to a new and more structured reality. The rise of national states had led to the establishment of a set education system; Jesuit education, as conceived by the Ratio Studiorum of 1599, had to negotiate with these boundaries. To do so, the Jesuit superior general Jan Roothaan (1785–1853) instituted a commission whose aim was to update the first Ratio to the necessities of the nineteenth century. This renewed version was published in 1832 but, as some argue, the new Ratio “was rejected outright” by the provinces “for it was simply impossible to follow an educational plan that would be universally valid in the face of rapidly changing societies and diverse cultures.”[98] In 1893, addressing a group of Jesuits in formation, Superior General Luis Martin (1846–1906) deplored that subjects to be taught were prescribed across the Jesuit schools by local authorities, “but if we wanted to maintain the subjects as before, we can close our colleges.”[99] Saint Aloysius College was precisely in this situation. Unlike other missionary schools in India, that wanted to protect the high degree of autonomy they enjoyed before the Dispatch of 1854, the Jesuits in Mangalore succumbed quite soon “to the temptation to accept government money and the measure of control that inevitably went with it.”[100]

The affiliation caused the “complete dependence” of the Jesuit college on the University of Madras. For instance, when due to financial constraints decisions had to be taken in order to save money, the college’s leadership was not allowed to reduce classes or hours of teaching, since the schedule of the college “at this point is fixed, hour per hour, by the University of Madras.”[101] The main advantage of the college’s affiliation with the University of Madras was the ability of Saint Aloysius to award degrees. College degrees were essential for Indians to qualify for positions in the British administration, as lawyers or clerks, or as civil servants.[102] These positions were attractive for people from poor or agrarian families and were a way, maybe the only one viable, for social advancement. The degrees awarded at the Jesuit college aimed precisely at giving the opportunity to Mangalorean Catholics to access these job opportunities and so to improve their financial condition.[103]

Further, the unified examinations allowed the establishment of a common syllabus across the Presidency[104] and a standard measurement and ranking of the colleges’ quality. The results of the examinations were published yearly and were an occasion for the teaching staff of Saint Aloysius to have an overview and evaluation of the college’s performance in face of other institutions in Mangalore and beyond. In its first fifteen years, the academic results of the newly established Saint Aloysius College were largely unsatisfactory.[105] Concerns among the Jesuits grew, especially because the low success of the students in the state examinations were bad publicity for the school, which meant the loss of current and prospective students.[106] These deficiencies were regularly reported to Rome and to the Venetian provincial; it was explained that the reason was the lack of teachers, especially native English-speakers: thus, these reports were often also a strong request for help. It is hard to tell whether the gravity of the situation was fully appreciated by the order’s leadership as the superior generals remained always very hopeful and encouraging in their letters. Nevertheless, when in 1896 the college welcomed the governor of Madras and a report on the progress and state of the college was given, the situation described was finally more satisfactory, with a good rate of success at the BA examinations, making of Saint Aloysius allegedly one of the best colleges for its BA in the area.[107]

While on the one hand the affiliation system made it possible to award degrees and to have a standardized measurement of schools’ quality, on the other hand Jesuits had to adapt to the rules set by the university and the British government, even though it sometimes meant abandoning longstanding distinctive features of the Jesuit way of proceeding. The first custom the Jesuits in Mangalore abolished was the gratuity of Jesuit education. Even before Saint Aloysius’ formal affiliation, Jesuits required students to pay a monthly fee,[108] following the fee rates as set by the government on September 1, 1871.[109] It was not in the tradition of the Society of Jesus to request fees for its schools. Although the practice of free schooling was not abolished by the Ratio Studiorum of 1832, in January 1833, due to requests coming especially from the United States,[110] Superior General Roothaan issued a decree, Facultas Accipiendi Minervalia in Collegiis Americae, Angliae et Hiberniae, exempting Jesuit colleges in North America, England and Ireland from the rule.[111] The Jesuits in Mangalore therefore felt permitted to adapt to the local laws. The Jesuits understood the imposition of fees by British authorities as a way to avoid “the country to being drained of agriculturists,” if schooling were free. Nevertheless, the Jesuits noted, some poor families were able to support their boys’ education. Even though the law virtually prohibited free education, the Jesuits sought to avoid that boys whose families were unable to afford the fees were automatically excluded from the college. The Jesuit bishop frequently supported some students, both Christian and non-Christian, awarding unofficial scholarships.[112]

