Research Article

Circa Missiones: Jesuit Understandings of Mission through the Centuries

Introduction and Keynotes

Jesuit Missions and Multilateral “Accommodations” in the Early Modern World

Russel, Camilla. “Jesuit Missions and Multilateral “Accommodations” in the Early Modern World.” In “Circa Missiones: Jesuit Understandings of Mission through the Centuries (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Lisbon, Portugal, June 12–14, 2023),” ed. Alessandro Corsi, Claudio Ferlan and Francisco Malta Romeiras, special issue, International Symposia on Jesuit Studies 3, no. 1 (2025): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2023.02.

Jesuits in the early modern period regularly worked in territories that were beyond the jurisdictions of European empires and therefore operated as guests of local rulers and their populations. In these contexts, the practice of accommodatio became a useful tool for the mission work of the Society of Jesus. Jesuits—although not all and not in every circumstance—were among the method’s most prominent practitioners in the Catholic missions of the early modern period.

The missionary method—which I will call here “Jesuit accommodatio”—famously gave rise to broad interactions with host societies in the religious, cultural, scientific, and linguistic spheres; it also did so in the political, social, and economic domains (see fig. 1). Consequently, it provides insights into early modern worlds, in turn explaining the sustained scholarly interest in it. Ines G. Županov, Nicolas Standaert, Markus Friedrich, Stefania Tutino, and Hélène Vu Thanh[1]—to name just some in Jesuit historical studies—have engaged with and critiqued Jesuit accommodatio in terms of the opportunities and problems it presents for contemporary scholars working in Jesuit, global, and mission research fields.

Building on these studies, this contribution seeks to demonstrate that in the early modern period Jesuit accommodatio generated such a high degree of contact, information, and mutual influence between those involved that, despite its many limitations, it represents an unusual and valuable documentary access-point to territories beyond Europe where Europeans operated but did not rule. While Jesuit accommodatio was relatively limited in application, reception, and duration—it had neither an explicitly codified status nor was it treated as a Society-wide mission policy, and it was defeated ultimately in its early modern form—the present study shows that its historical significance lies elsewhere. The missionary method depended to an unusually large extent (with respect to other methods of the time) on the Jesuits’ hosts for it to work, producing a fascinating multidirectional dynamic that offers rich insights into early modern contact history.

Fig. 1. Matteo Ricci and Michele Ruggieri (attrib.), Portuguese–Chinese dictionary (sixteenth century), Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu (ARSI), Jap. Sin. I 198, fol. 34r. Reproduced with permission.

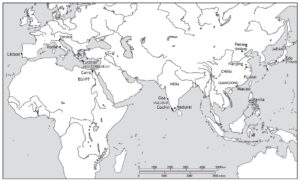

The first part of the essay explores the historical background and foundations of Jesuit accommodatio, as well as recent historiographical treatments of the subject and frameworks for its use in historical research. The second part showcases a range of examples, types, and applications of the practice in missionary contexts beyond Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, concentrating on the Eastern Mediterranean and Asia, where Jesuit missions were funded and operated through the patronage and travel routes of the Portuguese Estado da Índia. It does this through a series of case studies using the correspondence of mainly Italian Jesuits who departed Lisbon for mission work in Egypt, India, China, and Macao (see map).

Map 1. Main Places Mentioned in the Article

The analysis draws on unpublished and published letters, preserved, respectively, in ARSI and in the publications of Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu, Monumenta series. Taken together, the correspondence will be used to illustrate how Jesuit accommodatio worked in practice and how the recorded flow-on effects of the practice offer distinct and promising lines of research for exploring how Europeans were accommodated—or not—by host societies and how Jesuits accounted for and responded to this experience in the early modern world.

Accommodatio: From Ancient Roots to Early Jesuit Foundations

Tutino observes that accommodatio means adapting the “true” to the “real”: in the Christian context, the term refers to the process of adapting Christianity to the cultural and social realities in which missionaries found themselves (in some cases through dissimulation and disguise), with the aim of securing conversion.[2] From its beginnings, the practice was both extremely practical—Christianity had to adapt itself to local circumstances, languages, and mores if it were to expand and take hold in non-Christian terrain—and at the same time theologically grounded.[3]

According to this view, in accomodatio, a term originating in Judeo-Christian traditions that used the idea of divine accommodation as the basis for adapting universal principles to particular circumstances, God’s voice is adapted to the various forms of human language in order to be apprehended by them.[4] Within Christianity, adaptation was especially relevant in the context of Christ’s evangelical directive to “go and make disciples of all nations.”[5]

Paul the Apostle provided a model for how to put the directive into practice:

To the Jews I became like a Jew to win over Jews […]. To those outside the law I became like one outside the law—though I am not outside God’s law but with-in the law of Christ—to win over those outside the law. To the weak I became weak, to win over the weak. I have become all things to all, to save at least some.

