Research Article

Special Section: Circa Missiones. Jesuit Understandings of Mission through the Centuries

Inner Mission: Mission Landscape of the Provincia Austriae around 1650

Kádár, Zsófia. “Inner Mission: Mission Landscape of the Provincia Austriae around 1650.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., 1, no. 2 (2025): 335–52. https://doi.org/10.51238/5BfZ3t4.

The Austrian Jesuit Province (1563–1773) operated within the geopolitical complexities of Ottoman-occupied Hungary, sustaining Catholic communities and engaging with Protestant, Orthodox, and Muslim populations. This study examines the mid-17th-century Jesuit missionary network, analyzing personnel, mobile and stable missions, and their broader impact. Using Jesuit catalogues and reports, it reconstructs the role of missions within the province’s institutional framework and explores how frontier experiences influenced Jesuits seeking missions further afield. By situating these efforts within broader Catholic missionary strategies, the study highlights the adaptability of Jesuit institutions in contested religious landscapes and their long-term impact on pastoral and educational work.

Keywords:

Jesuit missions, Ottoman-Habsburg relation, Austrian Jesuits, Counter-Reformation, missionary strategies

Introduction

From the 1651 annual report of the Austrian Jesuit Province:

Hungary, Transylvania, and Turkey may open up these Indias rich in heavenly treasures for us, brothers and fathers chosen by God! Certainly, whatever harvest can be hoped for anywhere, whether among the barbarous peoples of Brasil and Virginia, or on the farthest shores of the East, is easily attainable here in the homeland fields on every occasion. If, indeed, the love of Christ impels us to endure the difficulties or the struggling, if we are touched by compassion for the salvation of others, here is our Japan, here is our India! It is therefore in the power of each one of us, if we do not lack the spirit, to become a martyr. But how great is the wish of martyrdom anywhere: there is a place where there is a spirit, there is a battlefield where there is a struggle, there is a warfare where there is a trial, there is death where there is victory. In the end, this conquest of his own self wins by death the laurel of martyrdom.[1]

The author of the report calls the eastern and southeastern parts of the province, that is, the Kingdom of Hungary, a mission territory for a good reason. His statement is remarkable even if we realize that, as in the genre of the Jesuit annual reports, we are dealing here with a topos. Namely, by the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Ottoman conquest had left only the western (also including the southwestern Slavonian and Croatian territories), northern, and northeastern parts of the medieval kingdom (including present-day Slovakia) under Christian (i.e., Habsburg) rule. At the eastern end of the medieval kingdom, the Principality of Transylvania became an internal autonomous but Ottoman vassal “state.” The central third of the kingdom, including the medieval royal seat of Buda and the archbishopric seat of Esztergom, became the borderland of the Ottoman Empire.[2] The institutional crisis of the Catholic Church was exacerbated by the rapid spread of the Reformation: it is estimated that 70–90 percent of the country professed Protestant teachings at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Out of the previously existing religious orders, apart from a few Pauline monasteries, only the Franciscan friary network survived, and these friaries were also concentrated in a few towns.[3]

The Austrian Jesuit Province became independent shortly after the foundation of the Viennese College in 1563. The Polish-Lithuanian houses were separated in 1573, and somewhat later, in 1623, the Bohemian-Moravian domiciles were also separated as a distinct province.[4] Afterwards the Provincia Austriae included Lower, Upper and Inner Austria among the hereditary provinces of the Habsburgs, as well as the countries of the Hungarian Crown, including the Croatian-Slavonic Kingdom and Transylvania.[5] The pastoral care of the remaining Catholic communities in Ottoman Hungary and the Balkans was a matter of interest for various actors from the end of the sixteenth century. On the one hand, the Hungarian prelates: The Habsburg rulers, while preserving their right of supreme ecclesiastic patronage, continuously appointed bishops to head the “conquered” Hungarian dioceses, but they could only send their vicars—some of them Jesuit priests—to the Ottoman/occupied territory. On the other hand, the observant Franciscan order, which tried to bring the former Hungarian (after 1541, Ottoman) territories under the jurisdiction of their Bosnian Province. And finally, the Society of Jesus, which, in accordance with the political and administrative dependencies, was interested on behalf of three Jesuit provinces. First, Dalmatia was part of the Venetian Jesuit Province as part of the Venetian Republic; second, the independent Republic of Dubrovnik was part of the Roman Jesuit Province; and third, most of the Kingdom of Croatia and Slavonia as well as the whole medieval Kingdom of Hungary was part of the Austrian Province.[6]

The following analysis is a snapshot of the Jesuit missionary organization in the borderlands of the Ottoman Empire and Christian Europe in the more “peaceful” period before the Great Turkish War (1683–99) in the mid-seventeenth century. Unfortunately, the historiographies of the successor states of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, since the beginning of the twentieth century, have been thinking in national contexts.[7] In the attempt to go beyond this attitude, in my essay I consider the entire Jesuit Province as the framework of analysis.[8] And in that I heavily rely on two outstanding Jesuit historians, László Lukács and LászlóSzilas. Lukács published the annual personal catalogues of the Austrian Jesuit Province in eleven volumes, and compiled a biographical lexicon of the members of the province in three volumes.[9] Szilas produced a comprehensive analysis of the status of the province before its suppression (personnel, institutions).[10] In relation to the mission organization in Hungary and the Balkans, I also have to mention the outstanding work of Antal Molnár, who has summarized in a pioneering volume the history of the Catholic mission institutions in Ottoman Hungary and the neighboring Balkan territories between 1572 and 1647, including the efforts of the Holy See and the Franciscan and Jesuit orders.[11] Later, he devoted several volumes to the mission organization of special regions and towns, and published a volume of studies on Catholicism in the seventeenth-century Balkans.[12]

My sources are mainly the Jesuit records themselves: annual personal catalogues of the province (published by Lukács), the annual letters (litterae annuae),[13] triennial catalogues (mainly catalogi functionum from the so-called third catalogues of 1649),[14] and some letters from the Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu, from the Indipetae series, requesting “pagan” missions from the Austrian Province.