The Ratio Studiorum, even the 1832 edition, listed the courses to be taught in a Jesuit college. For instance, to the subjects prescribed in 1599, an additional one was added in the new edition: physics.[113] The other courses included in the theoretical framework of Jesuit education were grammar, rhetoric, philosophy, mathematics etc. However, at Saint Aloysius, the program and syllabus were set by the University of Madras. The curriculum included, depending on the school year group, arithmetic, mathematics, and geometry, history and geography, natural sciences (physiology), English and English literature, as well as three local languages, Canarese, Malayalam and Sanskrit. As the college expanded, especially in its higher classes, new subjects were introduced, such as ethnology, philology, political economy, and political sciences. Not only were the Jesuits constrained by rules set by the university regarding the subjects, but they were also not allowed to use textbooks of their choice but had to adopt those indicated by the university. This created, especially at the beginning a certain concern, as they considered these books a possible source of interference with the education of the Catholic youths: written by Protestant authors, these books were “necessarily” transmitting Protestant “errors” to their readers, even if only indirectly, especially when dealing with history.[114]

In Search of a Distinctive Jesuit Identity

How then did Saint Aloysius translate its Jesuit identity into the Mangalorean context? What was distinctively Jesuit in a school, where not all the teachers were Jesuits, where the program, syllabus, and textbooks were prescribed by a non-Catholic government and where not all the students were Catholics? Where was the Jesuit autonomy and way of proceeding in this? When addressing these questions in a speech to the scholastics (Jesuits in training) of Xanten in 1893, the superior general Martin pointed to the “forma et method docendi,” literally the shape and the method of teaching, that emerged, in his view, “in many little things.”[115] What were these “little things” at Saint Aloysius College?

Formal Teaching

The first distinctiveness can be found already in the choice of some of the courses taught. Missionary colleges, in addition to their fixed set of classes and courses, were allowed to add other classes otherwise not included in the government’s program. In the case of Saint Aloysius, these were Latin and catechism. These were not electives but were an integral part of the program the Jesuits offered. However, not every student was Catholic, and some were not even Christians. Thus, since the opening of the school in 1880 catechism, as well as attendance at religious services, was only optional for non-Catholic boys.[116] Nevertheless, at the beginning of 1897 a class in “general ethics” for non-Christian high-school students was introduced once a week, which they attended while Catholic students were doing catechism.[117]

The timetable of the college did not appear particularly unique. School began at 10 a.m. and lasted until 12:30 p.m.; in the afternoon classes resumed at 2:45 p.m. and ended at 5:15 p.m. Lessons lasted 50 minutes each, and there were three in the morning and three in the afternoon. While there might have been nothing particular about these schedules as such, it was their choice that had a distinctive “Jesuit” character. As the Ratio recommended, it was the superior provincial, in this case in Italy, who approved the schedule, and it was he that the Jesuits in Mangalore consulted to make any change. The rare need for schedule-changes reveals the ruling principle: the rhythms of Jesuit prayer and community life. In the break between morning and afternoon classes they were seeking to find enough time for their “examen of consciousness,”[118] lunch, and recreation.[119] On a similar note, other changes were introduced in 1897 to the structure of the academic year: the Christmas holidays were shortened, while the summer vacations (April and May, coinciding with the beginning of the monsoon season, and following the Ratio’s indication not to give more than two months of vacation)[120] were both extended, in order to avoid having classes in the hottest time of the year, and anticipated, to allow Jesuits to reach their vacation location before the monsoon inhibited the journey by boat.[121]

The archival sources so far analyzed do not seem to address pedagogical matters in great detail. It is thus hard to have a complete overview on whether there was a clear distinctiveness in the Jesuit “method,” as Martin suggested. However, what seems to emerge in one instance, is a debate between the German rector, Joseph Willy, and the other teachers at the school, on how to deal with the correction of students’ written exercises. In fact, the Ratio prescribed that “the written works of individual students should be corrected daily by the teachers.”[122] This might suggest that the Ratio was used as a guideline at least for pedagogical matters. To solve the issue in this individual instance, the general suggested to follow the practices in both English and Indian colleges, allowing therefore a certain degree of freedom to adapt to the circumstances of the college, with the possibility of reviewing them at a later stage.[123]

Extracurricular Activities

Parallel to more institutional features of the college, there were other activities students engaged with beyond the formal teaching time. Jesuits strongly believed that education was not only delivered through classes, but by a wide range of complementary activities by which their intellectual, human, and spiritual dimensions were able to grow and develop.