While this described the means, the ultimate goal of course was Christian conversion and salvation, as Paul wrote: “All this I do for the sake of the gospel, so that I too may have a share in it.”[6]

The Pauline call to adaptation—outlined in 1 Corinthians—as one of several scriptural calls to the practice, finds many Ignatian echoes. For example, the theme of accommodation has a pronounced presence in the Spiritual Exercises (begun 1521; first published 1548).[7] The document written by Ignatius for use in an extended course of meditation within a retreat setting notably stipulated that the Exercises were to be adapted to the “disposition of the persons who desire to make them, that is, to their age, education and ability.”[8] The idea was that the retreat was an exchange, not a lesson; it was dialogic and interactive, rather than mono-directional and prescriptive:

In order that both the giver and receiver of the Spiritual Exercises may be of greater help and benefit to each other, it should be presupposed that every good Christian ought to be more eager to put a good interpretation on a neighbour’s statement than to condemn it […]; one should correct the person with love.[9]

The ground thus was set for a distinctive flexibility and open inter-relational style in Jesuit spiritual work. In a similar, but also much broader sense, in the Exercises the entire world was set in an optimistic frame: “I will consider how God dwells in creatures; in the elements, giving them existence; in the plants, giving them life; in the animals, giving them sensation; in human beings, giving them intelligence; and finally, how in this way he also dwells in myself [my emphasis].”[10] Such an all-encompassing and positive view of God’s creation and the people in it—including oneself—created threads for thinking about and approaching travel to distant lands and living among their different peoples.

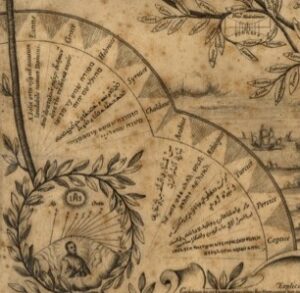

The Jesuit practice of adaptation to one’s environment was woven into the fabric of the Constitutions (completed 1552; printed 1558–59).[11] Flexibility was a recurrent theme in this foundational text, which, while unusually detailed with innumerable directives about almost every conceivable aspect of life as a Jesuit, left open the prospect for many “situational provisos.”[12] This included the theme of adaptation. One of the key tools for this practice was learning languages for the work of conversion: in addition to the usual theology, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, the Constitutions stipulated that in the universities of the Society, “there may be teachers of Chaldaic, Arabic, and Indian, where these are necessary or useful […] with attention given to the diversities of place and reasons which may move us to teach them [my emphasis]”[13] (see fig. 2).

Also, in terms of dress, famously, the Constitutions advised that Jesuits were to choose clothing that suited the local norms and circumstances of those in the local area in an equivalent state of life to them, according “to the usage of the region where one is living.”[14] Immediate environments and local practices thus were to determine many aspects of Jesuit formation, learning, and life, and not the other way around.

Fig. 2. Ignatian Tree, or “Horoscopium catholicum.” Athanasius Kircher, Ars magna luciset umbrae (2nd ed., 1671): detail, depicting languages spoken in lands where Jesuits were present, including Hebrew, Syriac, Chaldaic, and Arabic. Reproduced with the kind permission of ARSI.

Jesuit Accommodatio in Time, Terminologies, and Historiographies

With its foundations thus established—anchored in scriptures, with an embedded fixedness in the Ignatian spiritual worldview, and transmitted through the Society’s early documents—Jesuit accommodatio warrants careful investigation in time, place, and practice within the Society of Jesus.[15] While some form of accommodatio is al-ways present to some extent in conversionary contexts as part of the work of bringing people from the outside to the inside of Christianity,[16] it manifested more decisively in some historical contexts than in others. At its most visible, it was employed by Jesuits traveling east and operating without the cover of the conquistador empires, where missionaries did not have the upper hand and instead were in the vast melting pot of the early modern eastern trade routes or else new arrivals held in suspicion or indifference by introverted or supremely confident kingdoms. In all these settings, Jesuits were minorities in every sense.[17]

In several of these lands, Jesuits identified local populations with the so-called “gentiles” of the early Christian era. The pagans of the Classical world converted as a result of St. Paul’s directive to adapt the Christian message to the audience and liberate the Gospel message from its Jewish roots, laws, and customs to encompass all peoples in all corners of the world.[18]

Among Jesuits, accommodatio was by no means universally adopted: it was hardly applied at all in several Jesuit operations, and in some cases the opposite strategy was practiced. This is because the method was only one possible component of the Jesuit “way of proceeding,” depending on need—as St. Paul had taught—and it was not the ultimate aim, which was “to help souls”: in the mission context, this constituted above all conversion to the Catholic faith.[19] The flexibility noted above as a hallmark of the Jesuit Constitutions was balanced in parts by insistence on uniformity and obedience—to one’s superiors, the pope, and the teachings of the Catholic Church.[20] With this end in mind, Jesuits had to be prepared to be strict or pliable depending on the circumstances and what was requested of them.

Members of the Society of Jesus thus often participated in enforcing Catholicism, for example in some of its works with the Goa Inquisition, in Northern and Eastern Europe’s Counter-Reformations, and in its role in several key events of the Galileo affair.[21] Indeed, often, Jesuits operated on opposite sides, in conflict with each other: with their collective spiritual and operational eye trained on bringing about “the greater glory of God,” sometimes they adapted to their environment and interlocutors and sometimes they did not, according to their judgment of the circumstances and people involved and following the directions of the Constitutions, which advised an agile—not standardized—response.[22]