The Missionary Network of the Province c. 1655

Although the western and eastern regions of the province were part of the same institutional system, the radically different political, legal, financial, social, and confessional conditions led to significant differences between the regions. The institutional network was not a static, fixed system but a dynamic one, always adapting to the circumstances of the moment. It was exactly the lowest parts of the institutional hierarchy, the missions and residences, which were the most variable elements. Their position in the mid-seventeenth century is interesting because it anticipates the later Jesuit institutional development after the reconquest of the Ottoman-occupied territories of the Hungarian Kingdom.

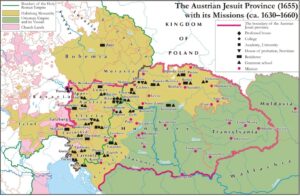

Figure 1. The Austrian Jesuit Province (1655) with its Missions (c. 1630–60). Source: Concept by Zsófia Kádár; design by Béla Nagy.[15]

Figure 1 shows that the western half of the Jesuit province fell within the Austrian hereditary provinces, where the Counter-Reformation, the Catholic Revival, and the development of the Jesuit college network preceded similar developments in the Kingdom of Hungary by decades.[16] The upper part of Table 1 shows that the western half of the Jesuit Province contained the sole professed house in Vienna as well as nine large colleges with related universities, academies or Jesuit novitiates, and tertianships or repetition courses. In addition, there were five “simple” colleges with complete eight-level grammar schools.[17] In the eastern half of the province, in the divided territory of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary, there were three larger colleges. Trnava was notable for its university and the large number of Jesuit members living there, while Zagreb had an academy and Trenčín had a newly founded novitiate. Each of the additional four colleges maintained highly frequented grammar schools. Thus, the western half of the province had a much denser college network and consequently a much larger number of Jesuits: three-quarters of the total membership of the province lived in these “western” houses.

However, if we focus on the residences and missions belonging to the colleges, we find an opposite pattern. There were only six residences in the western half of the province, and all of them were originally founded as administrative centers for Jesuit estates. In the eastern half of the province, on the other hand, there were many more and very different residences and missions, which I group into five categories according to their functions (Categories a–e in the table).

Group a corresponds to the estate centers already mentioned, but in this part of the province there were only two of them: Trnava College was maintained by the estates of the former Premonstratensian monastery of Turóc, whose administrative center was Kláštor pod Znievom; Zagreb College included estates in the Put area.

| Table 1. Domiciles and missions of the Austrian Jesuit Province, 1655 | ||||||

| Austrian hereditary provinces | ||||||

| Type | Professed house/college | Staff | Type | Dependent residence | Staff | |

| Vienna (domus professa) | 58 | — | — | |||

| A | Graz (univ.) | 132 | a | Millstatt | 6 | |

| A | Vienna (univ.) | 99 | a | St. Bernhard-Frauenhofen | 6 | |

| A | Vienna, St. Anna-Haus (nov.) | 88 | a | Žireč [Schurz] | 6 | |

| A | Leoben (repetentes) | 65 | — | — | ||

| A | Judenburg (domus tertiae prob.) | 39 | — | — | — | |

| A | Passau (acad.) | 35 | a | Traunkirchen | 6 | |

| A | Klagenfurt (acad.) | 26 | a | Eberndorf | 3 | |

| A | Ljubljana [Laibach] (acad.) | 25 | a | Pleterje [Plettriach] | 5 | |

| A | Gorizia [Görz] (acad.) | 22 | — | — | ||

| B | Linz | 27 | — | — | ||

| B | Steyr | 20 | — | — | ||

| B | Trieste | 15 | — | — | ||

| B | Krems | 14 | — | — | ||

| B | Rijeka [St. Veit, Fiume] | 13 | — | — | ||

| Kingdom of Hungary | ||||||

| Type | College | Staff | Type | Dependent residence/mission | Staff | |

| A | Trnava [Tyrnau, Nagyszombat] (univ.) | 67 | a | Kláštor pod Znievom [Turóc] | 2 | |

| b | Banská Bystrica [Besztercebánya] | 7 | ||||

| c | Gyöngyös (res., gymn.) | 5 | ||||

| c | Cluj [Kolozsvár] | 4 | ||||

| c | Alba Iulia [Gyulafehérvár] | 2 | ||||

| c | Odorheiu Secuiesc [Székelyudvarhely] | 3 | ||||

| A | Zagreb [Agram, Zágráb] (acad.) | 23 | b | Varaždin [Varasd] | 11 | |

| a | Ptuj [Pettau] | 3 | ||||

| c | Karlovac [Karlstadt, Károlyváros] | 2 | ||||

| A | Trenčín [Trencsén] (nov.) | 11 | e | Illésházy | ||

| B | Pressburg [Bratislava] | 19 | e | Archbishop’s mission | ||

| B | Sopron [Ödenburg] | 17 | e | Esterházy, Nádasdy | ||

| B | Győr [Raab] | 16 | b | Komárno [Komárom] | 6 | |

| c | Veszprém | 2 | ||||

| d | Pécs | 2 | ||||

| d | Andocs | 1 | ||||

| B | Užhorod [Ungwar, Ungvár] | 11 | b | Košice [Kaschau, Kassa] | 9 | |

| b | Spišské Podhradie [Szepesváralja] | 10 | ||||

| c | Carei [Nagykároly] | 4 | ||||

| e | Rákóczi, Károlyi | |||||

| Abbreviations | ||||||

| Types of colleges | ||||||

| A | College with university, academy or Jesuit house of probation | |||||

| B | College with grammar school | |||||

| Types of residences and missions | ||||||

| a | Administrative center of landed property | |||||

| b | “Initiated college” with grammar school | |||||

| c | Residence or stable mission | |||||

| d | Wandering mission | |||||

| e | Mission to aristocratic family (on family estate). Members counted as staff of the mother college. Italic indicates family, not town, name. | |||||

Group b consists of those residences that were collegii inchoati[18]: Banská Bytrica, Varašdin, Košice, and Spišske Podhradie indeed developed into colleges. Nevertheless, in the case of Komárno the unexpected death of the potential founder, General Michael Adolf von Althan, resulted in a failing change in status; thus it never became a real college. The five residences all had important grammar schools, but typically only with two to three classes and one or two teachers.