One of the distinctive features of Jesuit pedagogy was the use of theatre and choirs, performing on certain occasions during the academic year, such as the birthday of the rector, visits by distinguished visitors or the solemn distribution of prizes.[124] As some scholars have highlighted, while theatre was a constitutive part of Jesuit pedagogy in the early modern period, after the Restoration of 1814, the attitude of the Society of Jesus towards theatre as a pedagogical means had shifted and became more prudent, if not even restrictive.[125] This change of attitude is mirrored also in the early years of Saint Aloysius College. In a minute of a meeting between the general and an assistant on December 16, 1880, a minute which was later dispatched to India by the Venetian provincial, the decision was taken to forbid public dramatic performances in places where these were not already present, especially among girls. The fear of the order’s leadership was to encourage the opening of other public theatres in these cities.[126] Mangalore was precisely in this situation, but the same question was raised again in 1886, when the superior of the mission wrote to Rome to verify these guidelines. Apparently, some Jesuits had wanted to have the boys perform at the distribution of prizes of 1885. In that circumstance, the superior had learned too late about the 1880 decision, when the play was already prepared, and it was decided to perform it anyway without costumes and scenography. In his query, the mission’s superior wrote directly to the Vicar, expecting further instructions from the general.[127] No trace of further guidelines by the general for Mangalore have yet been found; however, other documents suggest that permission was granted for boys to perform theatre plays.[128]

This introduces us to the second distinctive Jesuit feature: the distribution of prizes. Following the indications of the Ratio of 1832, which maintained intact the tradition of the pre-1773 Society,[129] the Jesuits in Mangalore introduced the system of prize-giving. This usually occurred in the college hall at the end of the academic year, around mid-December.[130] The prizes were often monetary gifts or books (that were very expensive at the time) and these were sponsored usually by the bishop, wealthy Catholics or friends of the college. For instance, the head of a village just outside Mangalore, Dharmasthala, had offered a yearly contribution for a 90 rupees prize for the best BA student. The ceremony of prize distribution had a public character, and numerous guests were invited every year, particularly families of the boys of the college. For instance, in 1889, when there were 350 students, more than 300 guests attended the event.[131] The solemn celebration would start with a choir performance, followed by a drama. In these occasions also a “Madmen Choir” performed, usually between the acts of the drama. The distribution of prizes itself followed these performances.[132] Every year, different public figures of Mangalore and beyond were invited to preside at the ceremony and to award the prizes to the boys, such as the governor of Madras (1896), the local bishop, a banker (1897),[133] and a judge (1891).[134]

In addition, sports, games, and physical education were integral parts of the formation of the boys at Saint Aloysius. Apart from the regular physical education class, common to every school in the presidency,[135] several sports were practiced in the college. Usually, around 5 p.m., after the afternoon classes, “when the sun’s heat is decreasing, and when a fresh sea-breeze blows invariably,” between eighty and hundred boys used to play football in front of the college. Cricket was also frequently practiced, and the students’ team regularly participated in competition with other college teams. Moreover, behind the college there were courts for lawn tennis and badminton, where only First Arts and BA students were allowed to play. All these sports were practiced outdoors, and at times the Jesuits themselves also participated.[136] Since there was no covered gym before 1897, these activities were suspended during the monsoon season. Instead, students practiced stilt walking and pole jumping under the college’s porches. In the yearly report on education in the Presidency of Madras for 1888, the director of public instruction reportedly noted that “no important institution in this Presidency is without any provision made for physical education and the St. Aloysius College seems to form one of the eccentric exceptions to the general rule.”[137] In fact, the Jesuit college did not yet have a covered gym, particularly important during the monsoon season. However, an anonymous reader of the Madras Mail, who allegedly had “no connection” with Saint Aloysius College but nevertheless appeared to be well-informed about the college, listed some of the sporting activities practiced at the College before the construction of a gym.[138] The anonymous author also revealed that cricket was played at the college since 1882 and that at the “College Gymkhana” of 1885 the Saint Aloysius team even won against the government college.[139]