Since it was by no means uniformly or universally practiced in the Society, Jesuit accommodatio presents an array of interpretive challenges and historiographical uncertainties. As scholars have pointed out, it was not even a term readily used by Jesuits themselves in the early modern period: instead, il modo soave—“the sweet method”—and, before that, the Ignatian concept “our way of proceeding” were used by some to describe practices later associated with the term accommodatio. Tellingly, in the Malabar mission context, according to Antony Mecherry, S.J., the term accomodarse was used for the first time—in 1580—not to describe Jesuit mission practice but as a criticism of the Thomas Christians for not adapting their form of Christianity to that of the “Latin” Catholic Church.[23] According to Županov, it was the Malabar rites controversies that engulfed the mission in the eighteenth century that marked the starting point for the term accommodatio to identify the Jesuit mission approach there.[24]

In a still later context, Friedrich has explored how the nineteenth century saw the most widespread use of the term and argues that its acquired meaning in the historiography of the early modern period is more closely connected to the Jesuit realities, rhetoric, and policies of the modern period than it is to early modern Jesuit mission contexts, thus anachronistically skewing scholarly interpretations of it in the historiography of early Jesuit operations.[25] By contrast, for Vu Thanh, “accommodation is unmistakably a characteristic of the [early modern] Asian missions.” Crucially, she qualifies this reading by identifying accommodatio less as a formal method than as a rather haphazard practice, which emerged from “fragile, tentative, and often embattled experiments”: it was the focus of “constant struggles over [its] meaning, scope, and adequacy.” And as Vu Thanh notes, its limits were apparent for all to see: “Founded as it was on deep mutual cultural misunderstandings, the policy could only result in failure.”[26] Indeed, by the mid-eighteenth century the Roman hierarchy of the Catholic Church had rejected Jesuit accommodatio, while widespread conversion had not taken root where it had been practiced.

It was thus as much a tenuous practice as it remains an unstable concept. This is reflected in current terminology that ranges from “religious accommodation” (Županov) to “Jesuit accommodation” (Mecherry), to the “rhetorical or accommodating style” (John W. O’Malley).[27] Here, the term Jesuit accommodatio is used to delineate both the ancient and innovative characteristics of the practice that saw its first and most sustained use since the beginning of Christianity in the Jesuit mission context of the early modern period.[28]

While the method did not succeed in the long term—Europeans had no power in the lands where it was practiced and consequently failed to make Christianity a wide-spread religion in those lands—Jesuit accommodatio activated a series of dynamics whereby Jesuits were being shaped by their environment and local populations were accommodating them.[29] This was an unusual dynamic to say the least in the history of European recorded experiences in non-European lands and among those lands’ peoples. How this worked in practice—and the textual traces it left behind in the Jesuit correspondence from the period—is the subject of the case studies presented in the second part of this study.

Diplomacy and Accommodatio in the Eastern Mediterranean

Some of the earliest examples of Jesuit cultural experimentation took place not among “gentiles” but among Christians in the Eastern Mediterranean whom Jesuits, under papal directive, sought to bring into union with the Catholic Church. One such Jesuit was Giovanni Battista Eliano (formally Elia Romano [1530–89]), grandson of the celebrated Hebrew grammarian and lexicographer Elia Levita. Eliano was a Jewish convert to Catholicism who entered the Society of Jesus in 1551—the same year as his conversion, at the age of twenty-one.[30] Toward the end of his life, Eliano explained in his autobiographical narrative about his conversion what it was like to move from one world into another—and the back-and-forth experiences and impulses it brought while the conversion process was taking place in Venice, just after he had decided to become Christian:

Given that in September there were many Jewish festivals, there were times when I was tempted to leave and go to the synagogue and throw myself at the feet of all the Jews to ask their pardon for the scandal that I had caused them in not having come to the synagogue […]. At the time, I found myself in great confusion, seeing that I was in a state of being neither Jew nor Christian.[31]

During his life as a Jesuit, Eliano made several missions in the Mediterranean region for the Society and at the request of the pope. For example, Eliano traveled back to Egypt—where some of his family lived—with a special mission to the Coptic Church. Here, separation and integration were always vividly present, with Eliano perfectly placed to describe the complex dynamics of the melting-pot environments into which Jesuits entered (see map). Staying with his Jesuit companions in Cairo in 1561 as guests of the Venetian consul, Eliano described to Superior General Diego Laínez (1512–65, in office 1558–65) how their host had offered to procure a separate building for the Jesuits, with its own chapel for saying Mass, moving from its “current location [which is] too public because it is almost always full of infidels—as much Turks, as Moors and Jews.”[32]

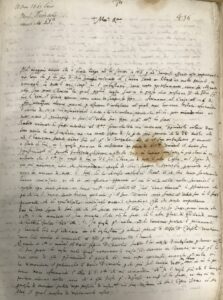

While the Jesuit presence in the above example appears to have caused the separation of Christian ritual from the quotidian activities of non-Christian bystanders, it also highlights the diplomatic frame for the Jesuits’ mission, as guests of the consul in their capacity as papal envoys. They practiced the arts of diplomacy too. In one such case, the Jesuit mission leader, Cristóbal Rodríguez, wrote a report to the papal secretary in Rome, demonstrating the essentially diplomatic frame within which the Jesuits traveled, conveying “the great charity and good will that His Holiness [the pope] has toward him [Patriarch Gabriel VII (r.1525–68)] and his clergy, and all the other Copts,” adding too the pope’s purpose: his desire for “unity of all with the Roman Catholic Church” (see fig. 3).[33] Diplomacy clearly was one of the tools used by Jesuits to enter the non-Catholic sphere in their search for adhesion to the Catholic Church, a forerunner, in some senses, to later Jesuit cultural adaptation beyond the Christian world and on a larger scale.