Group c, residences and stable missions, were domiciles with two to five members, for which the goal of becoming a college was in 1655 not realistic at all. They were typically not located in the Habsburg (Catholic) territories, but either in Transylvania or on the border of the Ottoman Empire,—that is, the missionary territory of the Jesuit Province. Among them, Cluj in Transylvania and Gyöngyös on the edge of the Ottoman Empire had important grammar schools; thus, in fact, in these minor houses the whole spectrum of traditional Jesuit apostolic areas—education, pastoral care, and mission—was also present. Group d included Pécs and Andocs, where classic wandering missions were to be found. They were primarily responsible for the pastoral care of the scattered Catholic communities in the Ottoman-Hungarian territories. The living conditions of the Jesuits, often alone or at most in pairs, were similar to those of their fellows sent on “barbarian” or overseas missions. But there was an important difference: they knew the local conditions, culture, and languages, and were mostly able to understand the changing administrative, military, and denominational circumstances.

In Group e, I mention the special missions that, at the request of aristocratic families, were active on family estates. They were somewhat similar to the Jesuits’ “court missions,” yet they had a more distinctive missionary character. These Jesuits had to lead the Re-Catholicization of Protestant estates if requested by the family heads. In 1655, we are still in the more peaceful period of what Hungarian research, following Katalin Péter, calls the “missionary or converting seigneurial Counter-Reformation,” in which the use of violent methods and even military force became typical only from the 1670s onward.[19]

If these stable and wandering missions were largely based in Christian territories, why are they associated with “pagan” missions? After all, the Jesuit report quoted at the beginning of this essay clearly refers to all three parts of the Kingdom of Hungary—Hungary, Transylvania, and Turcia—as “our India and our Japan.” While total cultural division was absent, what mostly connected the two types of mission in the eyes of the Jesuits was the objective of conversion of the Protestant, Greek Orthodox, and Islamic populations and, even more, the possibility of martyrdom. Around 1650, the memory of two Jesuits, István Pongrácz and Melchior Grodziecki, who were murdered in 1619 in Košice by soldiers of Gábor Bethlen, the prince of Transylvania, was still vivid.

Melchior Grodziecki and István Pongrácz arrived in the contemporary center of Upper Hungary, in Košice, as Slovak and Hungarian preachers and missionaries. The canon of Esztergom, Márk Kőrösi, was also working in the town on behalf of his Archbishop Péter Pázmány. The town suffered much in the warfare between the Habsburgs, namely a local Catholic aristocrat, György Drugeth of Homonna, and the protestant Transylvanian prince, Gábor Bethlen. In 1619, when Bethlen’s armies occupied Košice, the three priests were tortured and killed by Calvinist soldiers (hajdúk) in one of the darkest moments of the Hungarian confessional conflicts.[20] The deaths of the martyrs of Košice were notable because they were killed for refusing to convert to Calvinism and so were definitely martyrs. But other “anonymous” Jesuits were also victims of marauding soldiers during this period—for example, Stanislaus Domokos, a Jesuit Scholastic in 1664 in the region of Trenčín, aged only thirty.[21] This murder was another indication that being a Jesuit in Hungary at this time was not an entirely harmless enterprise.

Nevertheless, the Jesuit college network, in the middle of all the difficulties, was in a very intense phase of development in the first half of the seventeenth century. From the 1620s onward, the Jesuits built several “bridgeheads” toward Hungary, establishing, after Trnava (the second, already successful, foundation, in 1616), the domiciles of Pressburg (1626), Győr (1627), and Sopron (1636), which soon grew into important colleges and were joined by highly frequented grammar schools.[22] Győr also played an important role as the administrative center of the Jesuit missions of the borderland and the occupied Hungarian territories. According to the special syllabus missionum of the 1655 provincial catalogue, the missions in the diocese of Veszprém, also in the South Transdanubian region, in Andocs and Pécs, belonged to it.[23]

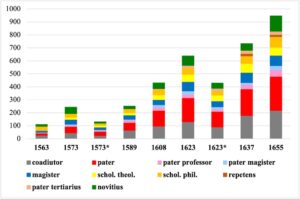

If we follow the development of province personnel up to the same year (1655), the expansion of the institutional system becomes clear: the newly founded colleges and smaller domiciles were increasingly filled with members. Moreover, by the middle of the seventeenth century the proportion of Jesuits of Hungarian origin had begun to grow. Figure 2 shows the distribution of Jesuits by vows and functions as well as the spectacular growth in the number of personnel. All this adds nuance to the traditional interpretation of the Society as a religious order dedicated mainly to education. We can see a very dynamic, uninterrupted increase in numbers: up to 1608 there was an increase of almost 400 percent and after the division of the province in 1623 (into Bohemian and Austrian parts) another 200 percent, with a total of 889 members in 1655. The percentage of members according to function was—except for the first decade—quite stable, with lay brothers representing about 23 percent; novices and students, about 31 percent; grammar schoolteachers, about 13 percent; university professors, about 6 percent; and priests serving in pastoral or leadership positions, about 30 percent.

Figure 2. Development of province personnel (1563–1655): increase in membership by status (vows) and function. Source: Ladislaus Lukács, Catalogi. I used selected years to show the trends.

Living in the “Inner” Missions: Jesuits in Pécs and Gyöngyös

Detailed case studies and microhistorical analyses help us get to know the inner, daily life and the specific world of the Jesuit missions. In the case of Ottoman Hungary, we owe these analyses largely to Antal Molnár. In the following, we can gain insight into the difficulties and achievements of missionary work through the examples of two towns, Pécs and Gyöngyös.