Games and sports were practiced in other contemporary schools too, as the report of the director of public education suggested, but within Jesuit schools they acquired a precise pedagogical purpose. When Fr. Fracchetti began his tenure as rector of the college in 1897, he gave a report to the superior general on the progress of Saint Aloysius and admitted that sports and games had not been valued enough in previous years and his aim was now to give them more prominence.[140] In fact, since the sixteenth century sports had always been part of Jesuit pedagogy, and were a “a prominent feature of Jesuit education throughout the early modern period.”[141] This prominence continued consistently also after the Restoration of 1814. In this line, in 1875 in France, two Jesuit teachers published a book based on research, consultations and their own experiences, Les jeux de collège, a collection of rules, remarks and suggestions for games for the students to play. New games, variations on known ones, clear rules and their enforcement by the Guardian (usually a Jesuit) “strengthened by the authority that God has entrusted to him” were essential to channel the boys’ “douce violence” in an ordered and moral way, maintaining their enthusiasm and avoiding that they may fall into “hand games, gangs, coteries, inactivity, in a word, disorder.”[142]

Devotional Life

As the Catholic community requested in its letters to Rome when it suggested to replace the Carmelites with the Jesuits, the College served also for the spiritual and religious formation of its students who were mostly Catholic. Together with the multifaceted education (intellectual, physical, and moral) offered by the Jesuits fathers they also concentrated on the devotional growth of their pupils. It was not confined to the catechism classes, as mentioned above, but the boys were also incorporated in a Marian Congregation. Similarly to what had been done with the Catholic students at the government college before the foundation of Saint Aloysius, the Superior general instructed the Jesuits to form another Marian Congregation in order “to promote piety and devotion” among the college’s students.[143] This was pursued in different ways. The center of the congregation’s activity was in the chapel of the college, which served almost exclusively the college community. The meticulous recording of the sacraments administered at the chapel can give a glimpse of the college’s religious and sacramental life. For instance, throughout 1896, 22,800 confessions were heard and 19,980 hosts consecrated. Confessions outnumbered consecrated hosts, indicating firstly that it was extremely common for students to go to confession before every Eucharist. Moreover, once the numbers of the sacraments are divided by the number of Catholic students for that year (400), the outcome is about 50, which is a bit less than the number of the weeks per year. It is possible to conclude that while mass was probably said every day (at least by the priests of the Jesuit community), students received holy communion once a week during term time, showing how the Jesuits’ pastoral work emphasized the importance of frequent communion.

The devotional life of the chapel was not limited to mass and liturgies, but included other forms of piety, such as the prayer of the rosary. Particularly during the month of October, traditionally associated with the rosary, boys were invited to contribute to the prayer by singing the rosary and the litanies.[144] Moreover, they participated as a congregation in solemn processions and services that involved the wider Catholic community of Mangalore. It is hard to disassociate the life of the college from the students’ Marian Congregation, whose activities included both devotional and recreative aspects. In fact, outside of term time, the fathers organized regular excursions with the students’ congregation reaching by boat a beach just outside Mangalore where they enjoyed games and time together.[145]