The diplomatic frame within which some Jesuit works took place provides important clues about the link between European diplomacy—which was developed in the very same Renaissance culture in which the Society was forged—and the cultural adaptation developed by Jesuits in the non-Christian lands of the “gentiles”—the key method for the practice of accommodatio.

Fig. 3. Letter of Cristóbal Rodríguez to Monsignor Antonio Floribello, Cairo, December 10, 1561. ARSI, Epp. Nn. 86, fols. 106r and 107r. Reproduced with permission.

First Steps of Jesuit Accommodatio in India

In India, from the 1580s, it was also in the Christian communities that another key chapter in Jesuit accommodatio unfolded, among members of the ancient Syro-Malabar Church whose followers are sometimes called “Thomas Christians” after the Apostle Thomas, traditionally identified as the source of Christian conversion in India. Led by the Catalan Jesuit Francisco Ros (1559–1624), the pioneering feature of the practice adopted in Malabar, according to Mecherry, was that, after initially adopting a severe approach to local differences from Latin Christianity, Ros gradually came to view local “social structures and customs in a mission context as facilitating agents and not obstacles in the way of mission.”[34] These early steps in accommodatio (and its limits) among the Christian populations of India were closely observed in person by the Jesuit visitor to the East Indies Alessandro Valignano (1539–1606) and by Matteo Ricci (1552–1610), before developing their own versions of the practice in Japan and China respectively (see map). For this reason, Mecherry identifies the innovations developed by Ros among the Malabar Christians as crucial “testing grounds” for Jesuit accommodatio.[35] The practice’s application in India also set a pattern for resistance to it that was ever-present in its history. For his part, Ros defended his mission approach against fellow-Catholic missionaries, whom he called Romanizers, arguing that “it is impossible to force the [Thomas] Christians to do the things that they are not ready for.”[36] Instead, Ros, while remaining uncompromising on what he saw as the theological errors of his Christian interlocutors (and initially engaging in censorship of them), over time developed a system of engagement with the local Christians through trial and error, whereby he adapted Catholic worship in all but the essentials to local forms and practices, thus seeking to distinguish form from essence and opening the path to adaptation in the former and insisting on adherence to Rome in the latter.

A further important shift in the history of Jesuit accommodatio came once more from India, this time among non-Christians. In the first decade of the seventeenth century, Roberto de Nobili (1577–1656) drew from Ros’s model of working among the Thomas Christians and applied similar approaches among the high castes of Madurai (from 1606).[37] Again it fell to his mentor Ros, by then archbishop of Angamaly-Cranganore (in the Malabar region), under whose jurisdiction de Nobili worked, to explain and defend the approach in a letter to Superior General Claudio Acquaviva (1543–1615, in office 1581–1615):

Now it has pleased God our Lord to make use of Father de Nobili, so that by adopting the dress of the country, by learning their different languages, by con-forming to their way of eating and to many of their customs, which entail no offence to God, he might win the esteem and affection of the people, and that the proud Badages [military elites in Madurai] and self-conceited Brahmins, who look down on everybody, might be brought under the yoke of Our Lord Jesus Christ crucified.[38]

Cultural adaptation, as is evident here, was possible without being accompanied by esteem for the other. The work of Ros and de Nobili in India produced a new approach, where—as Županov has noted—Jesuits distinguished politics from religion and Christianity from being European. While not entirely an innovation, it was unusual for Europeans at the time and also deemed necessary for the Jesuits to be accepted. In practice, Jesuits like de Nobili depended on extensive collaboration—indeed accommodation—from locals, who advised him how to dress, behave, and appear: for Županov, the “tipping point” of de Nobili’s adaptations eventually being ruled unacceptable by the Catholic Church was in the body not in words for, while “accommodation always starts with semantics,” “by taking up the role of a Brahmin [de Nobili] crossed the red line […] when [he] came to literally embody a Brahmin sannyāsi.” Through his body, language, behavior, and dress, de Nobili effectively became like the Brahmins that accommodated him deep into their own norms and practices, remaining a striking figure in visual representations of him long after his death (see fig. 4). At the same time, this level of adaptation was not tolerated, as the outcomes of the Malabar rites controversies attested by the middle of the eighteenth century. The limits of Jesuit accommodatio had been set.[39]

Fig. 4. Print from Alfred Hany, “P. Robertus de Nobilibus Romanus

Soc: Iesu […],” Galerie illustreé de la Compagnie de Jésus […] 6 (1893),

pl. 1. Reproduced with the kind permission of ARSI.

Jesuit Accommodatio among the “Gentiles”: China and Macao

Just over two decades after Eliano’s journey to Egypt in the 1560s, and in the same decade as Ros practiced Jesuit accommodatio among the Thomas Christians of India, the Italian Jesuit Michele Ruggieri (1543–1607) was in faraway China. On February 7, 1583, shortly after his arrival on the Chinese mainland, in Zhaoqing (Guangdong), Ruggieri wrote a report to Superior General Acquaviva (see map). On several occasions in his long letter, Ruggieri mentions the kind of work he expected to undertake there, in particular one of the most important pillars of accommodatio, learning the language of the Chinese “to explain our concepts, and our way of proceeding.”[40] Jesuit accommodatio was identified as the best way to do this, and the result in China, famously, was a substantial level of adaptation to the Chinese context.