The 1606 Treaty of Zsitvatorok, which ended the fifteen-year so-called Long Turkish War between the Christian (Habsburg) troops and the Ottoman Empire, made it clear to both Vienna and Rome that the border zone and the extent of Ottoman conquest at that time were a long-term reality. This created new conditions for the Catholic missionary organization, with missionaries from several directions: South Slavic Franciscans from Ragusa and Bosnia, supported by Rome, and Jesuits from the Austrian Province, supported by Vienna. Throughout this process, Franciscans and Jesuits of local origin played a key role, as their knowledge of local languages and conditions made it easier for them to get along in territories under Ottoman administration.

Pécs

The mission of Pécs was organized in around 1612, and its aim was to serve the scattered Catholics of Baranya County, who spoke Hungarian and South Slavic (Croatian).[24] Their pastoral care was then provided only with certain priestly duties by entrusted laymen (licentiates) because of the lack of consecrated priests. Among the Jesuits, the role of Gergely Vásárhelyi is remarkable. Vásárhelyi first served as a missionary in the region of Lendava and gained a great reputation as a healer among the Turks. The mission of Pécs held two to three members, had Hungarian superiors, and was attended by Croatian Jesuits, thus maintaining lively relations with Zagreb College as well.

The Society planned to establish a grammar school in Pécs to serve the wider border region, but for various reasons they were forced to modify this plan. Due to the lack of Jesuits, their school had been taught only by secular magisters. As the town was an Ottoman administrative seat (the seat of a sanjak), the position of the mission was not stable enough to improve the school.

Development was also hampered by competition from the local Unitarian school. Therefore, the main task of the mission remained the pastoral care of the small Catholic communities in the countryside. Although the small Pécs school continued to function after the foundation of the Jesuit gymnasium in Gyöngyös, it went through a period of crisis in the 1640s due to the scandalous behavior of a lay teacher: despite having graduated from a Jesuit gymnasium, the schoolmaster, who was drunk and promiscuous, came into contact with the Turks and was circumcised, which gave the local Unitarians (Anti-Trinitarian Protestants) sufficient reasons to mock the school of Pécs.

A typical example of missionary challenges in Ottoman territories is the case of Miklós Blaskovich, Jesuit Superior of Pécs. One morning in 1649, on the authority of the pasha of Kanizsa, the father, with other Christian churchmen, was dragged before the local Ottoman court (divan), accused of having contacts with Hungarian soldiers of the boarder fortresses (hajdúk), which was strictly forbidden by the Turks. The father, who had been a missionary for ten years, cleared himself of the charges with great fortitude, but was later imprisoned by the bey (sancakbeyi) of Pécs and released only on the orders of the aga of Kanizsa. As a result, Christian raids continued to be regular in the border region, which made everyday life difficult for the missionaries and their communities on the Ottoman side.[25]

Although there were recurrent conflicts between Jesuit missionaries and Ottoman officials, and the local Unitarian community in Pécs was strong, the most important achievement of the Jesuit mission was to provide pastoral care for the local Hungarian and Croatian Catholics in the long term, so that Catholic communities in Pécs and in the villages of Baranya County survived until the great Turkish wars.

Gyöngyös

Gyöngyös, with a population of around 8,000, was an important trading center located on the Ottoman-Christian border on the Ottoman side.[26] The local cloister of the Observant Franciscans, with 20 to 22 friars, played an important role in the pastoral care of the market town, which made the Jesuits for a while hesitant concerning their settling there. In the early 1630s, however, a Hungarian Jesuit, György Forró, was the Austrian provincial (1629–34), who, in the spirit of healthy patriotism, supported the Hungarian members in their missionary work in Gyöngyös as well in the remote regions of Hungary. He strengthened the Pécs mission and laid the foundations of the Gyöngyös residence. The support of the bishops of Eger, the enthusiasm of Catholic town leaders, and the positive attitude of the Trnava college rector were also important factors.

The Gyöngyös residence and grammar school were opened in 1634, and had the primary aim of providing a high-quality Catholic secondary education, with a yearly 200 to 300 students in the 1640s.

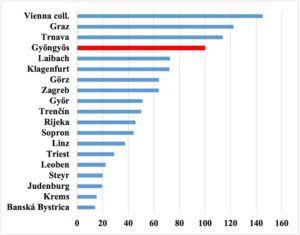

As shown in Figure 3, according to the triennial catalogues of 1649 the Gyöngyös grammar school was comparable to the largest in the province in terms of the number of students per one magister (100). Imagine the burden that the housing of these boys, 300 in total in 1649, meant for the local community given the lack of a boarding house (convictus). In addition, the Catholic town council regularly fell victim to conflicts with Ottoman authorities; for example, renegade Hungarian soldiers tried to abduct their sons from the school and have them circumcised. Moreover, the Jesuits could expect regular reprisals for students arriving in Gyöngyös from Christian settlements in the border region or even from the Pécs mission area, as serfs of the Baranya Ottoman military leaders (sipahis), their seigniorial lords.

Figure 3. Number of students per teacher in selected grammar schools of the Austrian Province, 1649. Source: Catalogus tertius seu rerum Provinciae Austriae anni 1649. Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu Austr. 28, 252–4.

In the midst of such difficulties, the Gyöngyös residence functioned stably. School theatrical performances, Jesuit sermons in front of up to 5,000 believers, “Assumption” and “Agonia Christi” Congregations, and Baroque devotional forms and processions, which were common elsewhere as well, show that the house in Gyöngyös became an important link in the Jesuit institutional system. In fact, there were a good number of Jesuit vocations: before 1700, twenty-two members of the Society came from Gyöngyös.