Among the tasks given to the Jesuits in Mangalore, the support and strengthening of the local church had been the priority. As already noted, Neminem Profecto (1845) considered the promotion of indigenous clergy as the chief means to do so. The intellectual and religious education offered at the college also contributed to this aim. The education of young Catholic boys also indirectly influenced the selection and formation of both local diocesan clergy and members of the Society of Jesus. Not infrequently, young men of Saint Aloysius after completing their studies joined the diocesan seminary to be trained and to become diocesan priests.[146] Similarly, others requested to join the Jesuit order. In 1882, the superior general had allowed the admission of indigenous candidates to the Society. For practical reasons, mostly linked to the need of personnel in the mission and to the limited financial sources that would impede them from travelling to Europe, a novitiate was instituted within the premises of the diocesan seminary, erecting de facto a second novitiate within the same Venetian province, together with the one in Europe. When giving permission to accept indigenous candidates the general had set a few additional conditions to the common practices of the Society. Firstly, they had preferably to be formed in the Jesuit school before their admission, hence the importance of the college. The general stressed the importance for the candidates to the Society to be of good moral and intellectual abilities; thus, a further requirement was that they had completed either First Arts or a BA degree.[147] Furthermore, although there was not a fixed rule, the general suggested that it was preferable to admit youths who were not of the lowest caste, but that would be respected in the larger civil society, and thus he discouraged the admission of pariahs to the novitiate.[148] The justification of the degree-requirement was that the local Jesuits would have thus been able to help as teachers of the college whenever necessary.[149] The requirement to exclude the pariahs from the Society needs to be understood within the wider context of social interactions between castes and the missiones inter paganos, i.e. the evangelizing mission among the non-Christians, as we shall see shortly.

Saint Aloysius and the non-Christian Population

So far, the Jesuits’ efforts aimed at the survival and the development of the college have been described. However, while the college and seminary were the foundational aspects of the mission, the reader must not think that they were the only pastoral works the Jesuits engaged with in Mangalore. Along more traditional apostolates, such as running parishes and parish schools or military chaplaincy, another significant work, whose legacy continues until today, was the asylum of St Joseph.[150] Furthermore, as mentioned, there was a Catholic library, and a Catholic publishing house was inaugurated soon after.[151]

What seems to be missing from this overview, and from the analysis of the yearly catalogs of the mission, was a Jesuit assigned to the traditional evangelizing mission inter paganos, i.e. among the non-Christians. In fact, conversion of non-Christians was not only secondary in the Mangalorese mission but was almost completely lacking.[152] Only one case was reported of an active mission among the non-Christian population, that by Angelo Maffei, S.J. (1844–99) in 1883. After joining the mission in 1880, Maffei had dedicated himself immediately to the study of local languages—Tulu, Canarese and Konkani[153]—preparing himself for the missionary work among the non-Christians, which he began in 1883. This experience, unique in the first 20 years of the Mangalorean mission, ceased in 1885, when his superior appointed Maffei to Cannanore to be a parish priest. As the Venetian Jesuits themselves proudly reported in the Lettere Edificanti, conversions occurred especially in the countryside and at the asylum. However, there was neither a dedicated team nor a plan to promote conversions. The converts were mostly poor people, from low castes or even outcasts, people who had nothing to lose. In the eyes of the Jesuits this trend, however, appeared to be counterproductive, as the Christian faith was growingly associated with low-caste people, and was thus less attractive to intellectually skilled high-caste Brahmans. In fact, conversions of Brahmans would have made the Christian faith more acceptable for other fellow Brahmans and people from every other caste. It was precisely to avoid the association between Christianity and the outcasts that these were excluded from admission to the Society.

The only frequent and institutional contact between the Jesuits and Brahmans, and thus the only potential occasion for conversions, was the college with its very few non-Christian students. However, the school, rather than being a starting point for missionary work among non-Catholics, served mainly as a point of reference for the Catholic community in Mangalore and the surrounding areas of the diocese. Furthermore, in the college there were almost no conversions. In fact, conversions were avoided as much as possible out of dread of the reaction of the Brahman community; Jesuits feared events like the disturbance which occurred at Madras Christian College in April 1888 when Brahmans fiercely demonstrated against the missionaries due to the conversion of one student.[154]

This situation contributed to the slowness of the spread of the Christianity in the area. The lack of visible progress of the Christian faith in India did not pass unnoticed by Propaganda Fide. The challenges encountered by the Jesuits were probably not fully appreciated by Propaganda, which repeatedly pressed the Jesuits in Mangalore to give more attention to the non-Christian population in the diocese and to push for conversions. This request was reiterated many times over the years but was never really answered. The main justification for not engaging was the lack of personnel. The Jesuits at the school, burdened with extra work due to the lack of teachers, were unable to contribute to this mission inter paganos.[155] Furthermore, in many letters the Jesuits in Mangalore were insisting that conversions were very hard to achieve, especially among the higher castes.[156] Conversions, however, were not completely absent from the Jesuits’ radars. The reestablishment of a diocesan seminary, aiming at the formation of a local clergy, had a precise missionary aim: a well-formed local clergy was potentially more efficient in evangelizing fellow Mangaloreans, due to their knowledge of the local culture, customs and especially languages.