Of course, unlike the Christian peoples of the Mediterranean and India, for the Jesuits the Chinese were “gentiles” who did not belong to any Christian faith. They also had the upper hand. Shortly before Ruggieri wrote his letter, fellow-Jesuit Francesco Pasio (1551–1612) explained in his report to Acquaviva—sent from Macao on December 25, 1582—how Ruggieri was to gain entry to China through a “very important lord and powerful [figure] in China.” This lord “sent to have Michele Ruggieri called [to China] and has given hope that he wants to give the [Jesuits] a house with a temple containing his idols where father [Ruggieri] may stay and learn the language […], demonstrating a great deal of love toward the said father.” The reason, apparently, was that “he found out that the father had a clock that told the hours, which is a very valued thing among them [the Chinese].”[41] While the Jesuits here are seen to be constantly looking for opportunities to enter into contact with their hosts, Pasio observes the agency and pragmatism of the Chinese mainland’s future hosts. For Pasio, the offer from China must be viewed with circumspection “because ordinarily the [Chinese] lie and make no moves unless it is for their own interests.”[42] Such observations—albeit written from the Jesuit perspective—reveal accommodation and adaptation as practices used by both sides, for a variety of motivations.

The balance, of course, was entirely unequal in terms of power—and was the operational reason for the Jesuit practice of accommodatio. The Jesuits’ presence in China as well as in Portuguese Macao depended on the Chinese. As Pasio wrote from Macao in 1596, over a decade after Ruggieri’s early letter from China, quoted above: “Macao [is] a small city without any territory and it can be unmade anytime that China wants it”[43] (see map). The Jesuits adapted their mission practice to this reality by adopting accommodatio.

Fig. 5. Manuscript Map: “Descriptio geographica Sinici, Coraisi et Japonici regni” (seventeenth century): detail, ARSI, Grandi Formati, cassetto 14. Reproduced with permission.

The Jesuits understood that their ability to stay on the Chinese mainland also depended on them demonstrating their usefulness. As Ruggieri explained to Acquaviva in his 1583 letter about his Chinese hosts, beyond language, he identified that cultural sophistication, knowledge across many fields, and ability in numerous spheres of human activity were important for Jesuits to gain a foothold in China. He wrote: “It is important for these lords of China, given that they are of great ability and art in government […], that we [ Jesuits] are erudite and that we know how to do other things of ability” (see fig. 5).[44] The very practice of accommodatio, which allowed the Jesuits into China and to operate there and in Portuguese Macao, provided a window onto China’s awesome power and determined the Jesuit missionary approach there. Most of all, it was possible only because the Chinese accommodated the Jesuits and not the other way around.

Conclusion

For Jesuit missionaries, accommodatio was a temporary meeting place afforded to prospective converts on the way to changing one’s very nature through conversion. This represents a limit of accommodatio for scholars seeking information beyond the religious objectives of the practice. It is also an opportunity: in the recorded practice of Jesuit accommodatio in the early modern missions, a window opens through these sources onto the non-Jesuit interlocutors of these reports, if in a limited way, and as accommodators of their Jesuit guests.

I have shown how the ancient genealogy of accommodatio, its Ignatian foundations in the Society of Jesus, and formative conditions for its development in Jesuit mission works, especially in the East, provided ideal conditions for mutual accommodation between different, previously separated groups. While accommodatio was not explicitly prescribed for Jesuit mission practice nor universally practiced, it did definitely exist in the early modern Society. It was also groundbreaking in applying an ancient Christian method in the “new” global reality in which Jesuit mission work was forged, with the strongest concentration of the practice being applied among Italian Jesuits working in Asia.[45] Cultural adaptation was its central pillar. It also generated vast textual and other material records about first-time meetings and then prolonged contact between groups. While filtered through the Jesuit gaze, and put into Jesuit words and therefore one-sided, the documents reveal that in order for it to work, Jesuit accommodatio depended on local accommodation of the Jesuit visitors.

This is one of the values of Jesuit accommodatio for scholars. The practice created what Županov, borrowing from Homi K. Bhabha,[46] has called “a third space,” and what Standaert has called “spaces of encounter.” In these spaces, Jesuits in non-European settings in the early modern world partially adapted themselves and their messages to local environments. Jesuit accommodatio as a mission practice further created the conditions for a wider exchange of multilateral accommodations, which were not solely religious in their features and that mutually influenced all parties involved. As Standaert observes: “The outcomes of the exchange, a text, image, conversion, social network, community [are all possible features] of the interaction.” For this reason, Jesuit accommodatio potentially provides important opportunities for understanding early modern worlds and their different voices—alongside sources not produced by Jesuits.[47]

While providing an entry-point to early modern perspectives, Jesuit accommodatio is even more valuable when viewed not only as a Jesuit missionary method but also through its ripple effects. These included shared practices and mutual influences that traveled multi-directionally. Jesuit accommodatio only worked effectively in such a frame of meeting. In the early modern context, the dynamics produced by the practice had wider consequences and longer genealogies than the conversionary method itself. It is in this broader frame that the historical significance of Jesuit accommodatio comes into view—generating a multilateral exchange that entailed action both on the Jesuits’ part and on the part of the people who were accommodating them—with both sides engaged in what we might conceptualize as “accommodating Jesuits.”