Instead of a Conclusion: Lessons from Some Indipeta Letters

Naturally, I cannot draw a comprehensive picture of the missions, but I would like to raise one more question concerning the middle third of the seventeenth century. General Claudio Acquaviva, urging the “internal” missions, considered the organization of local apostolates and local missions important,[27] and as we have seen, in the Austrian Province, recognition was gradually achieved from the 1610s onward, when the necessary financial and human conditions were already in place. In any case, how did the “missionary” territories, as internal parts of the Austrian Province, influence sending Jesuits to more distant, “barbarian” missions, even overseas, or retaining them in place? I have a few examples from the Indipeta letters of the province: I focus primarily on letters sent by members who were also active in the “eastern” domiciles (in the Hungarian Kingdom).[28] Among the Austrian, Croatian, Slavic, and Hungarian Jesuits, who requested a mission, Peter Hervay (Croata) in 1626 was sent to Zagreb instead of India, where, unfortunately, he died young.[29] Andreas Mikhez (Austriacus) also asked for a mission twice in vain, and his easternmost place of ministry was in Trnava.[30] Georg Harman (Bohemus, 1641) also was not allowed further than Trnava: he served in large Austrian colleges for most of his life.[31]

Without going into a long list of similar examples, I mention just one successful missionary request from 1655, when Johann Grueber (Austriacus) was sent by his superiors to China and India. He was the first European to cross Tibet and the Himalayas. What is remarkable is that, on his return to the Austrian Province, he did not serve in the populous Western colleges but in Eastern Hungary, in Sárospatak; he also served as field chaplain to imperial troops. After a short break in Trnava and Győr, he served again in the residence of Sárospatak until his death.[32] My last example is Michael Rokochich (Croata), the first Jesuit to address a known Indipeta letter from a Hungarian domicile, Trnava, in 1674. Instead of Constantinople where he had asked to go, he was sent to Pécs, Andocs, Varaždin, and Gyöngyös, long serving as a missionary in the Ottoman areas and at the borders.[33]

The few examples and the relevant volume of the Indipetae letters suggest that until the 1670s, the Jesuit provincials and generals rarely sent members to missionary work outside the Austrian Province. However, the Great Turkish War after 1686 changed conditions completely. In the reoccupied territories, new opportunities opened up for the Catholic Church, including the foundation of Jesuit houses. After the Treaty of Požarevac (1718), however, the Jesuits of the Austrian Province did not go beyond the Habsburgs’ political sphere of influence for missionary purposes. From the beginning of the eighteenth century, the role of the missions was changing. In parallel, the lower segment of the Jesuit institutional system, as it was just described, disappeared.

The different institutional developments of the seventeenth century continued to have an impact until 1773. In the eighteenth century, there were considerably more residences in the eastern, “Hungarian,” area of the Austrian Province than in the western areas, and their function was different. As I have already pointed out, the residences adjacent to the large Jesuit colleges in the Austrian hereditary provinces functioned as administrative centers of estates, and therefore their transformation into colleges was not an option. However, the new residences established in the Kingdom of Hungary from the 1680s onward were of a different nature. In some cases, the former mission centers continued to function as residences, but new ones were being established, although their activities were quite similar to those of the colleges: they almost always had a secondary school (with at least two to three classes), carried out extensive pastoral activities, and served as starting points for missionary journeys. Some of them were on the verge of being developed into colleges in 1773 (e.g., Székesfehérvár). All of this shows that “delayed,” or at least highly different, institutional development in the eighteenth century was still a long-term effect of the Ottoman occupation. The diverse missionary forms of the mid-seventeenth century and later differences between residence types are in themselves vivid evidence of the fact that the institutional network, often portrayed as static, was in fact highly adaptable, flexible, and, despite apparent failures, capable of producing significant results.

Notes:

[1] “Has nobis Indias, patres fratresque a Deo electi, aperit Ungaria, Transylvania, Turcia coelestibus praedivites thesauris. Certe si quid uspiam est sive barbaras inter Brasiliae Virgineaeque gentes seu ad extremas Orientis oras sperandae messis hic domestico in agro usque quaque obvium. Si quod vero etiam pati adversum aut arduum Christi urget amor: si alienae salutis commiseratione tangimur, hic Japon est, hic India nostra. Igitur in cuiusque nostrum potestate iam situm, ne animus desit, martyrem fieri. En quanta undequaque martyriorum seges, ibi locus, ubi animus, ibi arena, ubi aerumna, ibi certamen, ubi experimentum, ibi mors, ubi victoria; hic demum victor sui animus martyrii lauream de morte reportat.” From Litterae annuae Societatis Iesu provinciae Austriae 1651 (Vienna: Austrian National Library Manuscript Collection), Cod. 12048, 34–35. Cf. Antal Molnár, A katolikus egyház a hódolt Dunántúlon [Catholic Church in the Conquered Transdanubia], METEM könyvek 44 (Budapest: METEM, 2003), 64.

[2] Géza Pálffy, Hungary Between Two Empires 1526–1711, trans. David Robert Evans (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2021), esp. 91–99, 199–204.

[3] Dániel Siptár, “Sokszínűség vagy egységesség: Szerzetesség a 17. századi Magyarországon [Multiplicity or Uniformity: Religious Orders in Seventeenth Century Hungary],” in Katolikus egyházi társadalom a Magyar Királyságban a 17. században [Catholic Ecclesiastical Society in the Kingdom of Hungary in the Seventeenth Century], ed. Szabolcs Varga and Lázár Vértesi, Egyháztörténeti Műhely 3 (Pécs: Történészcéh Egyesület and META-Egyesület, 2018), 143–68.

[4] Ladislaus Lukács, ed., Catalogi personarum et officiorum Provinciae Austriae S.I., vols. 1, 2 (Rome: Institutum Historicum S.I., 1978, 1982).

[5] After 1623, the Austrian Jesuit Province retained its integrity, unified central organization, and membership in spite of repeated attempts at division. Lukács, A független magyar jezsuita rendtartomány kérdése és az osztrák abszolutizmus (1649–1773) [The Question of the Independent Hungarian Jesuit Province and Austrian Absolutism (1649–1773)], Adattár 16–18. századi szellemi mozgalmaink történetéhez 25 (Szeged: JATE, 1989).