The lack of progress of Christianity within Jesuit missions was a common thread across India, not only in Mangalore where there was a significant Catholic community already, but also in places such as Bombay, where the population was mostly non-Christian. It is not a coincidence, therefore, that the new instruction (or document) of Propaganda entitled De Gentium Conversione—published on March 19, 1893, was addressed to the bishops of India and indicated the conversion of the “gentiles” as a primary goal.[157] The importance of this instruction for the diocese of Mangalore was highlighted by a private letter from the apostolic delegate to India, Mgr. Zaleski, to Bishop Pagani, inviting the diocese to strive for the conversion of locals as the instruction suggested.[158] A study on the instruction and its effects is still lacking. Nevertheless, it seems that the actions it tried to promote were either missing or had failed. In the 1920s, a visitation of India by an official of Propaganda revealed that there were no significant improvements in the field, and especially the educational institutions were criticized as they absorbed significant resources, but “they [did] not have a missionary scope whatsoever.”[159] Moreover, the first Jesuit to slowly resume the evangelizing mission started by Maffei in 1883 was Faustino Corti, S.J. (1856–1926), in 1906, who encountered significant challenges.[160]

What then was the understanding of Venetian Jesuit missionaries in Mangalore of “mission”? While expressing their missionary ideals often with a traditional “militant” language, they did not understand the concept of mission merely as “conversion of non-Christians.” They combined it with other dimensions: firstly, with the social advancement of Catholics in Mangalore, and especially the boys at the college. When complaining about the complete dependence of Saint Aloysius on the University of Madras, due to the affiliation, Carlo Villavicencio, S.J. (1854–1925), one of the Jesuit teachers of the college insisted that they needed to endure in all these challenges for the sake of Christian community, to which they had promised the same quality of teaching as at the University of Madras “to free thus their children from perdition; and we have to keep the promise, if we do not want to ruin forever the career of so many youths.”[161]

In the Lettere Edificanti of 1889, a Jesuit from the College of Trichinopoli (Tamil Nadu) reflected on the role and importance of the Catholic colleges in India, even if they had not yet been successful in converting the Brahmans. The main argument was that by abandoning the field of education, they would have handed it over completely to the Protestants. Furthermore, they needed to keep the hope to succeed in the long term among the Brahmans, considered a highly intelligent and moral grouping. The Jesuits were fascinated by this caste: “It is impossible that ten million men can make two hundred million others believe that they are superior, if they were not indeed so.”[162] Thus, the Jesuit from Trichinopoly concluded that “the conversion of the Brahmans to our religion is highly desirable, since it would cause a large number of conversions among other castes,” and that education (and thus the colleges) was the only means by which the Catholic missionaries were able to achieve this goal.[163] The colleges were thus very important for the Catholics to remain and grow in prestige in the eyes of Brahmans. When giving an account of the population of Mangalore, the editor of the Lettere Edificanti of 1888 noted that more than half of the population in Mangalore was either non-Christian or Muslim, contributing to a “harmful” atmosphere, but “thanks to the religious and civil education, which they have of higher quality than the others, [the Catholics] are respected by everyone, and are admitted to all positions by the government.”[164] The Italian missionaries strongly believed that by maintaining the college, high-caste Indians viewed Jesuits not merely as outcastes, and that therefore, maintaining the colleges was a priority, the few conversions notwithstanding.[165]

Conclusions

The paper has offered a European and Jesuit perception of the genesis and the early years mission in Mangalore. A distinctive element of this mission, compared to others, was the chief focus of the Jesuit missionaries on fostering the Indian Catholic community, while the evangelizing mission to non-Catholics remained secondary, at least in the first years. Their primary focus was especially on the academic, and religious education of Catholic boys, and the main institution charged with this mission was Saint Aloysius College. Despite the many challenges linked to finances and manpower, Jesuits invested their energies and resources in the college for two main goals: enabling Catholic boys to access government positions and improve their financial status, and, thanks to a quality institution, seeking to win the Brahmans’ appreciation of the Christian religion. The thesis shows how the college’s genesis can be located both within the British Indian development of a missionary schools’ system, and within the expansion of the global network of Jesuit schools and colleges and its search for a distinctive Jesuit identity. In fact, in the aftermath of the Restoration of the Society of Jesus, government authorities, such as in British India, strictly regulated schools’ curricula and structures. At Saint Aloysius, therefore, the Jesuits decided to emphasize extracurricular activities, both through devotional life, expressed in common prayers and liturgies, as well as other activities inherited from their centuries long pedagogical tradition, such as the prize awarding system, games, sports, theater plays.