Notes:

[1] Ines G. Županov, “Religious Accommodation: Historicity, Teleology, Expansion,” in Pathways through Early Modern Christianities, ed. Andrea Badea, Bruno Boute, and Birgit Emich (Cologne: Böhlau, 2023), 125–53, providing an important survey of the topic; Nicolas Standaert, “Matteo Ricci and the Chinese: Spaces of Encounter between the Self and the Other,” in Lezioni cinesi: Storia, filosofia, e antropologia della Cina, ed. Alessandro Dell’Orto and Hongtao Zhao (Rome: Urbaniana University Press, 2017), 73–100, with a helpful treatment of specific questions raised in this contribution; Markus Friedrich, The Jesuits: A History, trans. John Noël Dillon (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2022), provides an important overview, chapter 4, 427–574; Stefania Tutino, “Jesuit Accommodation, Dissimulation, Mental Reservation,” and Hélène Vu Thanh, “The Jesuits in Asia under the Portuguese Padroado: India, China, and Japan (Sixteenth to Seventeenth Centuries),” in The Oxford Handbook of the Jesuits, ed. Ines G. Županov (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 216–40, 400–26, respectively providing useful definitions and regional nuance for exploring the complex history of Jesuit accommodatio.

[2] Tutino, “Jesuit Accommodation,” 218–23. As Vu Thanh notes, Jacques Gernet in 1982 established a new interpretive path by identifying early modern accommodation practiced by Jesuits as “a futile if not hypocritical effort to adapt to societies they ultimately understood very little about”: “Jesuits in Asia,” 402.

[3] Markus Friedrich, “Accommodation: A Twentieth-Century Theological Idea and Its Role in the Historiography of Catholic Missions,” Historical Interactions of Religious Cultures 1, no. 1 (2024): 146–70, here 150–51, noting that scholars often mistake the theological roots of accommodation for historical roots.

[4] Županov, “Religious Accommodation,” 127.

[5] Matt. 28:18–20.

[6] 1 Cor. 9:20–23.

[7] The modern published edition is in Monumenta Ignatiana: Exercitia spiritualia S. Ignatii de Loyola et eorum directoria, ed. José Calveras and Cándido de Dalmases, rev. ed., Monumenta Historica Societatis Iesu (hereafter MHSI) 100 (Rome: Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu [hereafter IHSI], 1969), 1:140–417. English quotations are from Ignatius of Loyola, The Spiritual Exercises and Selected Works, ed. George E. Ganss (New York: Paulist Press, 1991), 113–214 (hereafter identified as Sp. Ex., with standard identifying paragraphs in square brackets). The theme of accommodation—expressed in dialogic and relational forms—in the Spiritual Exercises and elsewhere in Jesuit foundational documents, correspondence, and Jesuit practice more broadly is explored in Camilla Russell, Being a Jesuit in Renaissance Italy: Biographical Writing in the Early Global Age (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2022).

[8] Sp. Ex. [18]. This point is discussed, for example, in Moshe Sluhovsky, “St. Ignatius Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises and Their Contribution to Modern Introspective Subjectivity,” Catholic Historical Review 99, no. 4 (2013): 649–74, here 659–61.

[9] Sp. Ex. [22].

[10] Sp. Ex. [235].

[11] The published modern edition is in Monumenta Ignatiana: Sancti Ignatii de Loyola Constitutiones Societatis Jesu […], 3 vols. (Rome: IHSI, 1934–38). Quotations are from a modern English-language edition, The Constitutions of the Society of Jesus: Translated, with an Introduction and a Commentary, ed. and trans. George E. Ganss (St. Louis, MO: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 1970), hereafter as Const., followed by the relevant paragraph in square brackets. For an analysis of the relationship between accommodatio and the Jesuit Constitutions—as well as the Spiritual Exercises—as expressions of Jesuit adaptability and within a broader historical frame beyond Jesuit history, see Jaska Kainulainen, “Accommodatio in the Jesuit Constitutions,” in Constitutional Moments: Founding Myths, Charters and Constitutions through History, ed. Xavier Gil (Leiden: Brill, 2024), 144–64.

[12] This borrows and slightly adapts the helpful phrase about Jesuit organization being characterized by “centralization with situational provisos”: Markus Friedrich, “Ignatius’s Governing and Administrating the Society of Jesus,” in A Companion to Ignatius of Loyola: Life, Writing, Spirituality, Influence, ed. Robert A. Maryks (Leiden: Brill, 2014), 123–41, here 133.

[13] Const. [447].

[14] Const. [577].

[15] A useful overview of interpretations, themes, and chronology is in Joan-Pau Rubiés, “The Concept of Cultural Dialogue and the Jesuit Method of Accommodation: Between Idolatry and Civilization,” Archivum historicum Societatis Iesu 74, no. 147 (2005): 237–80, with a helpful discussion of key phases at 244–45. Rubiés argues that, while the cultural dialogue generated by this method was filled with mutual misunderstandings, its contribution to the European intellectual tradition was substantial and needs to be taken into consideration as a significant influence in the Enlightenment.

[16] Županov, “Religious Accommodation,” 141.