[6] See the works of Antal Molnár, cited below, and Teodora Shek Brnardić, “From Acceptance to Animosity: Trajectories of Croatian Jesuit Historiography,” in Jesuit Historiography Online (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1163/2468-7723_jho_COM_192535.

[7] A few examples: Bernhard Duhr, Geschichte der Jesuiten in den Ländern deutscher Zunge, vols. 1, 2 (Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder, 1907, 1913), and vol. 3 (München–Regensburg: G. J. Manz, 1921); László Velics, Vázlatok a magyar jezsuiták múltjából [Sketches from the Past of the Hungarian Jesuits] (Budapest: Szent István Társulat, 1912); Miroslav Vanino, Isusovci i hrvatski narod [The Jesuits and the Croatian Nation], vols. 1, 2 (Zagreb: Filozofsko-Teološki Institut Družbe Isusove u Zagrebu, 1969); Emil Krapka and Mikula Vojtech, eds., Dejiny spoločnosti ježišovej na Slovensku [History of the Society of Jesus in Slovakia] (Ontario: Dobrá kniha, 1990).

[8] About the importance of the Jesuit Province as an institutional framework, see Markus Friedrich, Der lange Arm Roms? Globale Verwaltung und Kommunikation im Jesuitenorden 1540–1773 (Frankfurt: Campus Verlag, 2011), 403–29.

[9] Lukács, Catalogi personarum et officiorum Provinciae Austriae S.I., vols. 1–11 (Rome: Institutum Historicum S.I., 1978–95); and Catalogus generalis seu Nomenclator biographicus personarum Provinciae Austriae Societatis Iesu (1551–1773), vols. 1–3 (Rome: Institutum Historicum S.I., 1987–88).

[10] Ladislaus Szilas, “Die österreichische Jesuitenprovinz im Jahre 1773,” Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu 47 (1978), 95–158, 27–349.

[11] Molnár, Katolikus missziók a hódolt Magyarországon (1572–1647) [Catholic Missions in Ottoman Hungary (1572–1647)], Humanizmus ésreformáció 26 (Budapest: Balassi, 2002).

[12] Molnár, Katolikus egyház a hódolt Dunántúlon; Mezőváros és katolicizmus: Katolikus egyház az egri püspökség hódoltsági területein a 17. században [Market Town and Catholicism: Catholic Church in the Conquered Territories of the Bishopric of Eger in the Seventeenth Century], METEM könyvek 49 (Budapest: METEM, 2005); Confessionalization on the Frontier: The Balkan Catholics Between Roman Reform and Ottoman Reality, Interadria, Culture dell’Adriatico 22 (Rome: Viella, 2019).

[13] For the mid-seventeenth century, I used the manuscript collection held in the Austrian National Library in Vienna.

[14] The catalogi functionum was not a regular part of the so-called third catalogues (catalogi tertii seu rerum). The 1649 third catalogue is therefore more detailed than the reports of other typical years.

[15] Figure 1 and Table 1 are based on Lukács, Catalogi personarum, vols. 2, 3, supplemented by extensive research on Jesuit institutional history, mainly with data from the annual reports: Litterae annuae Provinciae Austriae 1631–1660, Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu, Austr. 136, Austrian National Library Manuscript Collection, Cod. 12218–20, 12049–57.

[16] I generally use the current (official) names of the towns. In the case of early-modern multilingual towns, I give language name variants only in the table. In the case of Bratislava, since the name of the city is later, I prefer to use Pressburg, the contemporary German name.

[17] In the Austrian Province, the Jesuit grammar schools represented the school type that had lower, “parva,” classes (or rather “parva” student groups).

[18] For the institutional development of the Jesuit “college,” see Lukács, “De origine collegiorum externorum deque controversiis circa eorum paupertatem obortis (1539–1608),” Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu 29 (1960): 189–245; and vol. 30 (1961): 3–89, esp. vol. 29, 244. Lukács stresses that the “unfinished” colleges were also based on the Constitutions: they were complete but needed improvement.

[19] On the phenomenon of the “missionary or converting seigneurial Counter-Reformation” and the example of the Rákóczi family and Zsófia Báthory, see Katalin Péter, “A jezsuiták működésének első szakasza Sárospatakon [The First Phase of the Jesuits’ Activity in Sárospatak],” in Papok és nemesek: Magyar művelődéstörténeti tanulmányok a reformációval kezdődő másfél évszázadból [Priests and Noblemen: Essays on the Hungarian Cultural History of One-and-a-half Centuries of the Reformation], A Ráday Gyűjtemény tanulmányai 8 (Budapest: Ráday Gyűjtemény, 1995), 186‒99. On the case of the Esterházy family, see István Fazekas, “Adalékok a fraknói grófság és a kismartoni uradalom rekatolizációjához [Contributions to the Re-Catholicization of the County of Fraknó/Forchtenstein and the Manor of Kismarton/Eisenstadt],” in A reform útján: A katolikus megújulás Nyugat-Magyarországon [On the Road to Reform: The Catholic Revival in Western Hungary], A Győri Egyházmegyei Levéltár kiadványai: Források, feldolgozások 20 (Győr: GyEL, 2014), 196–215. On the next, more violent period of Counter-Reformation, see Béla Vilmos Mihalik, Papok, polgárok, konvertiták: Katolikus megújulás az egri egyházmegyében (1670–1699) [Priests, Burghers, Converts: The Catholic Renewal in the Diocese of Eger (1670–1699)], Monumenta Hungariae Historica, Dissertationes (Budapest: MTA BTK TTI, 2017), esp. 152–230.