While some of the documents used here, especially from the Historical Archives of the Jesuit Euro-Mediterranean Province (AEMSI), have never been used before, many aspects of the mission still remain to be explored. For instance, no comprehensive history of the Jesuit presence in Mangalore has been written using archival sources. Furthermore, Indian perspectives on the impact and consequences of the Jesuit presence in South Canara have only started to be evaluated.[166] And interaction, competition, and reciprocal influence between Catholic and Protestant colleges and missionaries in nineteenth century India remain unexplored territories.

Notes:

[1] This article has been written as a dissertation for the degree of Master of Studies (MSt) in Theology–Ecclesiastical History, at the Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Oxford. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my parents and family for their encouragement throughout this journey, to Rev. Dr. Brian Mac Cuarta, S.J., for his guidance and supervision, and to the community, staff, and friends of Campion Hall for their friendship and support.

[2] Lettere Edificanti della Provincia Veneta [henceforth LE] (1888), 112.

[3] Catalogus Defunctorum 1814–1970, ed. Rufo Medizábal, S.J. (Curia Gen. S.I., 1972).

[4] Presidencies in British India were “provinces under direct control and supervision of, early on, the East India Company, and after 1857, the British government. The three key presidencies in India were the Madras Presidency, Bengal Presidency, and the Bombay Presidency;” “Presidencies in British India,” Britannica, accessed 7 March 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/presidencies-in-British-India-Bombay-Madras-and-Bengal.

[5] Letters and Notices (henceforth LN), vol. 13 (1880), 315.

[6] Memorials Submitted to the Holy See and the Late Right Rev. Dr. Clement Bonnand, Visitor Apostolic of India by the Catholic Community of Canara (Madras, 1874), 5–6.

[7] LE (1899), 144.

[8] LN, vol. 19 (1887), 563.

[9] The concern Propaganda Fide raised officially was not linked initially to educational matters, but rather the shortage of priests and the consequent lack of appropriate spiritual assistance for the local Catholics; ARSI Karn.1001, Missio Mangalorense, I, I, 2, September 6, 1877.

[10] See correspondence with the Visitor General of India, dated May 15, 1860, and a letter addressed to Pope Pius IX dated July 13, 1868 in Memorials Submitted to the Holy See, 5–20, 43. On different Protestant societies in India and on some conversions of Catholics see Denis Fernandes, “Jesuit Initiatives in Higher Education in Karnataka and Kerala,” in Jesuit Initiatives in Indian Higher Education, ed. Joan Dias, Savio Abreu, and Keith D’Souza (Mumbai, 2021), 114.

[11] Memorials Submitted to the Holy See, 3–4.

[12] Rudolf Fischer, Die Basler Missionindustrie in Indien 1850-1913 (Zurich, 1978), 7.

[13] William J. Danker, Profit for the Lord: Economic Activities in Moravian Missions and the Basel Mission Trading Company (Wipf& Stock Publishers, 1971), 83ff.

[14] Parinitha Shetty, “Missionary Pedagogy and Christianisation of the Heathens: The Educational Institutions Introduced by the Basel Mission in Mangalore,” The Indian Economic & Social History Review 45, no.4 (December 2008): 512, https://doi.org/10.1177/001946460804500402.

[15] The Fortieth Report of the Basel German Evangelical Missionary Society (Mangalore, 1880), 77.

[16] Thomas Anchukandam, The First Synod of Pondicherry 1844 (Bangalore, 1994), 20.

[17] Fernandes, “Jesuit Initiatives,” 115.

[18] Vishanz Pinto, “Canara Catholics in the Bombay Presidency,” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 66 (2005): 787–88.