[17] For this point in relation to China, see Ronnie Po-chia Hsia, “Imperial China and the Christian Mission,” in A Companion to Early Modern Catholic Global Missions, ed. Ronnie Po-chia Hsia (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 344–64 (especially 344).

[18] See Russell, Being a Jesuit, 62, with examples, in the same, 105–6, 144.

[19] Russell, Being a Jesuit, 52.

[20] Kainulainen, “Accommodatio in the Jesuit Constitutions,” 145–46.

[21] A helpful example of Jesuits standing on opposite sides of a question—theologically, rhetorically, and methodologically—is the case of two catechisms, one by Peter Canisius (who stressed pietas) and the other by Robert Bellarmine (who emphasized veritas): Bellarmine’s won out as the version behind which the Catholic Church galvanized its push toward uniformity and hegemony. See Thomas Flowers, S.J., The Reform of Christian Doctrine in the Catechisms of Peter Canisius (Leiden: Brill, 2023).

[22] John W. O’Malley, “The Historiography of the Society of Jesus: Where Does It Stand Today?,” in The Je-suits: Cultures, Sciences, and the Arts, 1540–1773, ed. John W. O’Malley et al. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999), 1:3–37, here 24–25. For examples of Jesuit disagreements over accommodatio, see Županov, “Religious Accommodation,” 133.

[23] Antony Mecherry, S.J., Testing Ground for Jesuit Accommodation in Early Modern India: Francisco Ros S.J. in Malabar (16th–17th Centuries) (Rome: IHSI, 2019), xlvii.

[24] Županov (citing Savarimuthu Rajamanickam, S.J.), “Religious Accommodation,” 133.

[25] Friedrich, “Accommodation,” 147–48.

[26] Vu Thanh, “Jesuits in Asia,” 416, 403, 402 (page numbers listed in the order of author quotations from this chapter).

[27] Županov, “Religious Accommodation”; for Jesuit accommodation used by several scholars, see, for example, Mecherry, Testing Ground for Jesuit Accommodation; for accommodation’s rhetorical accent, see John W. O’Malley, The First Jesuits (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), 15.

[28] Similarly, Kainulainen, “Accommodatio in the Jesuit Constitutions,” 143, prefers the term accommodatio, translated to signify adaptability; by contrast, this analysis enlists the term without translation to emphasize its specifically theological-evangelical nature, while the idea of adaptability here is connected to the application of accommodatio in the cultural and other spheres on the part of all protagonists involved, and not just in the religious sphere from which the term originates.

[29] This line of approach, explored through a Self–Other analytical frame, is in Standaert, “Matteo Ricci and the Chinese”: see especially 82–83.

[30] For biographical overviews, see Dizionario biografico degli italiani (hereafter DBI), 100 vols. (Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia italiana, 1960–2022), vol. 42 (1993) (Cesare Ioly Zorattini); Diccionario histórico de la Compañia de Jesús: Biográfico-temático (hereafter DHCJ), ed. Charles E. O’Neill, S.J. and Joaquín María Domínguez, S.J., 4 vols. (Rome: IHSI, 2001), 2:1233–34 (Charles Libois).

[31] Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu (ARSI), Hist. Soc. 176 (“Vocationes Illustres I”), fols. 119–45, published in José C. Sola, “El p. Juan Bautista Eliano: Un documento autobiografico inedito,” Archivum historicum Societatis Iesu 4, no. 8 (1935): 291–321. Quotations are drawn from this published transcription; translations are mine, unless otherwise stated. “Et perché in settembre vi sono molte feste de Giudei, alle volte mi veniva tentatione di partirmi et andare alla sinagoga, et buttarmi a piedi di tutti i Giudei per dimandargli perdono dello scandolo datogli in non essere venuto alla sinagoga”; “All’hora io mi trovavo in gran confusione, vedendomi in uno stato, che non ero né Giudeo, né Christiano” (Sola, “El p. Juan Baptista Eliano,” 301–2). These themes of multiple, conflicting, and unstable identities are a key focus of Robert Clines, A Jewish Jesuit in the Eastern Mediterranean: Early Modern Conversion, Mission, and the Construction of Identity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

[32] Giovanni Battista Eliano/Romano (1530–89) to Diego Laínez, Cairo, November 12, 1561: “Una casetta che pagarà […] [e] far una capella per dir messsa, essendo che qui no l’hanno, se non sopra una tavola, che si dice in casa del consol’ in loco tropo publico, per che quasi sempre è piena d’infideli, tanto di Turchi, Mori come di Judei.” ARSI Epp. Nn. 86, fol. 211r. The letter is reproduced in Monumenta Proximi-Orientis II Égypte (1547–1563), ed. Charles Libois, S.J. (Rome: IHSI, 1993), 94 (subsequent references to archival sources, where possible, are followed by the corresponding published reference).

[33] Cristóbal Rodríguez to Monsignor Antonio Floribello, Cairo, December 10, 1561: “La gran charità et amorevolezza che tiene a lui et suo Clero et tutti li altri Copti […] procurando insieme la unione di tutti li suoi con la Chiesa cattolica romana.” ARSI Epp. Nn. 86, fol. 106r/Monumenta Proximi-Orientis II, 115.

[34] Mecherry, Testing Ground for Jesuit Accommodation, 373.

[35] Mecherry, Testing Ground for Jesuit Accommodation, xlviii and chapter 1 (1–85).