[20] B. Natoński and K. Drzymała, “M. Grodziecki,” in Diccionario Historico de la Compañía de Jesus. Bibliográfico-temático, vol. 2, ed. Charles E. O’Neill and Joaquín M. Domínguez (Rome: Institutum Historicum S.I.–Universidad Pontificia Comillas, 2001), 1823. Also, Szilas, “Pongrácz, István (Esteban),” in Diccionario Historico [. . .], vol. 4, 3189; Mihalik, “A politika áldozatai—a Magyar Jezsuita Rendtartomány védőszentjei: a kassai vértanúk [The victims of Politics—the Patron Saints of the Hungarian Jesuit Province: the Martyrs of Košice],” in Jezsuiták Magyarországon: A kezdetektől napjainkig [Jesuits in Hungary: from the Beginning to the Present Day], ed. Réka Szokol and Szilárd Szőnyi (Budapest: JTMR–Jezsuita Kiadó, 2021), 128–31; Orsolya Száraz, “A kassai jezsuita mártírok kultusza a 17–18. században [The Cult of the Jesuit Martyrs of Košice in the Seventeenth-Eighteenth Centuries],” in Mártírium és emlékezet: Protestáns és katolikus narratívák a 15–19. században [Martyrdom and Memory: Protestant and Catholic Narratives in the Fifteenth–Nineteenth Centuries], ed. Gergely Tamás Fazakas, Mihály Imre, and Száraz, Loci Memoriae Hungaricae 3 (Debrecen: Debrecen University Press, 2015), 254–73. The martyrs were beatified in 1904 and canonized in 1995. The two Jesuits became patron saints of the newly founded Hungarian Jesuit Province in 1909.

[21] Annuae Litterae Provinciae Austriae 1664, Austrian National Library Manuscript Collection, Cod. 12061, 32.

[22] About the history of these three colleges, see Zsófia Kádár, Jezsuiták Nyugat-Magyarországon a 17. században: A pozsonyi, győri és soproni kollégiumok [Jesuits in Western Hungary in the Seventeenth Century: The Colleges of Pressburg, Győr and Sopron], Monumenta Hungariae Historica: Dissertationes (Budapest: BTK TTI, 2020).

[23] Lukács, Catalogi personarum, vol. 3, 442. The catalogue also mentions the Catholic market town of Jászberény, which was also in the Ottoman-Hungarian territory, but an organized Jesuit mission could not be established there. Gyöngyös played a key role in this region. About Jászberény, see Molnár, Mezőváros és katolicizmus, 66–74.

[24] When describing the two missions, I rely on Molnár’s detailed analyses. About Pécs: Katolikus egyház a hódolt Dunántúlon, 11–119.

[25] Molnár, Katolikus egyház a hódolt Dunántúlon, 105.

[26] About the Jesuit mission of Gyöngyös in the seventeenth century, see Molnár, Mezőváros és katolicizmus, esp. 86–94, 136–50, 171–83.

[27] See for example Philippe Lécrivain, “Les missions de l’intérieur, un ministère privilégié de la Compagnie de Jésus, sous Ignace de Loyola et Claudio Aquaviva,” Studia Missionalia 60 (2011): 195–214; and Molnár, Katolikus missziók, 153–54.

[28] Of course, there were some successful missionary requests from the Austrian Province in the first half of the seventeenth century as well, but these were the exception rather than the rule. One case: Mihalik, “Von Krems nach Goa: Ein vergessener Bericht des Kremser Jesuiten Andreas Xavier Koffler SJ (um 1603–51),” in Die Jesuiten in Krems—Die Ankunft eines neuen Ordens in einer protestantischen Stadt im Jahr 1616, ed. Herbert Karner et al., Studien und Forschungen aus dem Niederösterreichischen Institut für Landeskunde 71 (St. Pölten: Verlag Niederösterreichisches Institut für Landeskunde, 2018), 192–200.

[29] Lukács, ed., Catalogi personarum, vol. 2, 619. Also, Indipetae 24, 35–37 (1626).

[30] Lukács, Catalogi personarum, vol. 2, 677. Also, Indipetae 24, 60, 82 (1636, 1641).

[31] Lukács, Catalogi personarum, vol. 2, 612. Also, Indipetae 24, 87, 89, 92 (1641).

[32] Lukács, Catalogus generalis, vol. 1, 471. Also, Indipetae 24, 196 (1655). His life career is well known; see for example E. Hambye, “Grueber, Johann,” in Diccionario Historico [. . .], vol. 2, 1827; Johann Grueber, Als Kundschafter des Papstes nach China, 1656–1664: Die erste Durchquerung Tibets, ed. Franz Barumann (Stuttgart: Thienemann, 1985).

[33] Lukács, Catalogus generalis, vol. 3, 1396. Also, Indipetae 24, 287 (1650, 1655).

Brnardić, Teodora Shek. “From Acceptance to Animosity: Trajectories of Croatian Jesuit Historiography.” In Jesuit Historiography Online. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1163/2468-7723_jho_COM_192535.

Duhr, Bernhard. Geschichte der Jesuiten in den Ländern deutscher Zunge. Vols. 1, 2. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder, 1907, 1913. Vol. 3. München–Regensburg: G. J. Manz, 1921.

Fazekas, István. “Adalékok a fraknói grófság és a kismartoni uradalom rekatolizációjához [Contributions to the Re-Catholicization of the County of Fraknó/Forchtenstein and the Manor of Kismarton/Eisenstadt].” In A reform útján: A katolikus megújulás Nyugat-Magyarországon, edited by A Győri Egyházmegyei Levéltár, 196–215. Győr: GyEL, 2014.

Friedrich, Markus. Der lange Arm Roms? Globale Verwaltung und Kommunikation im Jesuitenorden 1540–1773. Frankfurt: Campus Verlag, 2011.

Hambye, E. “Grueber, Johann.” In Diccionario Historico de la Compañía de Jesus. Bibliográfico-temático, vol. 2, edited by Charles E. O’Neill and Joaquín M. Domínguez, 1827. Rome: Institutum Historicum S.I.–Universidad Pontificia Comillas, 2001.

Kádár, Zsófia. Jezsuiták Nyugat-Magyarországon a 17. században: A pozsonyi, győri és soproni kollégiumok [Jesuits in Western Hungary in the Seventeenth Century: The Colleges of Pressburg, Győr and Sopron]. Monumenta Hungariae Historica: Dissertationes. Budapest: BTK TTI, 2020.