[36] From ARSI, Goa-Mal. 14, fol. 357r, quoted and translated in Mecherry, Testing Ground for Jesuit Accommodation, 413.

[37] For a biographical overview, see Matteo Sanfilippo, “De Nobili, Roberto,” DBI 38 (1990).

[38] Francisco Ros to Claudio Acquaviva, July 4, 1613, Malabar (from Jesuit Madurai Province Archives, Shenbaganur, “Letters and Documents on the Syrian Christians,” 3:40), quoted and translated in Mecherry, Testing Ground for Jesuit Accommodation, 367.

[39] Županov, “Religious Accommodation,” 144.

[40] Michele Ruggieri to Claudio Acquaviva, February 7, 1583, Zhaoqing (Guangdong), “per explicare nostri concetti, e il modo de procedere.” ARSI, Jap. Sin. 9 I, fols. 140v.

[41] Francesco Pasio to Claudio Acquaviva, December 25, 1582, Macao, “molto principale e potente nella Cina […] ha mandato chiamare il Padre Michele Rogerio e dà speranza di volergli dare una casa con un tempio deli suoi idoli dove possa il padre stare e imparare la lingua […] e mostrando molto amore al detto Padre […] e massime adesso che seppe che il Padre haveva un orologio che dava le ore che he cosa molto pregiata fra di loro.” ARSI, Jap. Sin. 9 I, “soli,” fol. 112r.

[42] Francesco Pasio to Claudio Acquaviva, Macao, December 25, 1582, “far poco fondamento perché ordinariamente mentono e non si moveno se non per li suoi interessi.” ARSI, Jap. Sin. 9 I, “soli,” fol. 112r.

[43] Francesco Pasio to Claudio Acquaviva, January 30, 1596, Macao, “Amacao, Cità picola senza teritorio nessuno et posta a essere disfata ogni volta che li Cina vorano.” ARSI, Jap. Sin. 12 II, “soli,” fol. 353r.

[44] Michele Ruggieri to Claudio Acquaviva, February 7, 1583, Zhaoqing (Guangdong): “È ben per questi signori della Cina essendo di grande ingegno e arte nel governo […] che siamo dotti, e sappiamo fare altre cose d’ingegno.” ARSI, Jap. Sin. 9 I, 140r.

[45] The features, reasons, and documentary evidence for this are analyzed in Camilla Russell, “Becoming ‘Indians’: The Jesuit Missionary Path from Italy to Asia,” Renaissance and Reformation/Renaissance et Réforme 43, no. 1 (2020): 9–50, here 12–19.

[46] Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 2004).

[47] Županov, “Religious Accommodation,” 146, citing Homi Bhabha’s “third space” terminology and identification of contexts “in which Christianity could exist without European customs and as part of a plural Christian world”; Standaert, “Matteo Ricci and the Chinese,” 100: “The interaction […] causes the partners to readjust, rethink and reformulate ideas.”

- Title: Jesuit Missions and Multilateral “Accommodations” in the Early Modern World

- Author: Camilla Russel

Article Type: Research Article - DOI: 10.51238/ISJS.2023.02

Language: English - Pages: 1–17

- Keywords: global Catholicism; Jesuit mission methods; Eastern Mediterranean; India; China

- Volume: 3

- Issue: 1, special issue

- Publication Date: 30 September 2025

Last Updated: 01 December 2025 - Publisher: Institute of Jesuit Sources

- E-ISSN: 2766-0644

- ISBN: 978-1-947617-35-3

APA

Russell, C. (2025). Jesuit missions and multilateral “accommodations” in the early modern world. In A. Corsi, C. Ferlan, & F. Malta Romeiras (Eds.), Circa missiones: Jesuit understandings of mission through the centuries (Proceedings of the symposium held at Lisbon, Portugal, June 12–14, 2023) [Special issue]. International Symposia on Jesuit Studies, 3(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2023.02

CMOS

Russel, Camilla. “Jesuit Missions and Multilateral “Accommodations” in the Early Modern World.” In “Circa Missiones: Jesuit Understandings of Mission through the Centuries (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Lisbon, Portugal, June 12–14, 2023),” ed. Alessandro Corsi, Claudio Ferlan and Francisco Malta Romeiras, special issue, International Symposia on Jesuit Studies 3, no. 1 (2025): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2023.02.

MLA

Russell, Camilla. “Jesuit Missions and Multilateral ‘Accommodations’ in the Early Modern World.” Circa Missiones: Jesuit Understandings of Mission through the Centuries (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Lisbon, Portugal, June 12–14, 2023), edited by Alessandro Corsi, Claudio Ferlan, and Francisco Malta Romeiras, special issue of International Symposia on Jesuit Studies, vol. 3, no. 1, 2025, pp. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2023.02.

Turabian

Russell, Camilla. “Jesuit Missions and Multilateral ‘Accommodations’ in the Early Modern World.” In “Circa Missiones: Jesuit Understandings of Mission through the Centuries (Proceedings of the Symposium held at Lisbon, Portugal, June 12–14, 2023),” ed. Alessandro Corsi, Claudio Ferlan, and Francisco Malta Romeiras, special issue, International Symposia on Jesuit Studies 3, no. 1 (2025): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.51238/ISJS.2023.02.

© Institute of Jesuit Sources, Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, All Rights Reserved