Krapka, Emil, and Mikula Vojtech, eds. Dejiny spoločnosti ježišovej na Slovensku [History of the Society of Jesus in Slovakia]. Ontario: Dobrá kniha, 1990.

Lécrivain, Philippe. “Les missions de l’intérieur, un ministère privilégié de la Compagnie de Jésus, sous Ignace de Loyola et Claudio Aquaviva.” Studia Missionalia 60 (2011): 195–214.

Lukács, Ladislaus. A független magyar jezsuita rendtartomány kérdése és az osztrák abszolutizmus (1649–1773) [The Question of the Independent Hungarian Jesuit Province and Austrian Absolutism (1649–1773)]. Adattár 16–18. századi szellemi mozgalmaink történetéhez 25. Szeged: JATE, 1989.

Lukács, Ladislaus, ed. Catalogi personarum et officiorum Provinciae Austriae S.I. Vols. 1–11. Rome: Institutum Historicum S.I., 1978–95.

Lukács, Ladislaus. Catalogus generalis seu Nomenclator biographicus personarum Provinciae Austriae Societatis Iesu (1551–1773). Vols. 1–3. Rome: Institutum Historicum S.I., 1987–88.

Lukács, Ladislaus. “De origine collegiorum externorum deque controversiis circa eorum paupertatem obortis (1539–1608).” Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu 29 (1960): 189–245; and vol. 30 (1961): 3–89.

Mihalik, Béla Vilmos. Papok, polgárok, konvertiták: Katolikus megújulás az egri egyházmegyében (1670–1699) [Priests, Burghers, Converts: The Catholic Renewal in the Diocese of Eger (1670–1699)]. Monumenta Hungariae Historica, Dissertationes. Budapest: MTA BTK TTI, 2017.

Mihalik, Béla Vilmos. “Von Krems nach Goa: Ein vergessener Bericht des Kremser Jesuiten Andreas Xavier Koffler SJ (um 1603–51).” In Die Jesuiten in Krems—Die Ankunft eines neuen Ordens in einer protestantischen Stadt im Jahr 1616, edited by Herbert Karner et al., 192–200. Studien und Forschungen aus dem Niederösterreichischen Institut für Landeskunde 71. St. Pölten: Verlag Niederösterreichisches Institut für Landeskunde, 2018.

Molnár, Antal. Katolikus missziók a hódolt Magyarországon (1572–1647) [Catholic Missions in Ottoman Hungary (1572–1647)]. Humanizmus és reformáció 26. Budapest: Balassi, 2002.

Molnár, Antal. Katolikus egyház a hódolt Dunántúlon [Catholic Church in the Conquered Transdanubia]. METEM könyvek 44. Budapest: METEM, 2003.

Molnár, Antal. Mezőváros és katolicizmus: Katolikus egyház az egri püspökség hódoltsági területein a 17. században [Market Town and Catholicism: Catholic Church in the Conquered Territories of the Bishopric of Eger in the Seventeenth Century]. METEM könyvek 49. Budapest: METEM, 2005.

Molnár, Antal. Confessionalization on the Frontier: The Balkan Catholics Between Roman Reform and Ottoman Reality.Interadria, Culture dell’Adriatico 22. Rome: Viella, 2019.

Pálffy, Géza. Hungary Between Two Empires 1526–1711. Translated by David Robert Evans. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2021.

Péter, Katalin. “A jezsuiták működésének első szakasza Sárospatakon [The First Phase of the Jesuits’ Activity in Sárospatak].” In Papok és nemesek: Magyar művelődéstörténeti tanulmányok a reformációval kezdődő másfél évszázadból [Priests and Noblemen: Essays on the Hungarian Cultural History of One-and-a-half Centuries of the Reformation], 186–99. A Ráday Gyűjtemény tanulmányai 8. Budapest: Ráday Gyűjtemény, 1995.

Siptár, Dániel. “Sokszínűség vagy egységesség: Szerzetesség a 17. századi Magyarországon [Multiplicity or Uniformity: Religious Orders in Seventeenth Century Hungary].” In Katolikus egyházi társadalom a Magyar Királyságban a 17. században, edited by Szabolcs Varga and Lázár Vértesi, 143–68. Pécs: Történészcéh Egyesület and META-Egyesület, 2018.

Szilas, Ladislaus. “Die österreichische Jesuitenprovinz im Jahre 1773.” Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu 47 (1978): 95–158, 27–349.

- Article Type: Research Article

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.51238/5BfZ3t4

Language: English - Pages: 335–352

- Keywords: Jesuit missions; Ottoman-Habsburg relation; Austrian Jesuits; Counter-Reformation; missionary strategies

- In: Jesuit Educational Quarterly

- In: 2nd ser., Volume 1, Issue 2

- Received: 24 July 2024

- Accepted: 05 August 2024

- Publication Date: 28 April 2025

Last Updated: 28 April 2025 - Publisher: Institute of Jesuit Sources

- Print ISSN: 2688-3872

- E-ISSN: 2688-3880

APA

Kádár, Z. (2025). Inner mission: Mission landscape of the Provincia Austriae around 1650. Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 1(2), 335–352. https://doi.org/10.51238/5BfZ3t4

CMOS

Kádár, Zsófia. 2025. “Inner Mission: Mission Landscape of the Provincia Austriae around 1650.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., 1, no. 2: 335–352. https://doi.org/10.51238/5BfZ3t4.

MLA

Kádár, Zsófia. “Inner Mission: Mission Landscape of the Provincia Austriae around 1650.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., vol. 1, no. 2, 2025, pp. 335–352. https://doi.org/10.51238/5BfZ3t4.

Turabian

Kádár, Zsófia. 2025. “Inner Mission: Mission Landscape of the Provincia Austriae around 1650.” Jesuit Educational Quarterly, 2nd ser., 1, no. 2: 335–352. https://doi.org/10.51238/5BfZ3t4.

© Institute of Jesuit Sources, Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies, All Rights Reserved